It’s surprising how many perfectly good bridge players lack confidence when it comes to squeeze plays. They seem to think a squeeze is some sort of dark art which experts alone can master — a view no doubt reinforced by all that technical jargon about ‘rectifying the count’ and ‘isolating the menace’. But the truth is that many squeezes are within any reasonable player’s grasp — in fact, even beginners have a chance of executing one simply by playing off all their winners and hoping for the best.

My favourite example of a near-beginner pulling off an intricate squeeze by fluke was shown to me some years ago — I forget declarer’s name, but I’d like to take this opportunity to wish all Spectator readers at least one hand like this in the new year:

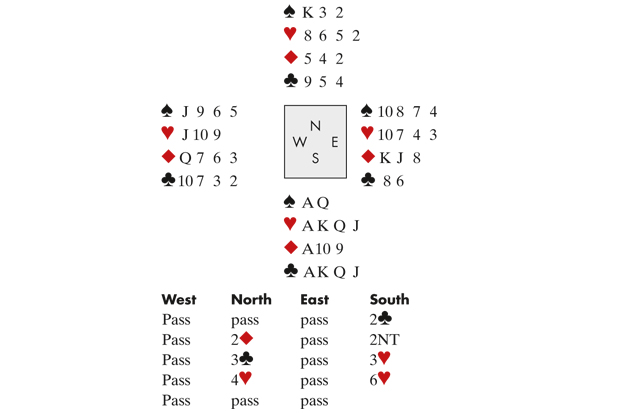

West led the ♦3 to East’s ♦K and South’s ♦A. South drew trumps. When they split 4–1, she could count only 11 tricks: the ♠K was stranded in dummy. She cashed her winners, coming down to ♠Q ♦109 opposite ♠K3 ♦5. Next she played the ♠Q and exited with the ♦10. West won with the ♦Q, East’s ♦J fell under it, and West’s last card was a diamond which went to South’s ♦9 — slam made!

As it happens, E/W were experts so they could explain how they’d been squeezed. In the three-card ending above, one defender had to keep two diamonds or she could simply concede a diamond: the other had to keep two spades or she could overtake the ♠Q with the ♠A and cash the ♠2. So when she cashed the ♠Q and exited with a diamond, if the opponent with honour-doubleton won, their honour would swallow up their partner’s (as had happened); and if the opponent with just one diamond won, they would have to play their last card — a spade — to dummy’s ♠K. And that, by the way, is what’s known as a ‘stepping-stone’ squeeze.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.