Fifteen million pounds and a hefty slice of architectural vision have transformed the Whitworth from a fusty Victorian art temple into a sumptuous and thoroughly modern gallery. The space inside now channels the visitor from one gallery to another through split levels and along wide, glass-walled extensions. The great barrel-vaulted spaces at the gallery’s core are now flooded with light from the opening up of the building into the park around it. The redevelopment has embraced the landscape surrounding the gallery and thinned the barrier between inside and out.

The transformation is impressive; the sense of space remarkable. The ground floor currently houses a huge assortment of exhibits including, among other things, many fine watercolours, a selection of portraits, Richard Forster’s hyper-realistic drawings and a display with the oddly punctuated title Art_Textiles, which includes all manner of surprising and entertaining work, from Do Ho Suh’s cotton-embedded-in-paper drawings to warrior garb from Mali. Diverse and extensive, the Whitworth is a gallery to dip in and out of rather than trawl around in penitent servitude to a guidebook.

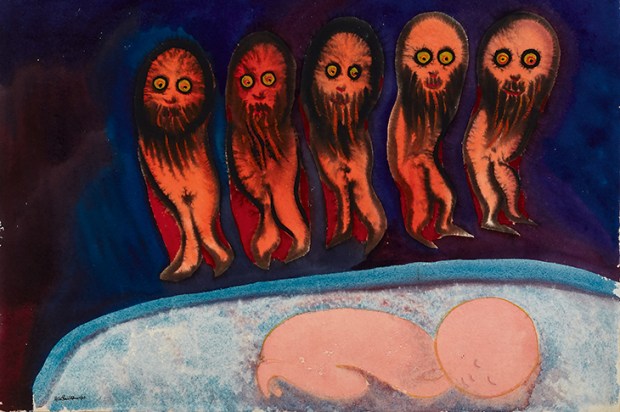

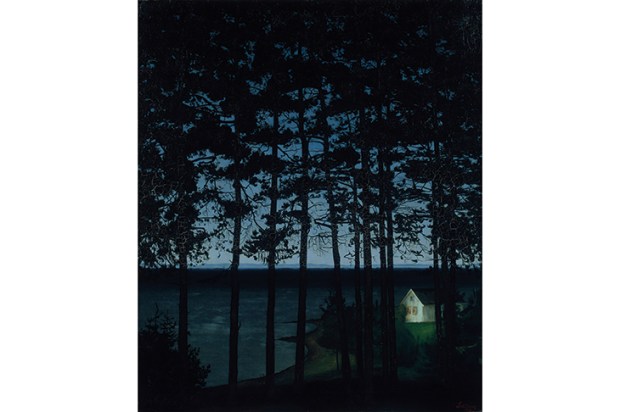

Upstairs, in a little space beside an extravagant installation by Bedwyr Williams, is an understated exhibition of abstract landscapes drawn from the gallery’s own collection. It is one of the smaller displays in the current programme but a welcome one. While the absolutist abstraction of Rothko or Pollock continues to hold sway in the market and in the minds of curators and public alike, the kind of painting exhibited here has fallen from fashion in recent years.

This work, which is all British and dating from the 1950s and ’60s, is painting that treads the edges of abstraction and figuration. Informed by reality, in this case by landscape, it is resonant stuff that allows the viewer to recognise and interpret elements. It is approachable abstraction. The work on display is mostly painting but also includes some sculptural and textile pieces.

Two large hanging textiles by William Scott stand out. One is ‘Skaill’, a tapestry made by Edinburgh Weavers from a design by Scott that was painted to scale with gouache and wax resist. The resulting work is a subtle mass of broken textured forms that hint at rock and edgelands. The work corresponds with its neighbour, ‘Skara Brae’, a length of screenprinted cotton also designed by Scott. This piece, printed in the colours of rock and lichen, speaks clearly of the sunken, stone-lined features of the ancient dwellings of Skara Brae in Orkney. It is an abstraction only until the viewer recognises the source of inspiration.

Scott himself was wary of the abstract label. ‘I am an abstract artist in the sense that I abstract,’ he said, before adding, ‘I cannot be called non-figurative while I am still interested in the modern magic of space, primitive sex forms, the sensual and the erotic, disconcerting contours, the things of life.’

While Scott was specific in acknowledging the sources of his inspiration, Roger Hilton consciously attempted to distance the viewer from his. With work titled merely according to the date on which it was made, the viewer is unguided; abandoned to his own devices. This is no bad thing, for the joy of abstract art is that it relies upon collaboration between artwork and viewer. With no narrative available, and precious little in the way of tangible motifs, the viewer must rely on instinct and feeling alone. The successful abstract will evoke an emotional response in the way that the best music does. Both surpass verbal description, communicating instead on a more fundamental emotional or even spiritual plane.

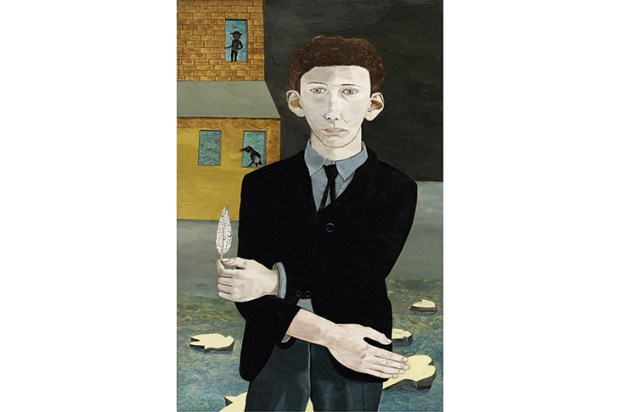

The viewer can bring what they like to Roger Hilton’s work but the reductive titling technique will still lead them in a certain direction. So here we see ‘March 1961’, a loose, scrawly gathering of shapes in blacks, browns and ochres that imply a horizon, punctured in the lower half, or foreground, by a thick blob of white. If that’s not the late winter remains of snow on a rutted landscape then I don’t know what is.

Bryan Wynter’s ‘Earth’s Riches’, a tumbling cascade of brushwork and muted colour is yet more distanced from the figurative. Like a deconstructed, soft-stroke Léger, there is something systematic and almost mechanical in the piece. The colour is that of autumn but shot through with water and rustled by wind. It is a rhythmic painting full of movement and elemental energy.

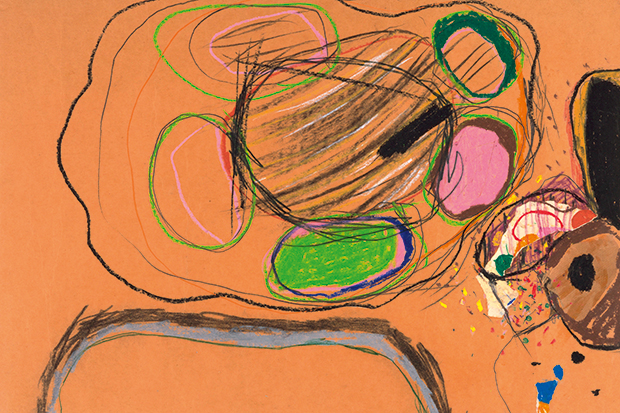

Gillian Ayres, now 85 and still working, is represented by two contrasting early pieces. ‘Reef’ is a long thin painting that carries the viewer with the swell of the sea into a foamy cloud of white, while ‘Untitled’ is a mixed-media drawing. While ‘Reef’ is an obvious study of ocean, the untitled piece, an accumulation of circles, dots, dashes and flat plains of colour, is as far removed from the literal landscape as anything in this show. It sings out loud, however, and the careful balance of composition, which crowds towards the right and uses empty space as a tool in itself, whirls the viewer around in an exuberant vortex of suggested form. The marks are alive with the energy of the infant, informed by the acuity of the observer.

Two spare and delicate Victor Pasmore screenprints that play on the tension of spaces between pulsating forms are a pleasure to see but the one small Peter Lanyon piece on display underplays both his contribution to the genre and his presence in the Whitworth collection. There are many more abstract landscapes hidden away in that 55,000-strong collection and it is tempting to imagine the rewards of a more ambitious and comprehensive exhibition. This little amuse-bouche should whet everyone’s appetite.

The post Approachable abstraction appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in