There’s a hard, hard mood out there among the public and I don’t think our newspapers get it at all. Could it be that the general populace are now more cynical than their journalists?

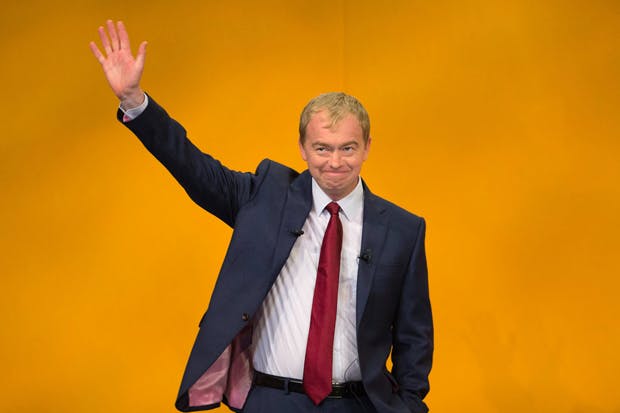

At Tim Farron’s closing speech to his Liberal Democrat conference in Bournemouth last week, I sat through nearly an hour of one of the biggest cartloads of sanctimonious tosh it’s been my fate to endure in decades. And who do you suppose was lapping this up as avidly as any misty-eyed Lib Dem conference-goer? The hardened hacks, the sketchwriters, analysts and reporters. The press are old-fashioned: they love this emotional stuff. But the 21st-century public have been immunised against it.

‘No,’ I inwardly groaned, ‘not Tim’s single mother upbringing again’ — but on we ground through a string of decidedly first-world problems caused by his parents’ decision to separate.

‘No,’ I sighed, ‘not — please not — Cathy Come Home’ (Ken Loach’s half-century-old film about a very different Britain) — but on he squelched, all but wiping away a tear as he confessed how that film had moved him as a boy. J.D. Salinger’s character Holden Caulfield, in Catcher in the Rye, has delivered the last word on people who weep in the cinema: ‘You take somebody who cries their goddamn eyes out over phony stuff in the movies, and nine times out of ten they’re mean bastards at heart.’

In a winking, sniggering, handkerchief-to-the-eye speech he contrived to insinuate that he and his party’s welfare policies arise from the fact that Lib Dems like him care, whereas politicians in other parties don’t. It’s all a matter of how much you care. That two citizens might disagree in good faith about how best to help the poor was not admitted. All you need is love. I wasn’t buying that, and I know that millions of my perfectly nice fellow Britons don’t buy it. But about a thousand Lib Dem enthusiasts were buying it — and almost all reports in the next morning’s papers concurred: not only had the speech moved the hall, it had moved journalists present too.

Come on, guys — don’t you remember Tony Blair peddling this sort of nonsense (though more deftly) at Labour conferences all through the 1990s? It won’t work any more. People today know that welfare policy is a difficult area. Farron’s was a truly 20th-century performance: a sort of Ken Loach tribute band.

I have come to the conclusion that the press are a softer touch than our readers. In one corner of a hall-full of Liberal Democrats last week you had a handful of journalists, all dabbing their eyes; and beyond them virtually the whole of the rest of Britain, who have heard all this before, weren’t listening, and (had they listened) would have grunted, ‘But how’s he going to pay for this?’ and switched channels. The voters can now stand a dash more vinegar than politics or the media dare to give them.

Which brings me to Brighton, where I now write. I’m not sure that the media have noticed, but Jeremy Corbyn — for all that his policies are obviously crazy — is much more sparing with the schmaltz than ‘new’ Labour ever were. Blairism was all touchy-feely. Corbyn isn’t. Not only could he not do touchy-feely well, but he really doesn’t want to.

Proper Marxism (before Christian socialism wrecked its logical basis with a suffering-and-compassion agenda) is not about compassion, but about justice. Proper Marxism would see measures to mitigate the woes of the poorest as a capitalist distraction: an aspirin to dull the pain. Proper Marxism believes that only by restructuring the whole economic structure of our society can fairness be achieved — and all the rest is sops and sentimentality. Whatever they may protest, Mr Corbyn and his shadow chancellor, John McDonnell MP, are proper Marxists. They have a theory of politics: it’s intellectually coherent, straightforward, and taken on its own terms makes sense. But it’s all pretty dry stuff.

For all his steam-age dress and demeanour, I suspect that Jeremy Corbyn has ‘got’ the internet age better than we journos have. He knows how fast public sentiment can slosh this way — and then slosh that. David Cameron knows it too. These two, I’m afraid, have seen deeper into the dark heart of the British voters than the compassion-mongers in politics ever have.

We of the media have tended to laugh at the new young Britain that has flocked to join Labour as supporters or members, and that thrills to his message of injustice and his warnings about the Establishment. We speak of them as all heart and no head, an emotional flurry among a generation that in some ways has lost out in this century. They haven’t thought it through, we sneer.

No, maybe they haven’t. But what they will not be fobbed off with is soft-focus politics and speeches that go heavy on the sympathy for society’s victims, but light on the remedies. They like the dash of acid in Corbyn’s words. They like the impression that he has an analysis. They understand the meteorology of the social media — the storms, the laughter and the floods of tears — and crave a politics that cuts through it. If Corbyn can do this, then, though he will never win a general election, he will win a phalanx of support among voters that is solid, may endure, and may protect him from the attacks of Labour MPs. This he will do not by asking the public to weep with him, but by convincing a minority that he has a hard-edged plan. He does have a plan. He doesn’t waste tears. I like that about him.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in