There are many more than seven killings in this ironically titled novel — in fact very long — that starts off set in the Kingston, Jamaica, of the 1970s, amid an efflorescence of political violence. The two major parties, the right-wing Jamaica Labour Party and the left-wing People’s National Party, were pouring guns into West Kingston’s slums to create loyal voting ‘garrisons’, controlled by neighbourhood dons — because ‘who-ever win Kingston win Jamaica and whoever win West Kingston win Kingston’, as one of Marlon James’s characters explains. The CIA was siding with the JLP, or, as another character puts it, ‘squatting on the city, its lumpy ass leaving the sweat print of the Cold War’. In any case, ‘killing don’t need no reason’, the first continues (he’s very much involved in it all): ‘This is ghetto. Reason is for rich people. We have madness.’

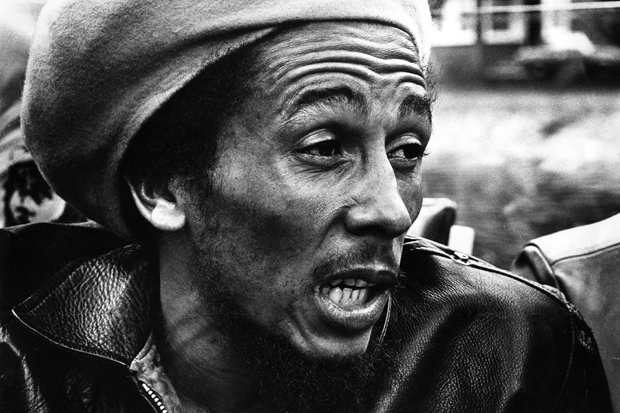

The mini civil war had two collateral effects that form the basis of James’s plot. The first was that it entangled Bob Marley, after he tentatively lent support to the PNP and also continued to rub shoulders with dons of both factions (the novel has him as a passive, almost Christ-like emblem of an abortive peace movement; he is referred to only as ‘the Singer’). On 3 December 1976, carfuls of heavily armed men invaded Marley’s home and showered him and his entourage with bullets, failing through some miracle, or narcotised teenage ineptitude, to assassinate him. The second development was that certain Kingston ‘posses’ inevitably outgrew their political masters, went freelance and exploded into the cocaine trade on the US east coast — which is the setting for the second half of the novel.

Twelve characters, half of them Kingston gangsters, take it in turns to narrate chapters, from the successive vantage points of five specific days between 1976 and 1991. Some are notionally addressing themselves — plaintively, resentfully, adoringly — to ‘the Singer’; several narrators perform in Jamaican creole, which is interestingly modulated in two ways. It is mainly rendered with English spelling, the usual method for extended narrative prose (the first experiment of this kind was Victor Stafford Reid’s New Day, published 1949, an historical novel set in the preceding pre-independence epoch, from which James’s book can be seen to take up the baton). It then shifts for reported speech to a thicker, phoneticised register, akin to that used in Jamaican poetry since Claude McKay (‘Still all dem little chupidness/ Caan tek away me lub…’; 1912) and for dialogue in prose fictions such as Roger Mais’s tremendous Brother Man (1954).

Where A Brief History might be breaking new ground with creole is in the ‘code-switching’ that some narrators engage in, dropping in and out and oscillating between various stations on what’s known as a ‘creole continuum’ — that is, sometimes nearer to and sometimes further from Standard English, according to the context and their distance, emotional as well as geographical, from the homeland. In this respect of voice it is a very fluid and superbly controlled work. The main non-Jamaican characters are Americans, also with their own effective argots: a rock journalist, a CIA agent and a wonderfully jaded hitman (‘I was about to shoot a rat in the bathtub, that’s how much I was bored when I got the call’).

The novel’s flaw is a lack of adventurous descriptive or atmospheric writing. The interior monologues are too tightly organised; the narrators spend too much time gnomically explaining the changing dynamics of the plot, their feelings or the historical background. There are exhilarating flashes here and there — a mugger ‘popping out of the alley wall like him was a jigsaw piece’ or ‘Rudeboys bodies bursting like pricked balloons, fifty-six bullets’ — but not enough of simply being allowed to see the world through a character’s eyes.

This makes A Brief History feel sterile in comparison with the full sensory experience of reading Faulkner, in many ways James’s most important model, or indeed V.S. Reid (‘Thunderhead for day-cloud and the sun peeping though blackness on grey water in the Bay, so is Davie’s eyes’). But it may be that there is a philosophical reason for James’s restraint, articulated by another character: ‘West Kingston… it so ugly it shouldn’t produce no pretty sentence, ever.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.99 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in