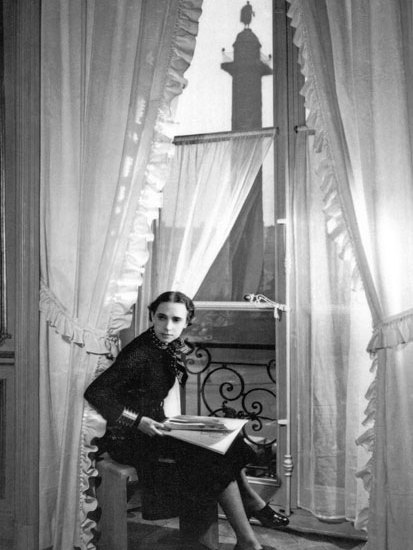

A comet streaked into France in the 1930s, its fallout sending the staid echelons of haute couture into a tailspin. A mere 30 years later a rogue missile blasted into London, blowing dainty English clothes sense to smithereens. Both these thunderbolts shot the stuffing out of cloying conventionality, one with an arrow-narrow silhouette, the other by blitzing the luxe out of luxury, the ex out of exclusivity.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

Elsa Schiaparelli, £20 and Vivienne Westwood, £22.50 are available from the Spectator Bookshop Tel: 08430 600033. Nicky Haslam’s memoir A Designer’s Life will be published later this month.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in