Listen

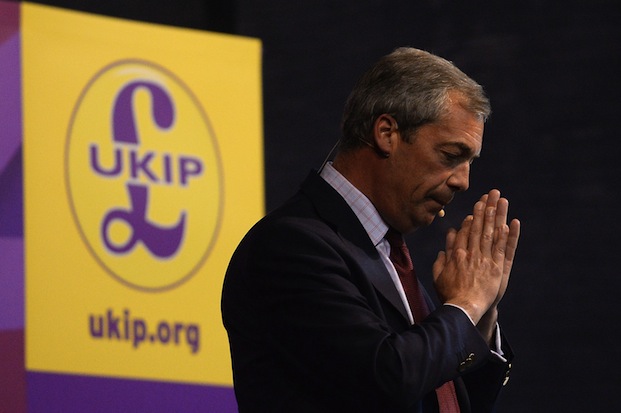

There are many words that you might associate with Nigel Farage, but moderniser probably isn’t one. Yet the Ukip leader is embarking on the process of modernising his party. He has concluded that it cannot achieve its aims with its current level of support. So he is repositioning it in the hope of winning new converts even at the risk of alienating traditional supporters.

If this sounds similar to what David Cameron did after winning the Tory leadership in 2005, that’s because it is. Interviewing Farage during his triumphant European election campaign, I was struck by how he talked approvingly of ‘New Ukip’, which he claimed had ‘gone past the hobby horse’ phase and had the discipline to target individual seats, unlike ‘Old Ukip’. It was reminiscent of how the Cameroons used to talk in the early days of his leadership or, going further back, how those around Tony Blair would boast of their transformation of the Labour party.

There is an irony here. Cameron’s modernising programme was one of the things that gave Ukip space to grow. The Cameroons assumed that voters on the right had nowhere else to go as they changed tack on a whole host of issues. But Ukip picked up a number of these people.

It has also adeptly tapped into local Tory discontent with coalition policies. ‘Do not underestimate the number of people in the English county elections last year who voted for us on the wind farm issue,’ Farage told The Spectator recently. ‘There are 310, I think, wind farm protest action groups in this country and every single one of them is talking to Ukip.’

Farage would not thank you for comparing his approach to Cameron’s; he prides himself on being different from the Tory leader. He is never going to be seen hugging huskies. But he doesn’t want Ukip to be just a home for disillusioned Tories any more. Instead, he wants it to reach out to working-class Labour supporters who feel alienated from its current leadership.

If this means Ukip losing some of its intellectual consistency, then that is a price that the leadership is prepared to pay. In Ukip’s struggle between its libertarian and blue-collar tendencies, it is the latter who are winning, as James Delingpole’s eloquent cry of pain on page 28 demonstrates.

But you can’t win parliamentary seats with just disillusioned Tories, and Ukip desperately needs representation at Westminster if it is to establish itself as more than a protest party.

Tellingly, the Ukip leadership now believes that its best chance of gaining a foothold in Parliament is in marginal seats where it can make inroads into the Labour and Tory vote. This means that the party has to be able to appeal to a chunk of those who traditionally back Labour.

Ukip did this with some success in the European elections, emphasising that immigration had held down working-class wages and that the only way to stop mass immigration from Europe was to leave the European Union. But those close to Farage know that come the general election, Labour will try to win these voters back by arguing that Ukip is a ‘Thatcherite’ organisation that wants to charge you for using the NHS and abolish your right to paid holiday leave. If the party is to have a chance of holding on to these new supporters, let alone reaching their compadres, it’ll have to be able to robustly rebut these claims.

Farage has no desire to give currency to the Tory accusation that a vote for Ukip is a vote for Miliband. He knows that this charge could well put off both voters and donors. One influential Eurosceptic fundraiser tells me that one of the things that keeps big-money prospects from giving to Ukip is a worry that they’ll be rollocked by their peers, who’ll attack them for paving the way for a mansion tax and the return of the 50p rate.

Farage, like Cameron, is putting his commitment to the NHS at the centre of his modernisation effort. His first aim is to reassure voters that Ukip is committed to the NHS. He knows that Labour will make much of its claim that Ukip would impose charges for visiting a GP. So expect to see Farage stressing Ukip’s commitment to a universal, free-at-point-of-use health service at every opportunity.

This is sensible politics. As a former editor of this magazine said, the NHS is the nearest thing modern Britain has to a national religion. Any politician who suggests radical reform risks being burnt alive as a heretic. But it is rather depressing that even the insurgents in British politics feel that they have to pay obeisance to the old rite. Sadly, Farage is no John Wycliffe.

Ukip also know that Labour will attack them for having backed a flat tax, which would mean rich and poor alike pay the same marginal rate. Farage, when he returned to the leadership in 2010, saw the obvious political and presentational problems with the policy and jettisoned it. But Labour will still use it to create questions about Ukip’s motives and its claim to stand for the working man. Tellingly, when Farage now talks about tax he’s quick to balance his desire to abolish the 45p rate with support for lifting everyone on the minimum wage out of tax altogether.

Even on immigration, Ukip’s trump card, Farage is fine-tuning the party’s position. He’s keen to show that he isn’t anti-immigration per se, but that he just wants it to be controlled and for Britain’s benefit. He boasts of how ‘there are some people within Ukip, as well, who have tried to portray us being an anti- immigration party and I think I’ve taken that away from them’.

Farage’s willingness to take on the hard task of modernising his party is another reminder that he is serious about turning Ukip into a permanent presence on the British political scene. He knows that he has to win seats at Westminster and is doing what’s necessary to achieve that. The challenge for him, though, is to do this without making Ukip seem like just another political party.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in