Published to mark the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Vercors, perhaps the most famous stand of the French Resistance in the second world war, there is an awful inevitability to this book. Tragedy looms like the great plateau itself, overshadowing the individual stories of the people who lived, fought and died in these mountains. The strategic and tactical failings that led to their defeat run like strata through the history: a lack of clarity in Allied communications; failure to deliver sufficient heavy weapons or reinforcements; the mistaken use of a guerrilla army as a fixed, defensive force and, above all, the tendency to let diplomacy and politics trump military common sense. And yet Paddy Ashdown has produced not only the most thorough history to date of the Resistance in the Vercors, but also the startling new contention that, ‘the Germans did not win on the Vercors. They lost.’

Essentially this is military rather than social history but, in the Vercors, the military and the human coincided. The Vercors resisters included Catholics, Jews and communists, career soldiers, farmers, mechanics and civic leaders. Some of the men lived on the plateau for two years; others ‘went to war still in the clothes they had left home in two days previously’. Often all that united them was the depth of their convictions, and their love of free France. As Ashdown notes, ‘not all were brave, and not all died well’, but many, too many, died.

To explain why, after some scene setting, time slows down as chapters, initially dedicated to months, are reduced to ‘The First Five Days of June’, and then to single days of July. Written with pace, the detail is fine, but the pain of watching radio signals repeatedly ignored, lessons unlearned in the field, and opportunities consistently missed at the highest levels becomes almost unbearable.

Fortunately the cast provides plenty of colour. An ‘excitable sentry’ raises the alarm when facing attack by what turns out to be a troop of foraging badgers. At Resistance HQ on the plateau, the arrival of a bomb during dinner prompts not flight but a rousing chorus of the Marseillaise. Various states of undress reveal an automatic pistol under a priest’s surplice and, according to one harassed but patriotic café-owner, pulling up her skirts, the appropriate place to search for partisans, about whom she has already denied all knowledge.

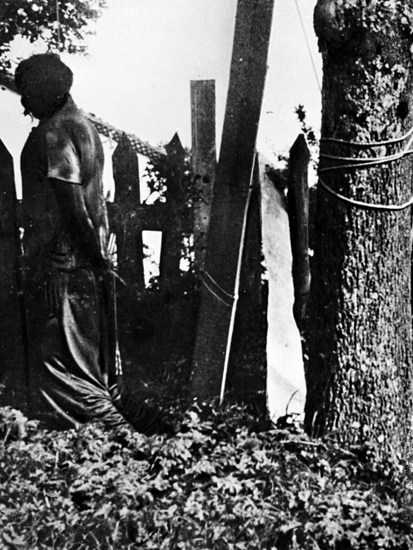

There are also moving domestic details, inspirational accounts of bravery, brilliant command, occasional mercy and good fortune, and the necessary but appalling stories of the retributions and atrocities that marked the end of the Free Republic of the Vercors. Two sounds, Ashdown notes, characterised these last days, ‘the screaming of unmilked cows and the rattle of the machine guns floating up from the valley below’.

Ashdown is well-placed to write this book, which requires an understanding of military strategy, diplomacy and political shenanigans, as well as old-fashioned story-telling skill. However although he argues compellingly that the Germans were not successful in their strategic goals in the Vercors, it does not necessarily follow that the French won even a ‘cruel victory’. There is no questioning the ‘raw courage’ of those who fought for what they believed was the liberation of their country, or the ultimate political value of the legend of the Vercors. In the final analysis, however, the action tied up relatively few battle-ready German troops, displaced potentially more valuable ambush and sabotage operations, and led to the perhaps unnecessary loss of 200 civilian, and over 600 maquisard, lives.

Arguably the value of the battle of Vercors lies in its simply having taken place, symbolising the French will to fight, and the sacrifices made during years of Resistance, rather than in its results. But like many actions that turn into legends, the Vercors has since been used to various political ends. The great value of Ashdown’s history here is not that it argues the toss on who won the battle, but that it provides an objective assessment of this extraordinary human epic, placing it within the wider context of Allied war strategy. In doing so it provides a fitting tribute to the many diverse individuals who came together to fight for a free France 70 years ago this summer.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20. Tel: 08430 600033. Clare Mulley’s life of Christine Granville, The Spy Who Loved, was published in 2012.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in