There’s an irony about Ukip’s rise. Nigel Farage party’s popularity is driven by a widespread sense that the main parties are all the same. Yet in the past four years, the differences between the Labour party and the Conservatives have grown substantially, on issues from the size of the state to an EU referendum.

In an election year you might expect parties to converge in the centre ground as they chased swing voters. It won’t happen this time. Labour is determined to stop left-wingers defecting to the SNP and the Greens, while the Tories, who have long had their own issue on the right because of Ukip, believe that their best chance of victory comes from heightening the contrast between them and the other parties.

Labour, the Tories and the Lib Dems do still agree on some things. On immigration, none challenges the fundamental principle of free movement within the EU — something for which Ukip should give thanks. On energy, the three main parties are all behind the Climate Change Act, with its absurdly ambitious targets for reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, which will push up both domestic and industrial energy bills. Tellingly, Douglas Carswell chose energy policy as the topic of Ukip’s first parliamentary debate. Then there is international development. All three Westminster parties commit to spending 0.7 per cent of Britain’s gross national income on overseas aid, against the wishes of two-thirds of the public. Here, too, Ukip can present itself as the party prepared to shake things up.

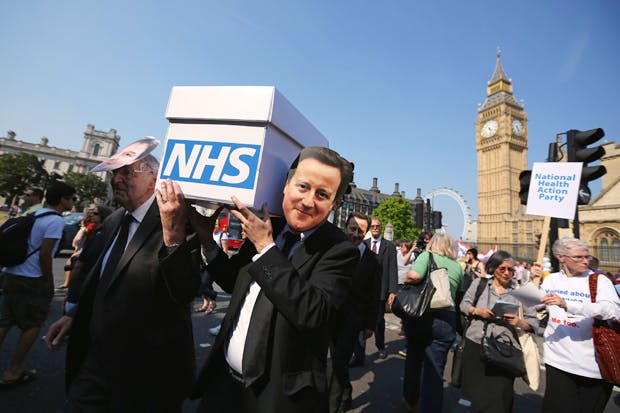

But when it comes to the NHS, Ukip is racing to join the consensus. Until recently, it was the only party that would tolerate public discussion of different ways to fund health care. Two-and-a-half years ago, Nigel Farage talked about moving towards an insurance-based system. But now Ukip is trying to be more Catholic than the Pope on the subject, opposing the EU-US free trade deal on the grounds that it might force NHS privatisation and even standing against the efficiency savings that the coalition has made.

When Carswell was a free-thinking Conservative backbencher, he proposed — with his friend and ideological compadre Dan Hannan — that government should ‘allow patients to opt out of the NHS and instead pay their contributions into individual health accounts’. Since joining Ukip, he hasn’t publicly repeated this sentiment. Instead, he and Ukip’s other MP, Mark Reckless, have voted for a Labour Private Member’s Bill that would unwind some of the very limited competition measures that the coalition has brought in.

Ukip has shifted because, ironically, it has come to the same conclusion as the Tory modernisers: acceptance of the current NHS settlement is the price of admission to British politics. For all its boasts of saying what the other parties don’t dare to, when it comes to the NHS, Ukip’s courage fails.

And Farage and his team can’t be blamed for being afraid. As Nigel Lawson, a former editor of this magazine, wrote in his memoirs, ‘The National Health Service is the closest thing the English have to a religion.’

Logic goes out of the window when it comes to health debates. The Tories boast about how they have pumped money into the NHS, implicitly accepting the left’s argument that how much you spend on a service is the best gauge of its quality. Labour boasts of a ‘zero-based spending review’, rigorously assessing from scratch the best use of every pound that taxpayers hand to the government. But it is committed to putting £2.5 billion more into the NHS than the coalition, whatever its review finds.

To listen to Andy Burnham, you would think that there was a major division between the Conservatives and Labour on the NHS; that David Cameron was selling it off. But if the NHS is being privatised under this government, then it was being privatised when Burnham was health secretary. Labour politicians seem to believe that it’s fine for them to let private contractors into the health system, but not for anyone else to.

If the state of debate about the health service is depressing, one reason for hope is Simon Stevens, the new chief executive of NHS England. Stevens was the architect of many of the Blair-era health reforms and, while he wants more money for the health service, his presence should ensure that the extra cash is accompanied by at least some reform.

Indeed, if the Conservatives are sensible — and if they are still heading the government after the next election — they will let Stevens continue with his quiet programme of reform. One of the big problems with Andrew Lansley’s Health and Social Care Act was that it gave defenders of the status quo something to rally against. Stevens’s more piecemeal approach makes that harder.

There is some frank debate about the NHS in Parliament. But it is happening in the relatively non-partisan confines of the Commons Health Select Committee. The committee’s chair, Sarah Wollaston, has been prepared to talk candidly about some of the funding options that the NHS might have to explore in time.

But if neither the scandal at Stafford Hospital, where patients were reduced to drinking dirty water out of vases, nor this era of fiscal retrenchment can prompt a proper, serious conversation about the health service and its future then it is difficult to see what will. There is simply no great appetite for the reformation of our national religion. As long as that is the case, even the self-styled iconoclasts of our politics will continue to worship at the NHS altar.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in