Like many of my generation I was enchanted by the surrealistic irreverence of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, until I overheard other boys — it was never girls — excitedly murdering the Parrot Sketch: ‘Ah yes, the Norwegian Blue — lovely plumage…’ This was not out of a snobbish disdain for popularity; I still loved the Beatles, after all. What made me wince was that the boys in question obviously lacked any sense of humour, and had adopted the show as a kind of prosthesis — which would explain its huge success in Germany.

This planted in me the appalling suspicion that Monty Python wasn’t really funny at all, and earlier this year, as the humourless boys held mass rallies at the O2 Arena, that suspicion was confirmed when I watched some old clips on YouTube. Beneath their undergraduate wackiness, the jokes are as desperately conventional as Dick Emery’s.

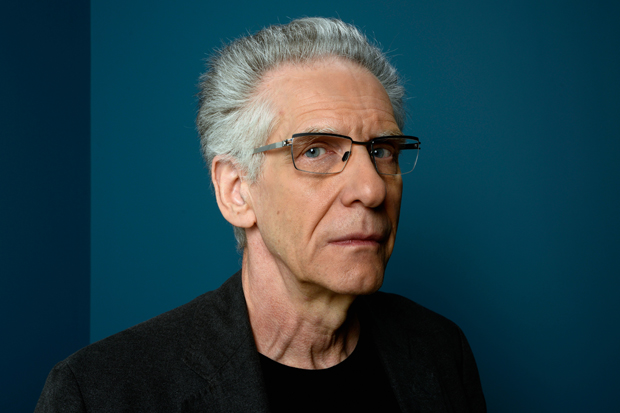

No one loves a critic, especially not performers, but John Cleese’s hatred of the trade is remarkable even for a performer, so it is sporting of him to include in his memoirs the New York Times’s response to Cambridge Circus, the revue that made his name, taking him from the Footlights to Edinburgh and the West End, and then on to New Zealand and America: ‘The visitors behave as if what they are doing, singing or saying is hilarious, but what emerges seems obvious or pointless.’ Fawlty Towers is clearly a masterpiece, and Cleese’s performance in Michael Frayn’s Clockwise is superb; farce, performed with utmost seriousness, is his great love. But the Times’s verdict seems to me applicable to nearly all his sketches.

Cleese turns out to be a stern critic himself, pronouncing that the ‘rather simplified psychology’ of P.G. Wodehouse’s characters ‘forces me to regard him as a very good comic writer rather than a great one’. He is more indulgent of his own work. He bulks out So, Anyway… with many sketches he wrote for the Python forerunners At Last the 1948 Show and How to Irritate People, as they are ‘really funny (in my opinion and it’s my fucking book)’. The first of them, featuring a psychiatrist and his patient, gives a fair idea of their groan-worthiness:

Tim Brooke-Taylor: ‘I think I’m a rabbit!’

John Cleese: ‘You stupid loony! ’Course you’re not a rabbit! Pull yourself together!’

Writing good comedy, he explains, is ‘exceedingly difficult’, and ‘being really funny is much harder than being clever or witty’. It is harder still to be all three, which is what Beyond the Fringe achieved.

Though he mentions Python quite often, Cleese’s narrative effectively ends with the recording of the show’s first sketch, ‘Flying Sheep’, in August 1969, though a final chapter covers the O2 rallies, which he compares to those held by Hitler at Nuremberg. On the second night, he recalls, ‘I found myself thinking: “How is it possible that I’m not feeling the slightest bit excited?”’

So the Life of Cleese deals with his previous 30 years, beginning with his birth near Weston-super-Mare. As ‘the only child of older, over-protective parents’, he was ‘a weedy, namby-pamby little pansy’. He adored his father, an insurance salesman who had changed his name from ‘Cheese’ to ‘Cleese’, apparently so he could fight in the Great War; his son was naturally called ‘Cheese’ at school, and has ‘always preferred’ it to ‘Cleese’, ‘which is, quite simply, not a proper name’. He loathed his mother, who used to beat up his father. He blames her for his difficulties with women, and for his many years in therapy, but her irascibility has surely been useful in his comedy: ‘Her rage filled her skin until there was no room left for the rest of her personality.’

The Cleeses moved house a lot, which he thinks nurtured his creativity. They always ate chicken at Christmas, and never went on holiday abroad, spending ten days every August at a Bournemouth hotel called Devon Towers. At his prep school (St Peter’s in Weston) ‘Cheese’ grew inordinately tall — 5’3” by the age of nine, and over six foot before he was 12.

He continued to grow as a day boy at Clifton, where he excelled at science and belatedly discovered that life isn’t fair. In his last year, ‘wounded’ that he hadn’t been made a house prefect, he ‘responded rather splendidly’ by throwing away his house cap, and wearing that of a rival house. After two happy years teaching at St Peter’s, he went up to Downing College to read law, and found his spiritual home at the Footlights.

Gosh it’s dull, this book — a dreary combination of pompous self-congratulation and tetchy sarcasm! There’s some rather predictable malice (Bill Oddie ‘could be prickly’ and ‘a bit obtuse’), and the odd diverting flash of weirdness — ‘I have always had an extensive collection of soft toys (I buy them pretending they are for children)’ — but the only time I laughed was at a grammatical error (‘Like Graham and I, Michael and Terry, and Eric were primarily writers’). As Cleese justly observes, ‘It’s a nightmare once comedy stops feeling funny.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in