Turkey, Syria

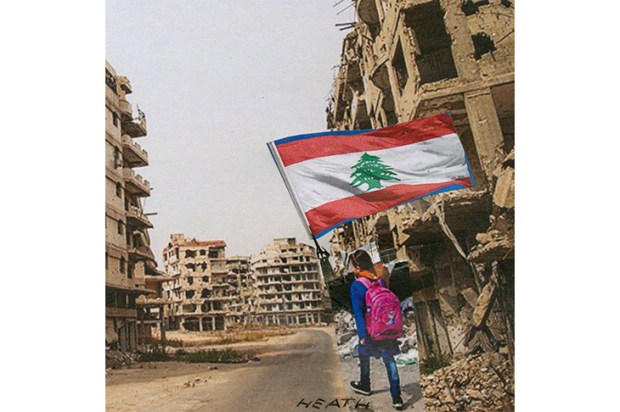

It is the early hours of the day that Parliament votes on whether to bomb the so-called ‘Islamic State’ — and we are sitting cross-legged on the floor of a Kurdish smuggler’s house. He has a picture of Mecca on his wall, a gold watch on his wrist, and an open bottle of whisky by his side. His main business is running guns — we are offered a Beretta pistol for $1,000 — but last night he smuggled 70 cows from Syria into Turkey. We want to go the other way, into Syria and the Kurdish town of Kobane, which is under siege by IS. Our plan is already in trouble, because of the cows. Turkish soldiers watching the border are usually bribed to look the other way, the smuggler explains, but this time their officers could hear something was up. The way in is closed. Loud mooing comes from the darkness outside.

Our smuggler drinks steadily and holds forth on the Kurdish tragedy. We have always been surrounded by enemies, he says. The wars in Syria and Iraq will end in another Sykes-Picot, the Anglo-French treaty that carved up the Ottoman empire after the first world war. The Kurds will get shafted again. Turkey’s ‘Kurdish problem’ certainly does not help the campaign against IS. The Kurds holding out — just — against the jihadis in Kobane are from a militia called the YPG, brothers-in-arms to the PKK, which fought the Turkish state for 30 years. The Turks are nervous about the 140,000 refugees the UN says have crossed from Kobane so far. The Kurds, for their part, accuse Turkey of fostering IS, letting volunteers, money and guns cross the border. A Turkish journalist tells me there are still IS safehouses in the country. There is also the mystery of how Turkey managed to secure freedom for 49 of its citizens held by the jihadis in Mosul. Now that the hostages are free, though, the Turkish parliament will debate military action against IS.

Despite the lack of financial arrangements, we try the border at noon. They throw a plank over the razor wire and a YPG fighter takes my arm to keep me on a narrow line of footprints in the dust. ‘Mines,’ he says. On the other side, families huddle in the desert, people turning their faces away from a sand storm. Nearby, Kobane is shuttered and empty: the Islamic State are now just three miles away. We are taken to see a stretch of road the Kurds recaptured the day before. The tension in the car is sickening as we drive away from town. A hundred yards ahead, a shell crashes down in a field next to the road, setting the grass on fire. Fighters crouching in a large, sandbagged hole wave us over. The light is fading; it’s nearly time for the nightly jihadi offensive. Bullets whine overhead. Seeing the fear on my face, an old man with a Kalashnikov puts a comforting arm around me. He looks up at the sky and points. I assume he hears American planes but he says simply: ‘God is real.’

While we’re there a text comes through that the Commons has voted to join the bombing. This is only in Iraq, so far. Syria may come later; Syria is complicated. The Syrian Kurds, though poorly armed, are a unified force capable of acting as infantry to the American planes. But further west, in Arab areas, there are hundreds of armed groups, most of them Islamist and many sympathetic to the jihadis. Syrian activists have taken to listing the civilian casualties they say resulted from the coalition’s airstrikes next to deaths from the regime’s barrel bombs, as if the two are morally equivalent. ‘This is Crusader-Arab treachery,’ said one placard at a protest against airstrikes, ‘a war on all Sunnis.’ Several rebel brigades issued a statement accusing the West of inventing a terrorist threat to carry out strikes, adding to Syrian suffering. ‘This is another example of the West’s hypocrisy,’ it said. Some of those signing the declaration were part of what used to known as the Free Syrian Army. For all practical purposes, the FSA barely exists in much of rebel-held Syria. The US-led coalition’s air campaign will struggle to find a reliable partner on the ground. No wonder the politicians warn of a long war.

We try to head back over the border after dark. But hundreds of Turkish Kurds have crossed into Kobane during the day for a solidarity march. They are trying to force their way back into Turkey and are met with volleys of tear gas, then live rounds. One man is shot dead, another wounded, another beaten unconscious with rifle butts. Admittedly, the man shot dead was wearing a camouflage jacket and might have been mistaken for a fighter by the Turkish troops. Regardless, there will be no crossing tonight. Instead, we go to edit our piece at the hospital, one of the few places with electricity. A Kurdish politician tweets that IS are less than a mile from Kobane and the town will fall by morning. We can’t hear gunfire and the politician has been accused of exaggerating in the past. Still, we’re getting reports that IS fighters are being withdrawn from other towns they hold to attack Kobane. We decide to move to a building overlooking the Turkish military checkpoint. This means swapping the hospital’s comfortable beds for a concrete floor. But we don’t want to wake to find the jihadis between us and the border.

We wake, a little stiff, to the sound of planes flying overhead, but otherwise Kobane is quiet. There were American airstrikes overnight, the first here. The Kurds held IS back at the place we had been the day before. There is more good news. Our producer on the Turkish side, doing what she calls her ‘dumb blonde act’, has managed to charm the border guards into letting us through. Later, it turns out there were only three US airstrikes — not nearly enough to save the town, say the Kurds, angry and disappointed. We stand on a Turkish hillside and watch Islamic State mortars fall on Kobane. A cloud of smoke and masonry dust hangs in the air for a minute. It is gone by the time we turn to head for the car.

The Spectator is holding a debate ‘Iraq and Syria are lost causes: intervention can’t help’ at 7pm on Wednesday 22 October at Church House, SW1. Speakers for the motion will include John Redwood and Patrick Cockburn, and against, Douglas Murray, Ed Husain and General The Lord Dannatt. Chairing the debate will be Andrew Neil. For tickets and further information, click here.

The Spectator is holding a debate ‘Iraq and Syria are lost causes: intervention can’t help’ at 7pm on Wednesday 22 October at Church House, SW1. Speakers for the motion will include John Redwood and Patrick Cockburn, and against, Douglas Murray, Ed Husain and General The Lord Dannatt. Chairing the debate will be Andrew Neil. For tickets and further information, click here.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Paul Wood is a BBC correspondent.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in