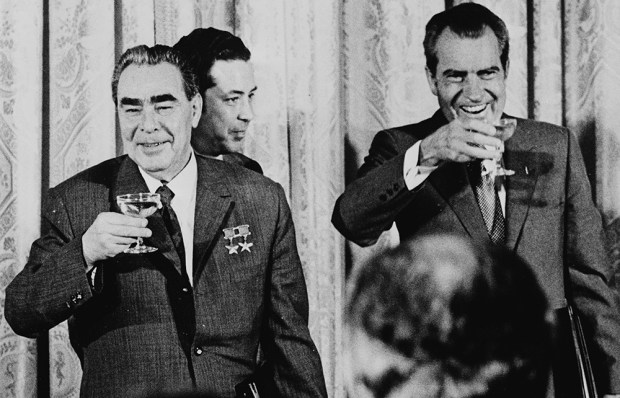

For some of you younger readers the name Schmuel Gelbfisz will not ring a bell. Yet back in the Thirties Schmuel Gelbfisz’s identity was a dinner-party quiz question, and the one who guessed correctly would receive a kiss from Mary Pickford — America’s sweetheart — if he happened to be a man, or an expensive trinket if a lady got it right. Schmuel was born in Warsaw, Poland, in July 1879, a Hasidic Jew, but later on falsified his birthday in order not to serve in the tsar’s army. He left my favourite country as a 16-year-old and walked to …Germany. He had no money and no friends, got to the Oder, fell into the water, was fished out by border guards, talked a good game and walked another 200 miles to Hamburg. When Gelbfisz died, in January 1974, President Nixon paid him a visit on his deathbed and headlines announced his passing. He was, of course, the last of the great independent producers of Hollywood, a giant of the industry better known as Samuel Goldwyn.

If Sheridan had not invented Mrs Malaprop, Goldwynism would be the word in the dictionary that identifies the misuse of language. I will give you just a few of them, having just read a magnificent biography of the mogul by Scott Berg, a very talented writer whose brother is a top Hollywood agent with whom I broke bread in Cannes last year following the premier of the greatest movie ever, Seduced and Abandoned.

Long after he had become fabulously rich and famous, Goldwyn would proudly show his art collection to his guests, always zeroing in on his ‘Toujours Lautrec’. When his wife suggested a friend seek psychiatric help, he interrupted with, ‘Anybody who goes to a psychiatrist should have his head examined.’ His most famous Goldwynism was ‘Include me out’, which he sprang on his board, which included Averell Harriman, a lifelong friend. Charlie Chaplin and countless others, including Douglas Fairbanks, claimed that they were present at the creation, such was the beauty of that particular malapropism. When a director complained about the lighting, Goldwyn told him, ‘You gotta take the sour with the bitter.’ His banker, who was complaining about overruns in the budget, he admonished with, ‘We are dealing in facts, not realities.’ When absent from his office, he told his secretary, ‘I’ve been laid up with intentional flu,’ and when some eager-beaver producers tried to hustle him into financing a project, he resisted them by telling them no, ‘I would be sticking my head in a moose.’ He was also the author of the all-time favourite, ‘A verbal agreement is not worth the paper it’s written on.’ Early on in his career, he warned his director that ‘this whole damned picture will go right out at the sewer’, and much later, when the grand Bill Paley took him shooting on his Long Island estate and told Sam, ‘Look at the gulls’, Sam answered, ‘How do you know they’re not boys?’

When he gathered all the musical talent in Hollywood, including Leopold Stokowski, George and Ira Gershwin and others, he told them, ‘All this modern music you like is so old-fashioned,’ and then pronounced that ‘Dostoevski would be his musical director’. ‘You mean Stokowski,’ said Vera Zorina, a great beauty Goldwyn was mad about. ‘No, I mean Dostoevski.’ Later on, when a writer tried to dissuade him from a certain depressing play and said, ‘Sir, it’s a very caustic play,’ Sam shut him up with, ‘I don’t care how much it costs, buy it.’ Finally, when the Gershwin brothers came to his house for a conference, Goldwyn, who had just learned the rudiments of American football, announced from the floor above that he would come down in a jiffy and the three of them could then ‘have a cuddle and decide’. The Gershwins burst out laughing and Sam always held it against them.

Goldwynisms were the talk of the town for 60 years and then some. Sam didn’t get along with the Marx Brothers and we can guess why. They were much too irreverent for a man who used his Norman Rockwell lens to filter and film America. He was wounded when Groucho, a fellow Jew, made his famous wisecrack about the disparity in the chest development of Victor Mature and Hedy Lamarr, playing Samson and Delilah in the Cecil B. DeMille epic. ‘Why is he making fun of prehistoric Jews?’ was the way I assume he would have put it.

Yet all those Mitteleuropa Jews did invent a Norman Rockwell America of white picket fences and naughty boys with bandages on their knees and smudges on their faces. Louis B. Mayer of MGM, Harry Cohn of Columbia, Jack Warner of Warner Bros, and Goldwyn invented America and made it a better place despite their personal failings. Harry Cohn was such an ogre that when he died in 1958 and a member of his family asked the rabbi if he could think of one good thing to say about him, the Rabbi Magnin answered, ‘He’s dead.’

Christian religious groups and civic organisations dedicated to cultural uplift felt that European ‘fatigue’ might undermine traditional American values. They were right, but 30 years too early. By the time all the moguls were dead, the untalented and very nihilistic had taken over. The F-word became a gerund and violence the norm, always a true sign of someone who, lacking talent, substitutes it with explosions and vulgarities.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in