Lesley Blanch (1904–2007) will be remembered chiefly for her gloriously extravagant The Wilder Shores of Love, the story of four upper-class European ladies who abandoned their natural habitat to seek and find romance in the Middle East. If one had to pick only one of Blanch’s books to read there could be no better choice than this; but, as this exotic potpourri reminds one, she was incapable of writing boringly or badly.

The most substantial part of Lesley Blanch: On the Wilder Shores of Love (a title which seems designed to deceive putative readers into thinking that they have read it all before) is Blanch’s record of her youth — the opening chapters of a book which she did not live to complete. Then follows a selection from the many articles she wrote over the years for Vogue, a memoir of her marriage, and chapters on her extensive and usually eccentric travels around the world.

Her marriage to Romain Gary, which brought her much joy as well as misery, provides the most memorable passages of this book. Gary is now largely forgotten (in Britain at any rate), but when he won the Prix Goncourt for The Roots of Heaven he was one of the most celebrated authors in the world. If Blanch is to be believed (not always possible, for she habitually adopts a splendid indifference to the facts), Gary was witty, intelligent, sensitive and almost irresistibly attractive to women. He was also selfish, untrustworthy and an inveterate womaniser. When asked who he would like to be if he were not Romain Gary he replied ‘Romain Gary’ — a riposte which Blanch considers to be ‘typical of his dark humour’, but which also demonstrates the arrogance and vanity which marred his personality.

Blanch, when she put her mind to it, could be remarkably difficult as well, but she was far nicer than her husband. Her prose style was like her personality, lushly romantic but corrected by an astringent common sense. She travelled endlessly, often in parts of the world where solitary European ladies were almost unknown. Afghanistan she ‘loved passionately’. One of its charms was that it had no railways:

It was by road that I first came to know something of its savage yet lyrical beauty, scarcely changed since Genghis Khan’s horsemen rode there and the Emperor Babur lingered in its gardens. Ah, Afghanistan!

‘Ah, Afghanistan!’ indeed; but equally ‘Ah, Paris!’ and ‘Ah, Mexico!’ Wherever she went she trailed clouds of glory, finding romance and excitement even in the most unpromising environment. Life for and with Lesley Blanch was sometimes frustrating, often uncomfortable but never dull.

She drops names with reckless abandon. She mentions casually: ‘Many years later, when Garbo came to see me… she was wrapped in a nondescript overcoat and wore pink bed-socks inside her espadrilles.’ Two pages later André Malraux invites her to spend a weekend with him in Washington. A little further on: ‘I was sitting on a sofa between Edith Sitwell, magnificent in her priestess robes, and Marlene Dietrich in a glittering black sheath. Stretched across our knees was Truman Capote.’ No doubt they all did feature in her life — Blanch was the most beguiling company — but even if they had not she would have had no compunction aboutpretending they did. She loved her life and wanted to make it equally enjoyable for her readers; dry reliance on the facts was not at all her style.

Will Lesley Blanch still be read in 100 years? She has a better chance than many of her more portentous contemporaries. Once met she was not easily forgotten. Anne Scott-James wrote:

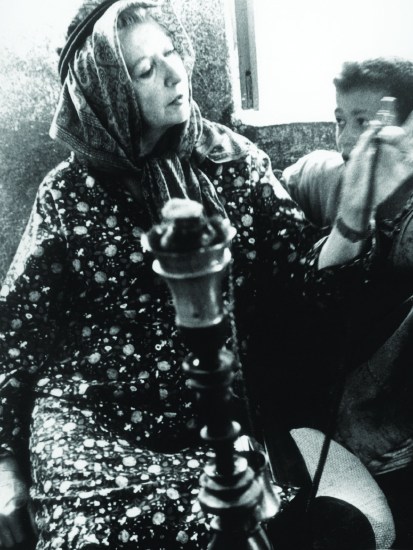

Everything about her was abundant: her talents; her talk; her friendships; her travels, her experiences. Even her appearance was rococo. With her rounded figure, wide, innocent eyes and gold, curling hair, she reminded you irresistibly of a gilded cupid, knowing neither vice nor virtue, but playful and loving, pouring out affection, humour, ideas, plans, stories, words from her rich cornucopia of personality.

On the Wilder Shores of Love brings that personality vividly to life. It is well calculated to impel readers back to The Wilder Shores themselves and thence to her other masterpieces, The Sabres of Paradise or her incomparably eccentric exercise in autobiography, Journey Into the Mind’s Eye. Much pleasure awaits them if they follow this course.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £17 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in