‘Phlogiston’ is an interesting, if obsolete, word. Of Greek origin, it referred to the ‘fire-making’ quality thought to be present in, among other things, the ashes gathered by London dustmen. In the mid-18th century these ashes were mixed with earth and even ‘excrements taken out of the necessary houses’ to create the vast numbers of bricks needed for the explosion of house-building taking place at the time in London and elsewhere.

The dramatic rise in building is pivotal to this densely detailed observation of the British obsession with their ‘home’ and ‘comfort’ which, we’re told, Robert Southey describes as particularly English and untranslatable.

The first third of this trivia-packed and fascinating miscellany sets the scene for the ‘haves’, living in castles, stately homes or Vince Cable’s ‘mansions’, and the ‘have nots’, occupying cottages, with less of the romantic and more of the squalid. Medieval hovels and castles, and their origins, are chronicled with efficient briskness, with the ‘statelys’ more or less brushed aside since, as Philippa Lewis points out, they have been described and photographed far too frequently. But Lewis warms to her theme as the 18th century moves into the 19th with the concomitant industrialisation, expansion, emancipation and mobility.

Unashamedly riddled with class from beginning to end (unavoidably, considering national aspirations and class mobility, both upwards and downwards), the joy is that Lewis has produced a stream of commentary culled from an astonishing range of literary references interwoven with hard facts. Liberally scattered with the rewards of wide-ranging picture research throughout, it’s a very handy-sized volume, the text a mere 250 pages.

Focused on London, the practices — and differences — in other parts of England, and just now and then, Ireland and Scotland, are mentioned, with comments on slums, philanthropy and council housing. One paragraph can range from the desirability of the inglenook as central to cottage life through the Grand Tour to the welcome introduction of plumbing in a great house, commenting, in passing, on the reckless extravagance of the ‘mansion’ builder and the consequences for his heirs. But it’s urban living in all its guises that really piques Lewis’s interest. Terrace-building is scrutinised, accommodating servants bottom and top. ‘Top-shops’ were the workplaces of the silk weavers, crammed, sweltering, into attic spaces for the best light. The great levelling system, the tenement, so beloved of the burgeoning Scottish metropolises, gets a nod and is perhaps the blueprint for flats and apartments, developed later in England than elsewhere. Ironically, in flat-land, top is best.

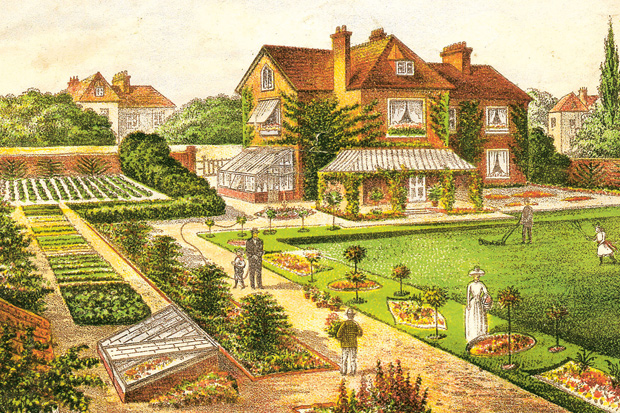

At a time when it’s hard to imagine how future generations will ever attain the ubiquitous English goal of homeownership, this is nostalgic Arcadia. The 1905 ‘Cheap Cottage’ exhibition at Letchworth, Hertfordshire (brainchild of J. St. Loe Strachey, the then editor of The Spectator), was a fore-runner of Garden City planning, and promoted ‘cottages’ that could be built for £150. It showcased new ‘wonder’ building materials (including asbestos cladding). Metroland beckons, and Lewis’s gleanings are particularly good on the subtle but significant move from boarding house to bedsit, a mid-20th century phenomenon. She cites that infamously self-promoting 1960s Chelsea estate agent Roy Brooks, an unwittingly useful source of comment on gentrification. An advert, illustrating a husband carrying his bride over a threshold juxtaposed with him carrying a ‘Leisure Vogue Room Heater’ over the same threshold, epitomises the rosy-hued optimism of 1964. Nowadays one would be nervous of the former and he is unlikely to do the latter.

Lewis cannot possibly cover it all. The rise and fall of dockland supremacy, the influence of immigration, expansion of dormitory towns — these are omitted. Habitat, Ikea, the Candy Brothers and Kevin McCloud’s Grand Designs are not referenced, although we are reminded of the latter’s sustainability property company HAB — ‘Happiness, Architecture, Beauty’. And so it is. This book is exactly what it says: a paean to the British passion for their very own ‘castle’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in