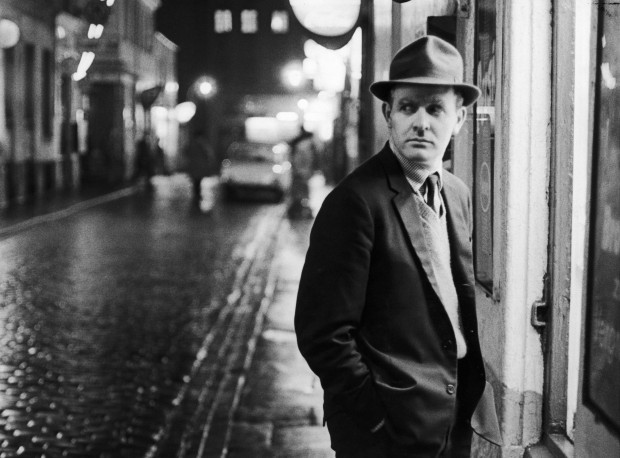

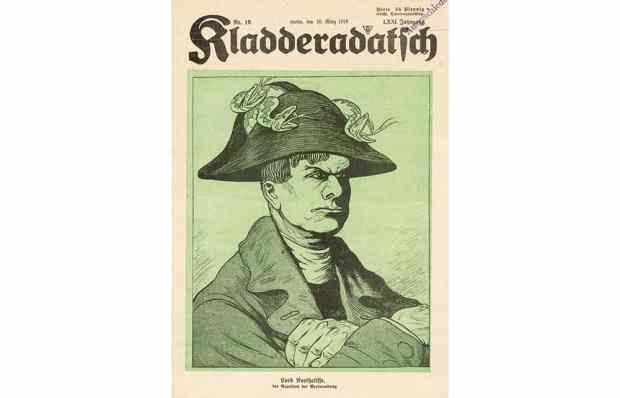

‘Have you got over your father yet?’ the 26-year-old David Cornwell was asked by MI5’s head of personnel when he joined the agency in the spring of 1958. And the answer, more than half a century later, has to be ‘no’. We knew of his conman father Ronnie’s cartoonish presence in Cornwell’s life, but never the extent to which he has dominated his very being.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £22 Tel: 08430 600033. Andrew Lycett is the biographer of Ian Fleming, Wilkie Collins and Arthur Conan Doyle.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in