Democracy in ancient Athens was often criticised by the aristocracy for not showing significant respect for them and their superior qualities. However, it was Socrates who came up with the most novel critique of democracy; its primary defect lay in giving power to the ordinary citizen rather than the technical expert. In the Republic Plato took this idea to its logical conclusion by constructing a state whose members were allocated to their roles according to their talents.

Like the Athenians the modern West has moved from aristocracy to democracy, and like them we have those who see their expertise as qualifying them to be the new aristocracy. One thinks of scientists and economists and the lawyers, especially the lawyers.

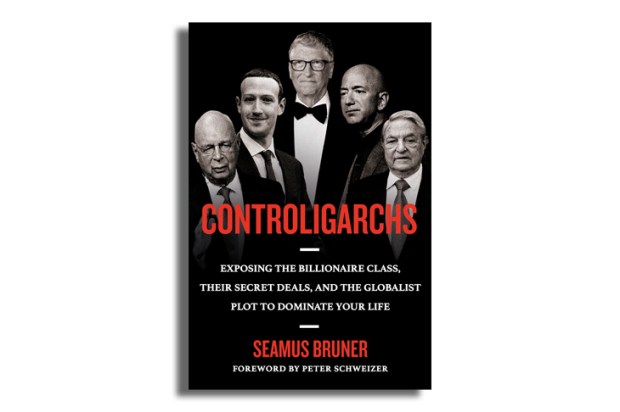

James Allan’s new book is essentially an extended warning against allowing lawyers, especially former lawyers who have become judges, to take away the capacity of democratically elected governments to legislate on certain matters and assigning it to themselves. There are a number of means through which they do this, including international treaties and international law, but the primary means is the establishment of a Bill of Rights.

Allan is only concerned with the long established democracies of the Anglophone world, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. He argues that in each of these countries democracy, understood in terms of deciding matters through the majority vote of the legislature, has declined over the past 30 years. The reason for the decline has been the transfer of decision-making for many matters from the legislature to the courts and the primary reason for this transfer has been the introduction of a Bill of Rights.

The worst case has been the United Kingdom which has been hit by both a Bill of Rights and all the rules and regulations imposed on it through its membership of the European Union. The best case is Australia, primarily because it has refused to institute a Bill of Rights, making it the last common-law democracy in the world.

What then is the problem with introducing a Bill of Rights? After all, surely a Bill of Rights is designed to protect the rights of the citizens of a democracy. The real problem is that it removes the capacity of the legislature to make decisions over certain matters and hands them over to unelected judges. These judges invariably hold to ideas which are out of sync with the wider population.

Take one example: in Australia it is up to the legislature to make the law on such matters as abortion. In the United States the Supreme Court decides, as can be seen in Roe v. Wade. Allan’s basic argument is that in a democracy such matters should be determined by the people’s representatives. If you win, you win, if you lose, you lose, but the decision has a legitimacy attached to it which it doesn’t if it is made by an unelected court.

Here we are left with a paradox: the idea of human rights was introduced with the best of intentions, but its consequences have not measured up to those intentions. Why has this been the case?

One reason is that, in retrospect, it can be seen that the idea of such rights is inappropriate in mature democratic countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia. Rights appeared in the history of the West as a protection against the excesses of state power. They were originally designed to prevent the monarch from harming his citizens. The Americans introduced their Bill of Rights in the wake of a war in which they saw George III as having abused their rights as Englishmen.

However, for a long time other Anglophone countries saw no need to emulate the Americans. They knew that their laws protected them. The revival of human rights came after the second world war, in reaction to regimes which had abused the people under their control. Individuals needed protection so that this never happened again.

Since that time human rights have become something of a fetish, although it can be argued that appealing to human rights is useful in those parts of the world where governments operate with unrestrained power. The world of English-speaking democracies is not part of that problem. They protect the rights of their citizens well, just as they always have.

Why then have all of these democracies, with the exception of Australia, decided that they need a Bill of Rights? Allan does not really discuss this matter. He is more concerned with the consequences of introducing them. They have enhanced the standing of the legal profession and turned it into a sort of aristocracy. Power has been transferred from the people to an unelected group.

Moreover, as Allan constantly demonstrates, this group is relatively unconstrained in the way in which they interpret the meaning of these rights. It is not the words on the page which matter but, because there is a ‘living constitution’, the so-called state of civilisation in which the judges are living. In other words human rights mean what the judges say they mean.

Essentially judges have made their claim to be the new aristocracy based on the possession of their arcane knowledge of the law. They know what is in the best interest of individuals rather than individuals themselves. They have established themselves as the new guardians.

Australia has been fortunate to escape the worst of these developments. Australians have no desire for a Bill of Rights. But it has not escaped unscathed as there are judges in this country who would happily clamp the chains of human rights on us.

The irony here is that human rights were designed to protect us from government excess, but their consequence is to take power away from the people and place it in the hand of the new would-be legal aristocracy. In such a world who, and what, will protect us from the potential despotism of this new class of guardians?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Greg Melleuish is associate professor of history and politics at the University of Wollongong. He is the author of, among other books, Cultural Liberalism in Australia and The Power of Ideas: Essays on Australian History and Politics.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in