On 13 March 2014 a congregation of 2,000 people, including many of the great and the good, gathered in Westminster Abbey for a memorial service for David Frost, who had died suddenly six months previously while travelling on the Queen Mary to America. During the service a select band, led by the Dean of Westminster, John Hall, retired to Poets’ Corner, sacred to the memory of Keats, Shelley and others of the immortals, where the Prince of Wales laid flowers on a tablet in the floor bearing the illustrious name of Frost. Given that in only a few years’ time Frost’s name, along with many of today’s celebrities, was likely to be forgotten, it might have been better to dedicate the tablet ‘To the Unknown Television Personality’.

Considering that he had never been a poet, and that, unlike many far more deserving than he, he had been fast-tracked, this extraordinary if posthumous feat of Frost’s marked a suitable climax to his career — one which had begun in 1939 in the humble home of a Methodist minister in Tenterden and led to success, fame and fortune on a lavish scale, to a knighthood, a beautiful country house, a titled wife, three fine sons all educated at Eton etc. Didn’t he do well? as his fellow TV knight Sir Brucie might well have observed.

Now comes the icing on the cake in the form of an ‘authorised biography’, rapidly completed in only a few months by an Irish writer and journalist Neil Hegarty. There are signs of haste about the book, so that while it describes at the outset the premature death while jogging of Frost’s eldest son Miles, he is on p. 413 still ‘building his venturecapital enterprise’. No doubt the publisher was more alert than the Church of England to the speed at which TV celebrities fade from view and was anxious not to delay things by altering the text.

It is called an authorised biography but it ought to be called an authorised hagiography. At the outset Hegarty tells us that Frost was ‘a man of great kindness, of sweetness of temper, of generosity and compassion… He projected a joie de vivre, a life force that was almost tangible.’ ‘Yes he was a legend,’ Lady Carina, his wife, adds in her Afterword; ‘A genius larger than life with a generosity of spirit that knew no bounds.’ To Wilfred, his son, he was simply ‘the greatest broadcaster who ever lived’. As for Lady Carina herself she has been, in the opinion of her sons ‘the most amazing wife, the most amazing mother’.

Poor Hegarty never had the good fortune personally to meet this saintly and legendary genius, to be greeted by him with his familiar cry ‘Super to see you!’ Instead, he says he has ‘absorbed his life osmotically’ by watching him on TV and talking to those who knew and admired him like the famous publisher Naim Attallah, who recalls lunching with Frost regularly in the Hyde Park hotel at the beginning of the grouse-shooting season in August:

He would eat his grouse with his hands, and it would get all over his face and his tie; and such a man is genuine — there is no hypocrisy. He loved women, and so do I.

Reading such encomia I feel no shame in admitting to having been one of those who mercilessly made fun of Frost throughout his career — and who can be dismissed by Hegarty as privileged snobs who envied the great genius for his success. But it wasn’t snobbery that lay behind the scorn; simply a healthy suspicion of an unconcealed lust for money and fame. That he lived in a different world from his fellow That Was the Week satirists was noted by Willie Rushton early on in their collaboration, when the TW3 team flew to Ireland for a TV appearance. As the plane prepared to land Willie saw Frost, who was obviously anticipating a press reception, consulting a little notebook entitled ‘Airport Quips’.

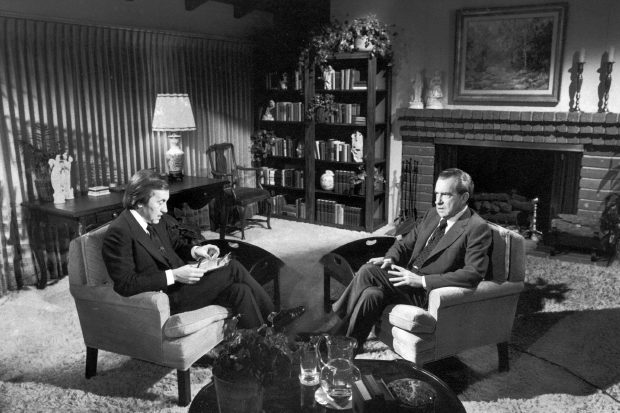

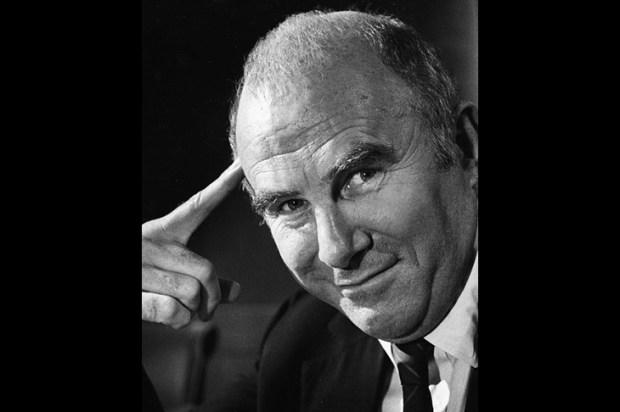

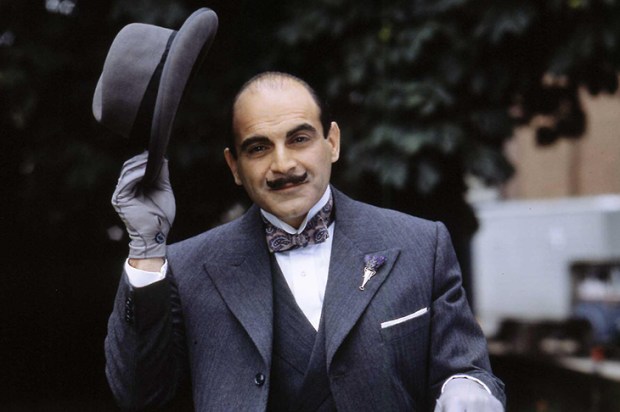

After those early satirical programmes pioneered by Ned Sherrin, Frost slowly emerged from his grubby chrysalis as a glamorous international celebrity who made a new and different name for himself as a TV interviewer, specialising in politics. In this role he has more recently been transformed into the protagonist of the Frost/Nixon play (and film), which apparently he watched so often that according to his friend Alastair Campbell he was able to mouth the lines from his seat in the stalls.

Unlike the Paxmans and Humphreys Frost was an effective interviewer because he was never combative, hence the famous admission of failure that he extracted from Nixon in 1974. ‘It was a big risk,’ Frost said afterwards; ‘people predicted that it wouldn’t be possible to get Nixon to say anything that wasn’t self-serving.’ He didn’t see that Nixon’s admission ‘I let down my country’ was as self-serving as everything else he said, and that it did Nixon a power of good as well as bringing him (and also Frost) a welcome stash of money. Both men benefited, thus confirming the opinion of Clive James (quoted here): ‘Frost and Nixon are remarkably similar… they understood each other well.’

A more considerable achievement came some years later on Al Jazeera, when he cleverly extracted a two-word admission of failure from Tony Blair, by referring to the Iraq invasion of 2003 in a subtly casual manner.

DF: But so far it’s been, you know, pretty much of a disaster.

TB: It has, but you see what I say to people….

Too late, Blair tried to talk his way out of the trap, but he was caught and had admitted for the first time that his intervention side by side with Bush had been disastrous.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £22 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in