This week I continue with my analysis of Nigel Short’s recent animadversions upon the differences between the male and female brain and his opinion that women cannot match up to men across the chessboard. The great German poet Goethe once described chess as ‘a touchstone of the brain’; he wrote this, in fact, in the persona of a female character, Adelheid, in his play Götz von Berlichingen.

The brainiest person I know is a female triple PhD from Dubai, Dr Manahel Thabet, who is capable of expressing herself in equations way beyond my comprehension. The predominance of male chess players is, in my opinion, not the result of differing brainpower, biologically divergent ‘hardwiring’, as Nigel put it, but of certain predominant cultural conditions. These include the long-held belief in the west that it was improper for women to become chess professionals.

Equally restrictive was an article of faith amongst former Eastern bloc nations, the greatest state supporters of chess the world has ever seen, that male and female chess players should be segregated into separate tournaments. If you start with a smaller and less experienced pool of players and force everyone in that pool to stay there, this will necessarily impede progress. Even in Soviet Georgia, the most fervent advocate of female chess, this ghetto mentality still predominated in official chess circles, as it did in communist Hungary, home of the brilliant Polgar sisters, who broke out by rebelling against the system and insisting on facing male opponents.

The segregation was based on a false analogy with physical sports, where upper body and general muscle strength counts. In chess, bodily stamina is important and so is brainpower, but muscular strength is not.

So Nigel Short’s views may reflect the current situation, but the explanation he gives is possibly not the correct one.

Judit Polgar’s lifetime score against Kasparov is unimpressive. Just one win for her, as opposed to many losses. But even a sole victory against Kasparov is an impressive feat.

Kasparov was felled by the chessboard amazon after unwisely selecting the Berlin Defence, which leaves Black on the defensive and is inimical to his quintessentially energetic style.

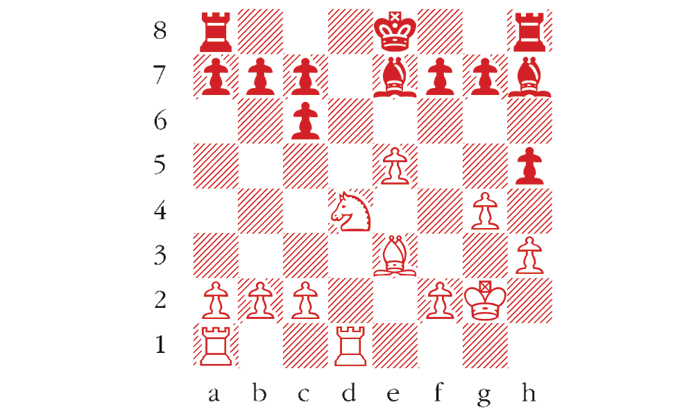

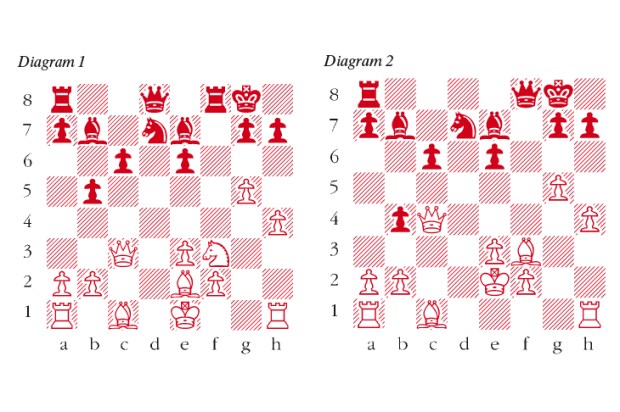

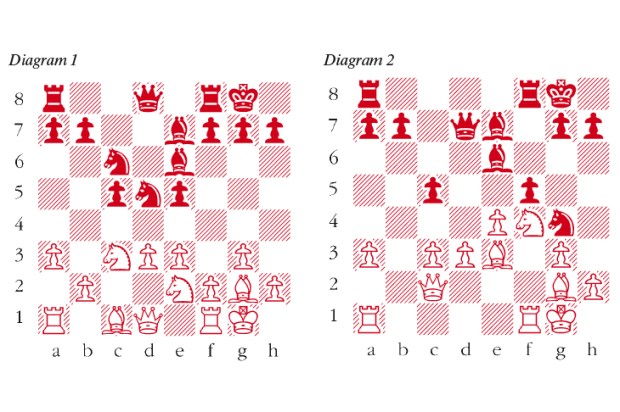

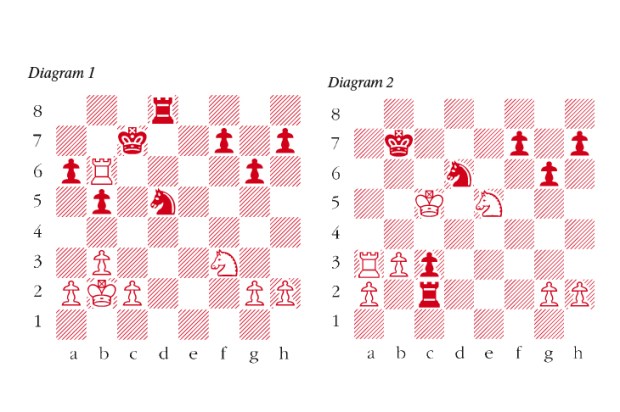

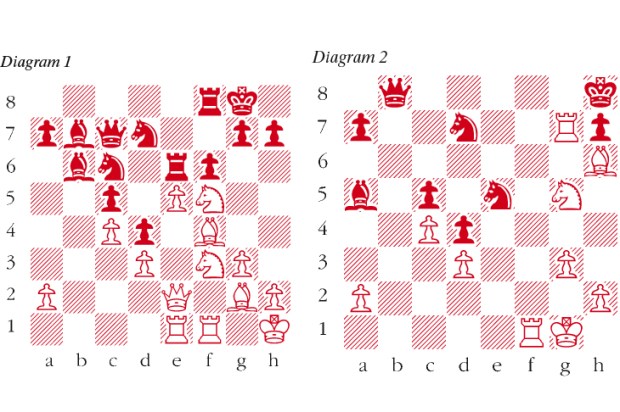

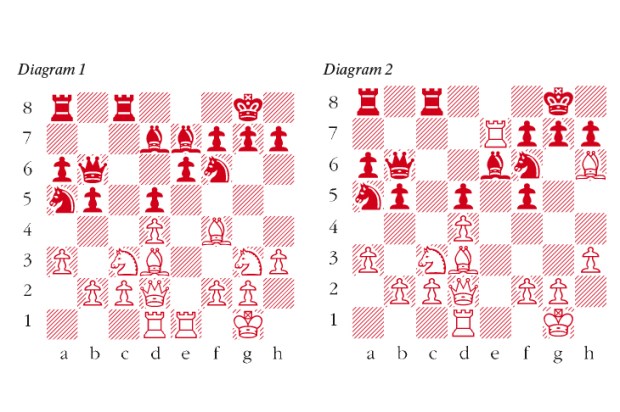

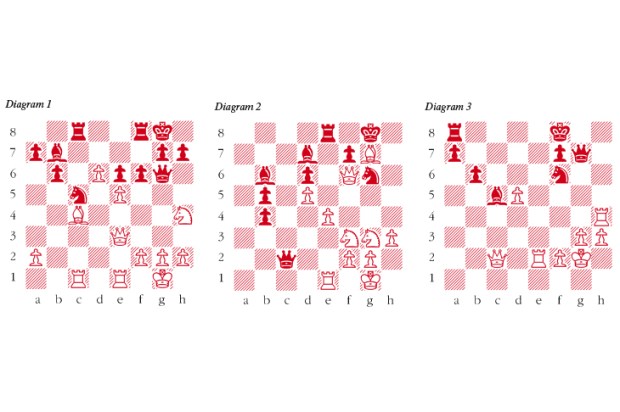

Polgar-Kasparov; Russia-the World, Moscow 2002 (see diagram)

Kasparov has misplayed this Berlin Defence and White has all the play. 18 Nf5 Bf8 19 Kf3 Bg6 20 Rd2 hxg4+ 21 hxg4 Rh3+ 22 Kg2 Rh7 23 Kg3 f6 Black’s problem is that the natural 23 … Rd8 runs into 24 Rxd8+ Kxd8 25 Rd1+ Ke8 26 Bxa7. The bishop cannot be trapped since 26 … b6 is met by 27 Bb8 and the bishop escapes. 24 Bf4 Bxf5 25 gxf5 fxe5 26 Re1 Bd6 27 Bxe5 Kd7 28 c4 c5 29 Bxd6 cxd6 30 Re6 Rah8 31 Rexd6+ Kc8 32 R2d5 White’s extra pawn is doubled but her active rooks are her main asset. 32 … Rh3+ 33 Kg2 Rh2+ 34 Kf3 R2h3+ 35 Ke4 b6 36 Rc6+ Kb8 37 Rd7 Rh2 38 Ke3 Rf8 39 Rcc7 Rxf5 40 Rb7+ Kc8 41 Rdc7+ Kd8 42 Rxg7 Kc8 Black resigns After 43 Rxa7 Kb8 44 Rae7 White wins easily.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in