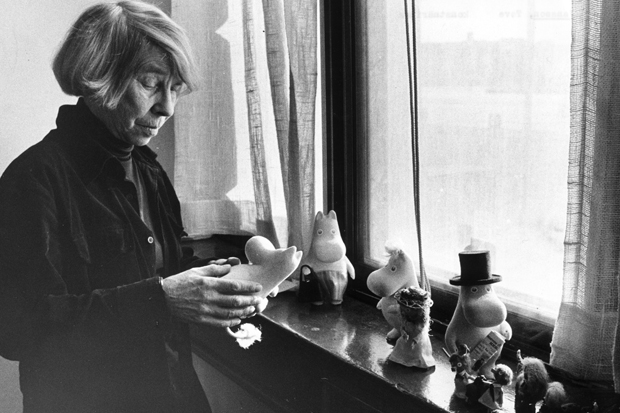

Tove Jansson’s father was a sculptor specialising in war memorials to the heroes of the White Guard of the Finnish civil war. He did not like women. They were too noisy, wore large hats at the cinema and would not obey orders in wartime. Tove used to hide to spy on his all-male parties, where everybody got astoundingly drunk and attacked chairs with bayonets.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.50 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in