Voters explain their apathy about politics on the grounds that the politicians do not understand them. No surprise there, an ancient Greek would say, since the electorate does not actually do politics. It simply elects politicians who do, thereby cutting out the voters almost entirely.

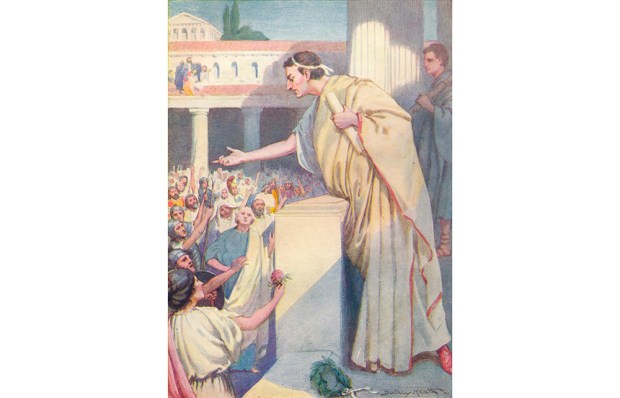

But the contrast with 5th and 4th century bc Athens does not simply consist in the fact that all decisions, both political and legal, were made by the Athenian citizen body meeting every week in Assembly. As Pericles’ Funeral Speech (430 bc) famously demonstrates, what is so striking about Athens is that the nature of the world’s first (and last) genuine democracy and the importance of preserving it were the subject of constant public debate.

Take the prosecution that the 4th century bc Athenian statesman Demosthenes brought against one Meidias, for assaulting him during a play-festival in the theatre of Dionysus. Though no serious harm was done, Demosthenes explained why he had brought the case — because Meidias’ assault was a threat to the very essence of Athenian democracy and its commitment not only to justice but also to the freedom, equality and security of every citizen. To summarise: Meidias was filthy rich. So he thought he could get away with it, as if the law counted for nothing. But the law was all that stood between the arrogant rich and the threat they posed to every ordinary citizen. That bulwark would survive only if every citizen was an active participant in the democracy: for ‘the laws are powerful through you, and you through the laws’.

Nothing there about ‘inalienable rights’, only active citizenship. So who is making the case for our system? If no one, why not? Is it because, like the EU, it needs reform? And if so, how? (Forget the Lords: only Parliament counts.) Consider, for example, the Scots’ referendum. People were actually doing politics then, because they made the decision. Hence the huge turnout. Is there a hint there? After all, every politician applauded. Or was it just crocodile applause? Is it the politicians at fault, not the system?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in