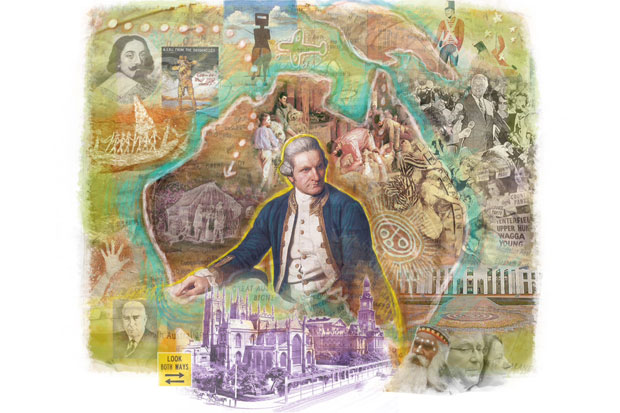

This is a bold attempt to write the history of Australia in 1,200 pages of narrative. A huge team of almost 70 authors come forward, mostly armed with fresh research and insights, but sometimes with much indignation. The work, beginning with a short survey of indigenous history before 1788, discusses the arrival of the first Aborigines from Timor or the Indonesian archipelago, though where they landed remains a topic of perpetual debate. In my view it is almost time for Canberra to erect a monument to these forgotten discoverers.

As the Aborigines multiplied, about 60 species of native fauna died out. In this extinction the Aborigines possibly played some part. Later the rising of the seas and the separating of New Guinea from Australia largely isolated the Aborigines. Even so, the dingo eventually arrived in the company of later immigrants who possibly had genetic links with India: the book does not discuss such links.

Written by two leading archaeologists, Peter Veth and Sue O’Connor, this impressive chapter sees Aboriginal culture as adaptable and dynamic. It leaves vital Aboriginal themes for other authors to take up or develop, but most of these themes are somehow dropped or skimped

As readers press on, they will find only token mention of what I think is the most influential event in Australia’s human history: the rising of the seas and a period of global warming which makes anything predicted for the next 200 years seem trivial. In this chaotic era the Aborigines somehow coped: to cope was a triumph.

My feeling is that the book short-changes Aboriginal history while pleading its importance. Thus in the book’s chronology of several hundred important events, a mere four events happen before the time of the Dutch explorers. Four notable events in some 50,000 years mistakenly suggest a land with no news.

The last big-scale history of Australia was published a quarter century ago, and its opening volume gave long coverage to most of those Aboriginal topics neglected here. On the other hand this book is more authoritative on events since 1788. At least a dozen chapters are written with flair and a telling eye for detail. By current international standards that is a good success rate for a multi-authored work.

New light is thrown on the convicts (this book tends to disagrees with Robert Hughes and his brilliant but gloomy Fatal Shore), on the treatment of Aborigines in early Sydney and elsewhere, on the 1850s goldfields, on the role of education, science and technology and on the Federation Drought when three El Niños arrived in a row. The whole book reveals more about Sunday than Saturday, the spectator sports taking up few pages compared to Christianity.

We are escorted into the first Commonwealth parliament in 1901. I had forgotten how strong the free trade movement was, even among Labor politicians. Not until 1908 did Australia lay the deep foundations of that Great Wall of Protection, now toppling before Toyota’s and Ardmona’s eyes.

It was the first parliament which entrenched the White Australia policy and resolved to deport most of the Pacific Islanders working on sugar-cane farms. Queensland was emphatic in supporting this decision. ‘It was as if the American South in 1860 had voted for Abraham Lincoln’, explains John Hirst in an illuminating sentence.

The first world war and its peace treaty are narrated in an arresting way. While some historians now claim that Sir John Monash was the Allied general who won the war on the western front, the authors’ verdict is cautious: ‘he was a highly competent commander.’ The world depression, second world war and latterday economy are explained, and we watch the campaigns for Aboriginal, female and environmental rights take off in the 1960s and hear the occasional stamping of feet on the soap box. The quiet conquest by television is rightly called the ‘most significant cultural change in the postwar decades’.

Robert Menzies, prime minister in 1939-41 and 1949-66, is depicted as often against change, but maybe he was really against fast change. It was in his last year that the unimaginable happened, and East Asia passed Britain as Australia’s main export market. As Judith Brett briefly explains. the Country (National) party under John McEwen promoted — with Menzies’s blessing — the economic swing towards Asia while Labor initially opposed it. The fast road to Asia had detours. A few years later, Lonely Planet issued its first guide to Asia and assigned more column inches to finding dope than accommodation.

On Whitlam and his brief era, Paul Strangio concludes that his government — ‘composed mostly of ageing political veterans with long-harboured ambitions’ — coined slogans for tomorrow while locked into yesterday, financially. Even Rudd and Gillard are X-rayed. My impression, after reading these two volumes, is that in the last 60 years the typical university historians have become more skilled than their predecessors in intellectual concepts, but rather less at ease with geography and mental arithmetic.

The book ends with a grievance: ‘From the mid-1990s until Howard’s departure as prime minister in 2007, “history wars” dominated the nation’s media. Raging across a wide cultural and political front, led by conservative politicians, journalists and intellectuals, and fuelled by the vigorous support of Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, they were marked by intense and often acrimonious public debate regarding the history of indigenous-settler relations.’ This verdict, by Mark McKenna, somehow forgets the Asian financial meltdown, the bombing of the twin towers, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and 20 other events that towered over the history wars.

There can be no history without debate and no history without historians. But as historians we come and go, in the twinkling of an eye, while momentous events like the Great Rising of the Seas exert their sway for thousands of years.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Professor Geoffrey Blainey has written more than 30 books including a history of indigenous Australia in 1975 and a history of Australia in 1994

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.