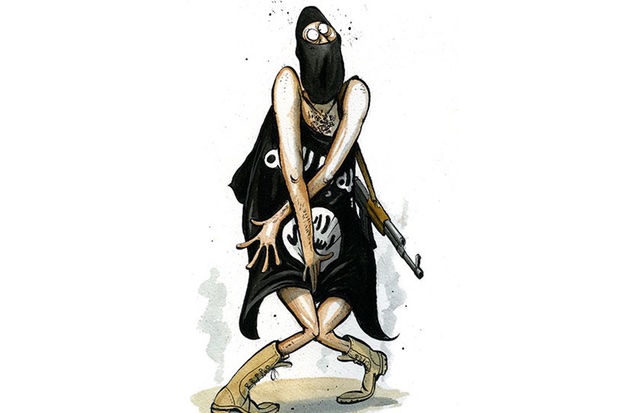

Turkish/Syrian border

It was Abouday’s heavy metal T-shirt that started the trouble. Two jihadis at a checkpoint said the fire-breathing dragon showed he was a devil worshipper. In fact, he worshipped only Metallica, but he did not realise the danger he was in. People had scarcely heard of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria back then.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

Paul Wood is a BBC correspondent covering Syria.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in