Listen

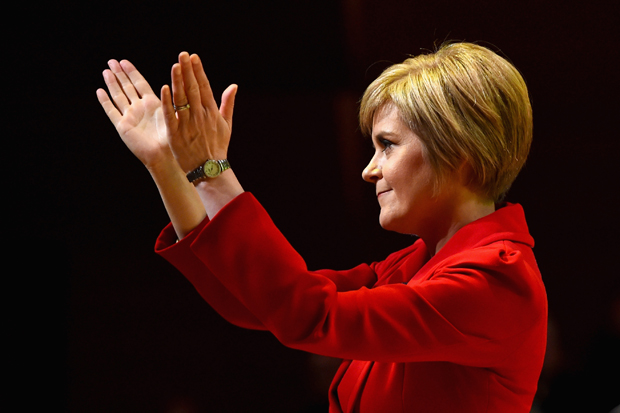

‘She sold out the Hydro arena faster than Kylie Minogue,’ said one awestruck unionist of Nicola Sturgeon this week. Scotland’s new first minister has come into office on a tide of support that many in Westminster find hard to imagine. Not only is she packing out concert venues, her party is also consistently scoring above 40 per cent in the polls. If she can keep this momentum going, she will rout Scottish Labour at the next general election.

Defeat in the independence referendum has not halted the nationalists’ momentum — quite the opposite. The party stands on the verge of an electoral breakthrough that few would have thought possible even three months ago.

Yet again, Westminster has read Scotland wrong. During the referendum campaign, one of the most influential Scots in the government told me that failure in the referendum would cause the SNP to descend into chaos. The nationalists would end up divided between those who wanted to settle for beefed-up devolution and those who wanted to keep on pushing for full-blown independence. This is what Labour thought would happen when it created the Scottish Parliament in 1999 — but then, as now, the enemy emerged stronger.

Sturgeon’s achievement is all the more striking because she is becoming first minister in a coronation rather than a contest. She has managed to captivate the public by her mere procession to Bute House. In contrast, Scottish Labour is struggling to get voters interested in its leadership battle, despite it being a dramatic choice between a sharp move to the left under the MSP Neil Findlay or becoming a reformist party under the Blairite MP Jim Murphy.

The new first minister is not a pint-swilling populist nor a shooting star of a politician. She has been deputy first minister for seven and a half years, part of a decade-long double-act with Alex Salmond. Those activists snapping up tickets to see her at the Hydro will have seen her on television for years. Unlike Salmond, a successful RBS economist before being elected to parliament, Sturgeon is a career politician with few outside interests. She became involved in SNP politics at 16, first stood for a Westminster seat at 21, became a member of the Scottish Parliament aged 28 and is married to the chief executive of the party she leads.

Will this wave of popularity for Sturgeon and the SNP break? Many on the Labour side argue that all Scottish polls will be fairly meaningless until it has selected its new chief (likely to be Murphy). But the worry for Labour is that, however popular their new leader is, a general election campaign will focus on Ed Miliband who appears to be as reviled in Scotland as Sturgeon is popular. The most recent poll there found that 59 per cent of Scots distrust him, compared to 29 per cent who trust him.

With Labour in disarray, Sturgeon — a Glasgow MSP and far more of a conventional social democrat than Salmond — is aiming squarely at the Labour vote in the West Central Scotland. In her first leader’s speech, she tried to claim from Labour the mantle of being Scotland’s ‘economically and socially progressive party’. She repeatedly attacked Labour as part of a distant, out of touch Westminster elite. Indeed, her anti-Labour rhetoric mimicked how that party so successfully delegitimised the Tories in Scotland in the late 1980s and 1990s.

Labour still hope that their message ‘Vote Sturgeon, Get Cameron’ will resonate in a country where, as one shadow Cabinet member puts it, many voters remain ‘neuralgic’ about the Tories. But, as the Tories are finding with recent converts to Ukip, it is hard to persuade people to vote for nurse for fear of something worse. Labour is also a noticeably less Scottish party than it used to be. In 1997, seven members of the Cabinet were Scots. Now, only two members of Miliband’s top team sit for seats north of the border.

The SNP might never, as Sturgeon says, enter into a pact with the Tories, but if they stick to their current position of not voting on English-only matters this would help the Tories considerably. For it would significantly reduce the number of MPs that the Tories would need to steer health and education reforms through the Commons. This advantage will become more pronounced as more responsibilities are devolved to Scotland. The Tories are, for reasons of both principle and politics, determined to cede a significant number of new powers to Holyrood.

The one thing that is certain is that, at the next election, the SNP will have a ground operation the likes of which we have not seen for many years. The party’s membership has increased by 200 per cent since the referendum and the SNP calculates that its membership extends to almost one in 50 Scottish adults — making it over three times more popular in Scotland than any party is in England.

Labour and Tory researchers at Holyrood are currently crawling through Sturgeon’s record as Scottish health secretary. They suspect that the hand-to-mouth nature of the SNP’s first years as a minority government means that there were some decisions taken which were short-term wise but long-term foolish. But the uncovering of a few bad calls is unlikely to be enough to knock the gloss off Sturgeon.

Those who imagined that the referendum would secure the Union for a generation have been confounded by recent events. If Sturgeon wins an overall majority at Holyrood in 2016, she may well go for a second referendum — and this time the nationalists would start within touching distance of victory.

For unionists, however, there is one consolation about the SNP’s surge. If they do end up winning a considerable number of seats in the Commons, then Westminster will have to be far more alert to what is going on in Scottish politics. There can be no repeat of the post-devolution ignorance and neglect that earlier this year so nearly ended the United Kingdom.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in