This week, the European parliament took a strong lurch to the left. That is not quite the story that you may have read elsewhere — with most headlines stating that Europe has taken a lurch to the right — but it is the inevitable conclusion if you analyse the results from Sunday’s election from the perspective of what most people in Britain understand to be the left-right divide.

Take any political issue in Britain, from schools to public spending, and the left-wing position is generally taken to mean one of greater state intervention, greater command of the economy by government. The right-wing position is taken to mean one of smaller government, freer markets, less regulation. Why then, does a party like France’s Front National — which advocates protectionism and welfarism, and which opposes globalisation — end up being called ‘far right’?

If the Front National is far right, then the centre-right must be all about partial protectionism, a tendency to see welfare as a public good and to be a little suspicious of globalisation. Yet that all sounds more like an Ed Miliband manifesto. True, back in the 1970s Jean-Marie Le Pen once adorned his racist views with economically liberal ideas. But that is a long time ago. This week’s election marks the completion of a remarkable transition across Europe since the fall of the Berlin Wall: from Sweden to Greece, the nasty parties have, in important ways, become more far-left than far-right. The parties which triumphed this week are those which offer a perfectly logical combination of xenophobia, nationalism and state authoritarianism.

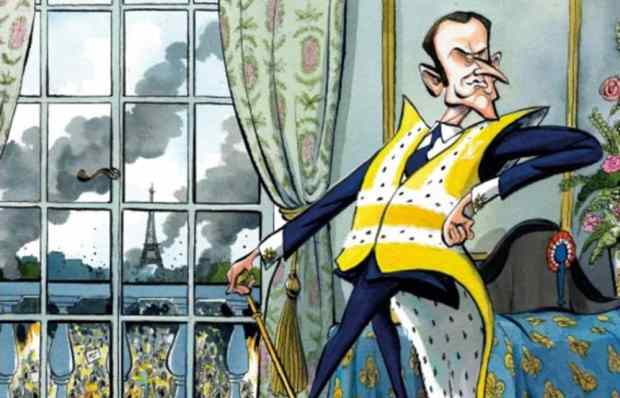

Perfectly logical, but profoundly wrong. While many of the representatives of global capitalism — bankers, tax-avoiding international corporations and so on — have turned out to have feet of clay, the greatest damage to economies has come from governments which tried to borrow their way out of a debt crisis, then tried to rig markets so as to re-inflate financial bubbles which kept their coffers full. The winners from quantitative easing and unnaturally low interest rates have mostly been the well-off, while a disproportionate number of the losers have been on low incomes. It is a recipe for greater in-equality.

It is not surprising, then, that the European elections saw a ‘peasants’ revolt’ against a political-economic machine accused of flattening the poor. But it doesn’t follow that we would be better off replacing one form of big government with another. Far better that we shrink government altogether and let the economy create more jobs than the government has shed — which is what has happened in Britain in recent years. This is not, however, a route which continental Europe seems likely to make in the near future.

Of 751 seats in the European parliament, only 46 — those held by parties belonging to the European Conservatives and Reformists Group — define themselves in terms of economic liberalism. They suffered a loss of 11 seats. In contrast, the United Left parties — often called the far left — gained ten seats to 45 and the Europe of Freedom and Democracy — often called the far right — put on 11 seats to 40. There was no victory of right over left, only of Eurosceptic parties over pro-European parties, of interventionists over free marketeers. If you were to rationalise the party groupings in Strasbourg you would bring ‘far left’ and ‘far right’ together under a new umbrella grouping of xenophobic statism.

The further Europe heads in this direction, the greater will grow the economic gap between Europe and the US. While America has its protectionist lobbies, and a racist, xeno-phobic fringe, there is a growing philosophical gulf between big-government Europe and small-government US. It is reflected in a growing economic gap between a sclerotic Europe and a rebounding America. With sclerosis comes political extremism. A generation ago, you had to look to America for the likes of the Ku Klux Klan, while Europe seemed a model of moderate social democracy. But it is not America which is producing groups such as Jobbik and Golden Dawn.

An overlooked aspect of the election is that Britain rejected this agenda. The British National Party was buried, losing its European parliament seats and 80 per cent of its voters. Its racism was never widely shared; it prospered as a protest party. Now the explicitly anti-racist Ukip has given a voice of protest far truer to British instincts: chiefly, the desire to be left alone by meddling bureaucrats. Nigel Farage has killed Britain’s only neo-fascist party and deserves warm congratulations. Britain’s voice of protest says it welcomes immigrants of any creed and colour.

The tragedy of the EU is that it stands for so many of the right things. At its best, it negotiates free trade deals and tramples down barriers to mobility of labour. But this process has been corrupted by special interest groups which tweak trade rules to their advantage. It speaks volumes about the European parliament that we have just had an election in which policy hardly featured at all.

We had plenty of insults flying in all directions. But we learned hardly anything about the issues on which the representatives will be voting. If the policies of the ‘far left’ and ‘far right’ parties which won were subjected to proper examination, we would be able to see how similar they really are. And how little British politics has in common with either.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in