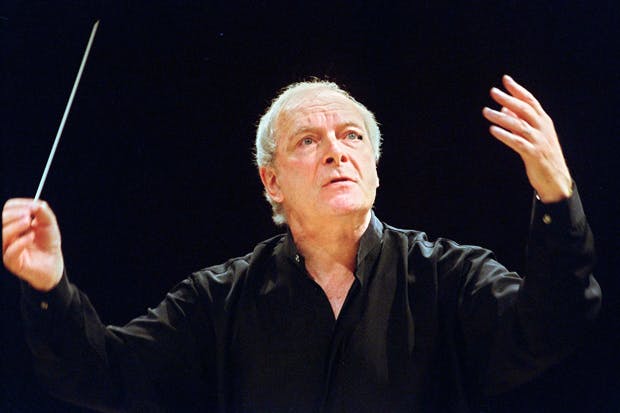

The death of Christopher Hogwood has deprived the world of the most successful exponent of early music there has ever been, or is ever likely to be. It has also reduced by one the quartet of conductors who have been called ‘the Class of ’73’, a term coined by Nick Wilson in a recent study of the early-music revolution of the 1970s and 80s. It refers to four groups that were founded in that year that are held to have changed the face of modern concert-giving: Hogwood and the Academy of Ancient Music; Trevor Pinnock and his English Concert; Andrew Parrott’s Taverner Choir; and my own Tallis Scholars. Of these it was Hogwood who had the most immediate impact and commercial success. It is also fair to say that his recordings are the most numerous, but least played, of all the Class.

Hogwood was a perfect example of being the right person at the right time. When he started the Academy in 1973, the major record labels of the day had been recording the centrepieces of the classical repertoire for a very long time in much the same way. Suddenly, thanks to Hogwood, the sound dramatically changed: gut strings rather than steel for the violins, fortepianos instead of Steinway grands, valveless brass instruments, little or no vibrato. And equally suddenly, this was what the public wanted: a crisper, lighter sound.

Hogwood’s vision of absolute authenticity — doing everything just as the composers would have done and heard it — was a dogma that carried all before it. The spirit of that age seemed to need such absolutes. It was no good admitting, as some early musicians did, that in fact one couldn’t get it all right and that to a considerable degree one was ‘making it up’ — to do that was to ask for rejection. Although Hogwood was called ‘a charismatic musical pirate’ at the time, he stuck to his principles. He was a considerable scholar, so it was hard to gainsay him.

By 1978 Hogwood and the Academy had started to record the complete Mozart symphonies, a project that was completed in 1985. This was by far the most substantial project of its kind. It still stands as the event that launched the early-music revolution, though for a time it was his 1985 recording of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, vying with Prince’s Purple Rain at the top of the pop charts, that caught everyone’s attention. For many people today, however, the most important recording of all was his 1980 Messiah.

Here was an iconic work, remade in a new/old image, which showed at a stroke that the traditional way of performing it was just not good enough. To use a cathedral choir of boys and men (Christ Church, Oxford) for the choruses was novel indeed (farewell, Malcolm Sargent and the Huddersfield Choral Society), but Hogwood also brought together a team of soloists at the top of their game — Judith Nelson, Emma Kirkby and David Thomas among them — who would dominate the scene for years to come. Recordings poured out of him — more than 300 are listed. The invention of the CD in 1982 was another piece of good fortune.

The Class of ’73 have gone their different ways. The heat of the early-music revolution was always in period instruments, which could so easily be shown to make a different sound from their modern equivalents. The same could not be done with voices, since we will never know what they sounded like in the distant past. So the Tallis Scholars have had a slower-burning career, though in its own terms no less revolutionary; while the English Concert have followed much of the path set out by Hogwood’s Academy.

Yet it is Hogwood’s star that has waned most decisively. Mistrust of absolute certainty in recent years — not helped by our politicians — has led to the feeling that Hogwood’s results were too academic, too dry. The good things that had come out of the revolution were subsumed into the methods that more recent, livelier original-instrument ensembles such as the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment employ. On the other hand, conductors such as John Eliot Gardiner — always too cautious to be in the vanguard — proved more durable simply by not sticking their necks out. And Hogwood’s ideas can be said to have affected the classical performing world even more fundamentally: the public no longer welcomes wide vibrato in any field, modern orchestral playing or operatic singing. A big wobble is no longer trendy.

In correspondence Hogwood liked to sign off with the word ‘sempre’. I liked it because I knew he meant it. And it looked for a long time as though it might be true.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in