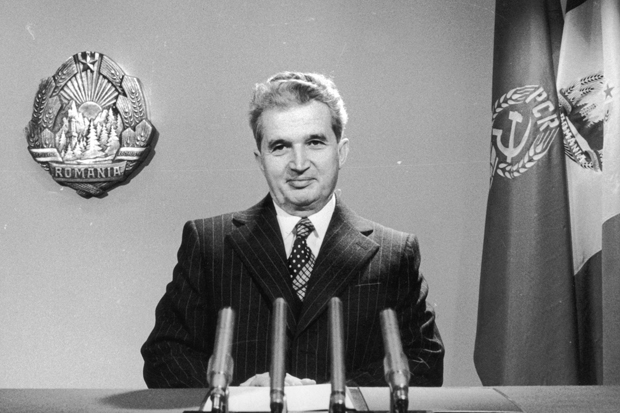

What was it like, asks Jay Nordlinger, to have Mao as your father, or Pol Pot, or Papa Doc? The answer is that while all happy families are alike, the children of monsters are unhappy in their own way. Some dictatorial offspring are fairly normal while others are psychos. Nicu Ceausescu, son of the rulers of Romania, was from the age of 14 a figure of ‘comic-book evil’ whose hobbies included raping women.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £15.99 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in