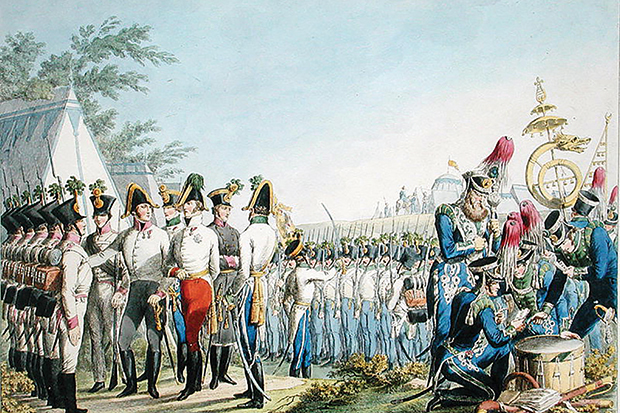

John Keegan, perhaps the greatest British military historian of recent years, felt that the most important book (because of its vast scope) that remained unwritten was a history of the Austrian army. Richard Bassett has now successfully filled the gap, and few could be better qualified to do so. During many years as the Times’s correspondent in Vienna, Rome and Warsaw, he made friends with most of the leading local experts, as his acknowledgements testify.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20 Tel: 08430 600033. John Jolliffe is the translator of Froissart’s Chronicles and the editor of Raymond Asquith: Life and Letters.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in