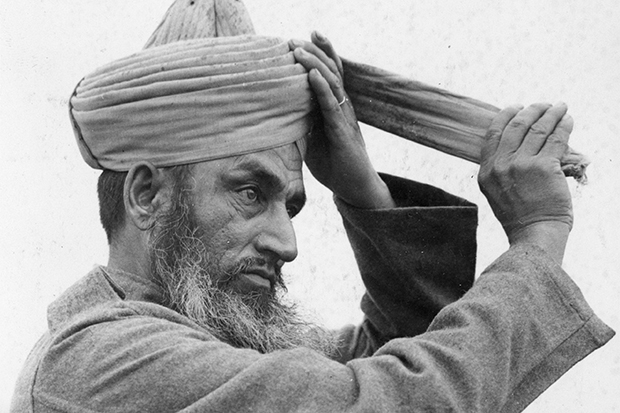

‘Lobbying,’ writes William Waldegrave in this extraordinary memoir, ‘takes many forms.’ But he has surely reported a variant hitherto unrecorded in the annals of politics. The Cardinal Archbishop of Cardiff (‘splendidly robed and well supported by priests and other attendants’) had come to lobby him (then an education minister) against the closure of a Catholic teacher-training college.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in