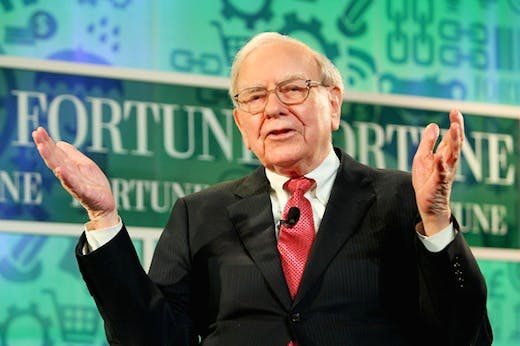

God it’s nauseating when an exact university contemporary of yours turns out to have become a hugely successful investor with a fund worth many millions. The bit during our meeting where I most wanted to throw up my ravioli was when this fellow — Guy Spier his name is; read PPE at Brasenose with my old mucker Dave Cameron at the same time I was at Christ Church — told me how he’d once paid nearly £250,000 in a charity auction just for the privilege of having lunch with Warren Buffett.

A quarter of a million quid. Imagine all the things you could do with that. I could make a thousand and one such wish lists, I reckon, and no matter how many I compiled I still very much doubt a single one of them would include: ‘Blow the lot on lunch with the Sage of Omaha.’

But the rich, as we know, are different. One way that they’re different is that they’re much better than the rest of us at making money. This is something I found most definitely to be the case with Guy Spier. By the end of my lunch, I felt much the same way about Spier as I know he did after his lunch with Buffett: that the knowledge he had imparted was so valuable that even if I’d paid (which I didn’t: he being so much richer than me it seemed obscene not to let him foot the tab), it would have been worth many hundreds of times the outlay.

In Spier’s case this knowledge was extremely hard won. After Oxford and Harvard Business School, he was far too impatient and arrogant to waste any time learning the trade and paying his dues. Instead, he headed straight towards where he imagined the real money was: to a New York brokerage firm nearly as toxic as the one in The Wolf Of Wall Street.

Eighteen months later, he left riddled with self-disgust, having made no money and with his reputation in tatters. Such was the company’s low repute that simply no one in the financial industry would employ him. A less determined man might have found a different career, but not Spier. The secret to making money, he had intuitively grasped, is first to turn yourself into the kind of person who is good at making money. And who better to model himself on, in this respect, than the most successful investor of the last 100 years, Warren Buffett?

So that is what he did. In financial terms, this meant renouncing the excitement of shorting, of bubbles (like the tech one in the 1990s), of vertiginous rises and headlong falls, in favour of the slow, plodding business of value investing — that is, spotting which companies are going to do well and then backing them for the long run, confident in the knowledge that your clients’ portfolio will increase steadily over time.

Warren Buffet Photo: Getty

Warren Buffet Photo: Getty

Amazingly — and in my view this more than reason enough why PPE should be banned and replaced by something more useful like needlework or My Little Pony studies — he had been taught at Oxford something called the efficient markets hypothesis. This theory holds that ‘financial prices reflect all of the information available to participants in the market’. It’s self-evidently bollocks, yet Spier, one of the brightest undergraduates in his year, had swallowed it without question. Maybe that’s why there aren’t more value investors in the City: maybe these people actually believe that there’s no point trying to seek hidden value in the market because it will already and always be ‘in the price’.

Anyway, once Spier had got that theoretical nonsense out of his system, he was in a much better position to make money the Warren Buffett way. This means, first of all, being able to study a company’s balance sheet, decipher what the auditors are really trying to tell you (or not tell you), as opposed to what the management would like to tell you, and decide whether it’s the Apple of the future or a pile of pants.

But I don’t want to dwell on the financial aspects of his career: you can get all that from a book he’s just written called The Education of a Value Investor. What interested me more about his story were the more esoteric techniques he used to propel himself from near-abject failure to his current Master of the Universe status. A lot of this has to do with realising that the quest for value extends far beyond financial markets into a whole way of thinking about how to live your life.

One of these is learning to shut out the noise and to concentrate on what really matters. That’s why he decided to quit the buzz of New York in favour of the pleasant boringness of Zurich, where the public transport system is so good that even billionaires use it. He located his office well away from the financial centre (so he wouldn’t be distracted by the violent mood swings to which brokers are prey as markets, especially in these uber-volatile times, rise and fall) — and also, following the model of Buffett (who operates out of dull-as-ditchwater Omaha), ensuring that he had just a ten-minute commute from home (long enough to establish a psychological separation; short enough never to be a chore).

Some of the tricks he describes may be rich man’s luxuries. Most are not. At the bottom of his philosophy is this: the happier you are in your skin and the better you are at making others happy in their skin (e.g. writing lots of nice friendly notes), the more easily you’ll generate an environment in which you thrive not just personally but financially.

I went to meet him mainly because I’m fascinated by rich people and how they got rich. It was a good call. This Guy has changed my life. Watch this space.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in