By chance, my first night in Havana in 1987 was the night the clubs went dark to mark the death of Enrique Jorrin, the inventor of the cha-cha-cha, whose rhythmic brainstorm had gone global. My grandparents used to dance cha-cha-cha at Latin nights at the Grand Hotel in Leicester in the 1950s.

Rubén Gonzalez, Jorrin’s pianist, thought that his death spelled ‘the end of the old music’ and went into retirement, his piano destroyed by termites in the tropical humidity. Another contemporary who didn’t quite make his mark was Ibrahim Ferrer — he’d been in a moderately successful band Los Bucucos.

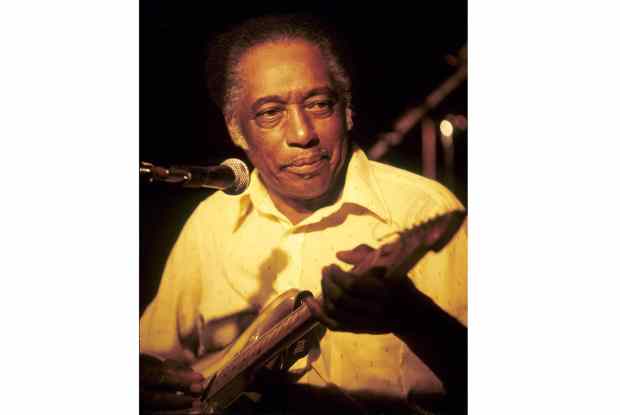

Ibrahim retired at about the same time, for similar reasons to Rubén — the work had dried up. Ibrahim, however, clung to what a santero (a local Afro-Cuban priest) had told him; that at the end of his life he would become celebrated. That seemed hopelessly far-fetched — he hit hard times and could be seen selling lottery tickets in the streets, and even shining shoes.

That they would go on to produce the bestselling Latin album in history seemed fantastical. But that’s exactly what happened when they became key members of the Buena Vista Social Club. Their eponymous first album would set off a boom not just in Cuban but in world music. Without any major promotion, that 1997 release rapidly sold a million. Wim Wenders’s film of the same name added rocket fuel to sales and it went on to sell eight million more. It became a number one in pop charts around the world. I toured with them to Japan, where they were selling out stadiums every night. Walking round Tokyo, they would stop the traffic.

Salman Rushdie called the summer of 1998 ‘that Buena Vista summer’ and before long hundreds of Cuban albums were released and thousands of Cuban musicians were touring the world and bringing much-needed hard currency back to Cuba. A tourism ministry official told me the album might just have ‘saved the Revolution’. Cuba became perhaps the only country ever where parents were disappointed if their offspring became lawyers rather than musicians.

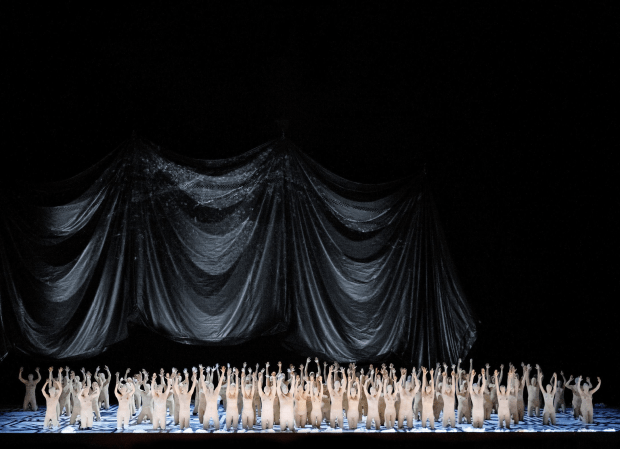

Various permutations of the group have been touring as the Orquesta Buena Vista Social Club ever since, with additional members joining as the older ones retired or died, but their last hurrah is the ‘Adios Tour’. Last Thursday saw a grand UK finale at a sold-out Royal Opera House.

The concert was tinged with sadness. There were short, beautifully assembled films of the deceased members including Rubén, whom I last saw in the Egrem studio in Havana after our Japanese tour. His short-term memory was completely shot, but he played ancient danzons from the 1920s to perfection. Ibrahim was, as their producer Nick Gold said, ‘the most spiritual’ of the group — self-effacing to the point of suggesting, when he was ill, that they get a replacement for the rest of his solo album.

There was a film of Compay Segundo, the oldest of the original group, who toured till he dropped at 96, attributing his longevity to daily cigars, a habit his grandmother had introduced him to when he was six. Bassist Cachaito Lopez was pretty astounding. It is a mystery how he plays the same, usually few, notes in the same, traditional Cuban style as other bassists, and often in the same order, but adds some magic to the extent that all the musicians in Havana recognise him as a master. The presence of the films made it clear that however technically adept their stand-ins were — the pianist Rolando Luna, for example — they hadn’t the genius of the originals. It seems a sensible move to pull the plug on the enterprise at this point.

There were, thankfully, a few artists from the original album at the Opera House, such as Barbarito Torres, the laud player (like a lute), and, far stage right and not quite his old self, the great trumpeter Guajiro Mirabel. Of the singers on the album Omara Portuondo, now 84, camped it up and just about got her voice round ‘Dos Gardenias’, that great bolero she sang with Ibrahim. I always slightly meanly thought she was a good cabaret singer who got lucky. The other original singer, still in fine fettle, was the cowboy-hatted Eliades Ochoa, who has hardly ever played with the Orquesta but sang ‘El Carretero’ and the lead on the best-known Buena Vista song ‘Chan Chan’, which got a restrained Opera House audience on its feet.

As producer Ry Cooder said of the album, ‘We certainly didn’t expect to be driving around in fancy cars’ as a result of its success. More poetically, of an album of wonderfully performed songs, and a record of a great musical culture that had been cut off for decades, he said, wistfully, ‘We caught the tail end of a comet.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in