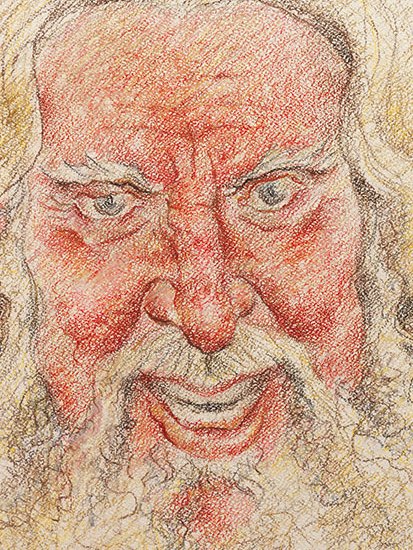

Understandably given its bulk, Antony Sher’s Falstaff in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s recent production of Shakespeare’s two Henry IV plays had a long period of gestation before it emerged, fully formed and laughing, from under the covers of a bed also occupied by Prince Hal and a couple of prostitutes.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £15.29 Tel: 08430 600033. Stanley Wells is a Shakespearean scholar. His Great Shakespeare Actors is published this month.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in