John Gerard, a Jesuit priest immured in the Tower of London in 1597, and tortured by being hung from manacles until he temporarily lost the use of his arms, was a resourceful as well as courageous fellow.

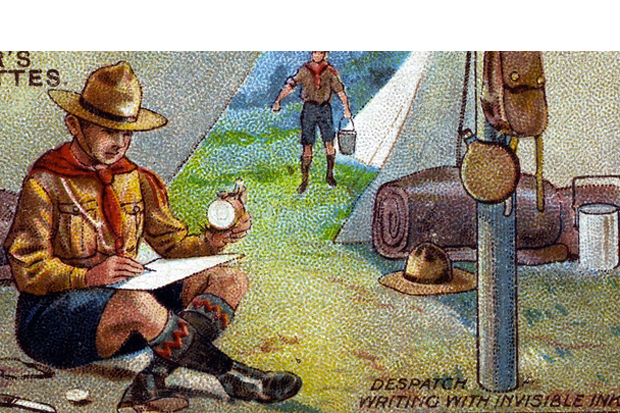

Dependent on the kindness of his jailer, a warder named Bonner, for such intimacies as washing, dressing and shaving, Gerard also persuaded the turnkey to bring him a bag of oranges. Regaining the use of his hands, he employed the fruit for two purposes: to fashion crosses and rosaries from the discarded peel, and to make invisible ink from the juice.

Using this secret script, and writing with a toothpick, Gerard made contact with Catholic co-religionists outside the Tower’s walls, and arranged for them to ‘spring’ him and another imprisoned Catholic, John Arden, in one of the Tower’s most spectacularly successful escapes. Warder Bonner, converted by the force of Gerard’s personality, joined his former charges on the run.

This benign use of secret writing is just one of scores of similarly entertaining stories told by the American academic Kristie Macrakis in her beguilingly informative and sweeping survey of hidden communication from the classical world to today’s al-Qa’eda terrorists, who use un-Islamic porn to conceal their murderous messages in microdots.

The libidinous Roman poet Ovid was long thought to have made the earliest surviving written reference to invisible ink in his manual The Art of Love. He recommended young lovers to use ‘new milk’ made visible with a sprinkling of coal dust, as a sure method of keeping secret amours safe from prying eyes.

Macrakis, citing Herodotus, shows that secret writing was particularly favoured by the Medes and Persians. A revolt by Greeks living under Persian rule in Miletus on the Ionian coast, for example, was triggered by an illiterate slave sent to the town with a message that the time was ripe for a rising tattooed on his skull and hidden by his growing hair. As Macrakis dryly remarks,

In addition to the weeks needed for the slave’s hair to grow, the trip on foot to the coast must have taken at least three months, but what the plan lacked in urgency it made up in effectiveness: the revolt was a success.

Herodotus also claims that Persia’s Cyrus the Great owed his remarkable rise to a secret message that the Medes were ready to overthrow their king and defect to him. Secreted on a tiny scroll, this intelligence was concealed in a location even more unlikely than on a slave’s skull: in the belly of a hare, which Cyrus was instructed to slit open to read his illustrious future. Proving that there’s nothing new under the sun, Macrakis says that the CIA hid microfilm inside dead rats, while Chinese emperors wrote missives on silk, which were rolled into small balls and slid up the rectums of their servants.

Apart from Ovid’s homely milk and the juice of citrus fruits as used by Gerard, human bodily fluids — Churchill’s blood, sweat and tears (and saliva and urine) — have been utilised down the ages to transmit covert information. In the 1920s, says Macrakis, male MI6 agents were instructed by their original chief, ‘C’, the eccentric but effective Mansfield Cumming, to experiment to see whether semen could do the same trick.

According to Macrakis, the ‘ink’ produced by spies masturbating in the office to order worked well enough as a ‘one time pad’, but attempts by one over-enthusiastic spook to store his excess seed for future use were a failure, resulting in what Macrakis calls distinctly ‘stinky ink’.

It was the unpleasant odour given off by a solution of sulphur, quicklime and ammonium chloride that caused the 17th-cen-tury scientist Robert Boyle to be suspected of attempting to summon the Devil, when in fact he was trying to perfect a secret ink after his experiments with urine and blood serum had produced only partially satisfactory results.

Secret writing and its detection reached its apogee in the two world wars when all the combatant nations employed thousands of people in steaming open private mail to search for concealed messages. One spy who fell foul of such state snooping, and whose brief stay in the Tower in 1915 did not have such a happy ending as John Gerard’s, was Germany’s Carl Muller, an agent who wrote his reports in old-fashioned lemon juice between the lines of his innocuous letters. Apprehended by Scotland Yard with a tell-tale lemon in his pocket, Muller was shot by firing squad in the Tower’s moat. The fatal lemon — black and withered after a century — is preserved in the National Archives.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.99. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in