The author of this primer to the long-overdue Chilcot report, a retired sapper (Royal Engineers) major-general, nails his colours to the mast in the opening paragraph.

The British High Command made a number of judgments with poor outcomes in the decade from 2000 to 2010 when fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan… The outcome in some eyes has been humiliation, accusation of defeat in Basra, an unexpected high level of conflict in Helmand and significant loss of life for our servicemen and women as well as local civilians — so far, without the compensation of it all being worthwhile.

As a result:

The UK’s military leadership has lost much of the inherent trust and goodwill that it once enjoyed and people, with some justification, question its competence. Whilst widespread affection remains for the military body, faith in its top officers has been severely wounded following the events of Iraq and Afghanistan.

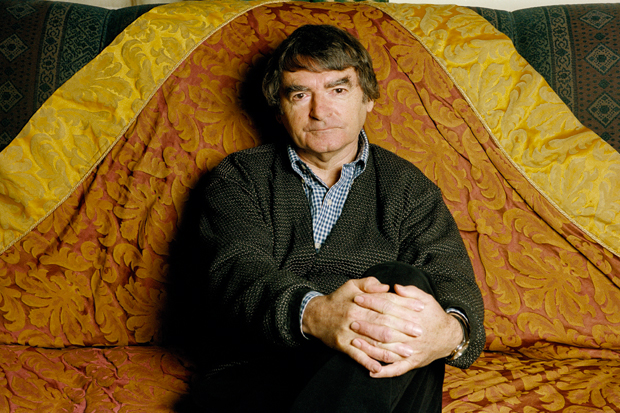

High Command sets out to be an agenda for reform as well as a narrative. The first part is about how the MoD ‘works’. Christopher Elliott, who was a cerebral officer possessed also of military nous, begins by recounting his own experience of being posted to ‘Main Building’ as director of military operations, despite never having worked there before. He does so in terms that Evelyn Waugh could not have bettered. His first morning in perhaps the most important one-star job in the MoD is pure Sword of Honour.

He is at some pains to explain and expose the limitations of the services’ own brand of political correctness — ‘jointery’. Or rather, where the principle of inter-service cooperation is taken to excess, to mean interchangeability of officers in khaki and light or dark blue. Whereas senior army officers are generalist and collaborative by upbringing, Elliott suggests, their naval counterparts are far less so, ‘isolated’ by the nature of command at sea and early specialisation, while RAF officers have ‘linear’ minds.

Though Elliott believes the MoD’s ‘public servants [were] acting with integrity and high moral purpose… the system was perfectly capable of generating complexity out of simplicity’. The underlying problem with Iraq and Afghanistan, he argues, was the ambiguity of purpose, which in turn led to confusion and even counter-productivity at the various levels of command. After 9/11, British policy — Tony Blair’s policy — was simply to stand side by side with the United States in ‘whatever’. (Incidentally, the author’s unfortunate habit of referring to ‘Prime Minister Tony Blair’, as if the office were a title, gives unintended force to the accusations of presidential delusion.) But Blair could never with true candour present his policy thus, and therefore the architects of military strategy — if they understood the game at all — could not truly articulate the ways to achieve the ends of policy; and could not, or were not willing to, provide the means to enable the ways. On the ground the troops were doing their best to fight what they thought was a necessary battle, and frequently calling for more resources, while being told in as many words by the Permanent Joint Headquarters in the London suburb of Northwood that the battles were not really necessary; or, indeed, by the Chief of the General Staff, Richard Dannatt, that they themselves were ‘part of the problem’.

The terrible irony is that Blair’s admirable policy objective of being alongside the Americans — for that is surely our long-term safeguard — may have been undermined by the tactical failure in Basra and the mess that was Helmand.

But a fish rots from the head, and if that was true in the case of national strategy and No. 10, it was certainly the case with military strategy and the MoD. And while Elliott tends to pull — or perhaps mask — his punches, it doesn’t take a trained referee to see where the blows are meant to fall. Besides vacillating and frequently changing secretaries of state, and indifferent senior civil servants, the three successive Chiefs of Defence Staff (CDSs) — one general (Walker), one admiral (Boyce), one air marshal (Stirrup), all now raised to ceremonial five-star rank, and ermine-trimmed — are to varying degrees ‘the guilty men’.

What emerges in Elliott’s study is the astonishing lack of collegiality at the top of the MoD, the lack of record of decision-making, and the sheer evasion — or, at best, lack of clear lines of authority and accountability. One CDS — Stirrup — says that as he did not, constitutionally, command anyone, ‘they could have disobeyed me’. Yet the single-service chiefs — several of them claim — were not brought into discussions of strategy. Oh yes they were, say the three CDSs, but Elliott concludes that they weren’t — or certainly not adequately. The answer, of course, ought to be in the minutes of the chiefs-of-staff committee meetings, but, tellingly, when Dannatt becomes CGS, baffled as to how, why and when the decision was taken to go into Afghanistan, he reads all the minutes and can find no record of it.

General David (Lord) Richards, the last CDS, who having commanded the Nato corps in Afghanistan bore the scars of the confusion, vowed before taking up the post to restore chiefs-of-staff collegiality, which he appears to have been able to do despite the efforts of the Levene report and the civil service to rusticate the service chiefs.

There are errors in the book, some of them of proofreading, some of research. It was, for example, Richard Dearlove, head of SIS, not John Scarlett, chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee, who reported that in Washington ‘the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy’. And there is some unwonted criticism, such as that of General Sir Michael Rose in Bosnia, for the UN Security Council had already passed Resolutions 824 and 836 establishing six ‘safe’ areas by the time he arrived in 1994. Nevertheless, High Command provides probably the best basis for reform that the MoD is likely to see for some time.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in