It was only with ‘continuing misgivings’ that that self-proclaimed radical Tory, Garfield Barwick QC, agreed in 1953 to accept the honour of knighthood. And so it is only the most radical Tory who would rush in, over 60 years later, to reinstitute the honour, 30 years after its seeming abolition. Fools rush in where angels fear to tread, and over the past week there has been no shortage of angels singing the foolishness of Tony Abbott.

When Gough Whitlam established the Order of Australia in 1975 there was no provision for the class of knight and dame (AK and AD). In 1976 Malcolm Fraser advised the Queen to amend the Letters Patent in order to create a new and more senior class of AK and AD within the Order. In 1986 Bob Hawke advised the Queen to amend the Order once again to remove the new class. Paul Keating was content with this, and focused his attention on trying to remove the Queen from being Sovereign of the Order by reconstituting Australia as a republic. Although Australians voted against becoming a republic in 1999, staunch monarchist John Howard resisted calls for the AK and AD to be reinstated. The following two republican prime ministers were content to leave the Order alone, and no one would have envisaged any radical changes to the Order (unless Australia were to become a republic) until the surprise announcement last week that the Prime Minister had advised the Queen to reintroduce knighthoods.

Read in this light, the decision is part of a long squabble between the ALP and the Coalition over the appropriateness of knighthoods in Australia, a squabble that the ALP might have been interpreted to have won, when Howard conceded that the days of Australian knights had passed.

John Howard has said that he finds the restoration of the AK and AD ‘anachronistic’. He writes in his memoirs that he considered this possibility himself, but decided against it. So it is hardly surprising that he is not keen on it now. However, it has to be remembered that Howard belongs to an era when the status of the monarchy in Australia was highly contentious, and any move to restore an institution linked to the monarchy was highly controversial. But times change: on 2 February 2014 the Sydney Morning Herald announced that ‘Voters’ support for republic hits 20-year low’.

Perhaps it is because the public is no longer actively hostile towards the monarchy, in the way it was fleetingly in the 1990s, that the critical response from the political class, the fourth estate and the intelligentsia has taken the form of ridicule rather than condemnation, as it would have in Howard’s day. If this is a ridiculous idiosyncrasy of the current Australian prime minister, it is one that he shares with his New Zealand counterpart. When John Key restored knighthoods in New Zealand in 2009, he gave the existing Principal and Distinguished Companions of the New Zealand Order of Merit the option of using the title Sir/Dame, and 72 of the 85 Companions jumped at the opportunity. (Of course, New Zealand has always been rather anachronistic: they even embraced gay marriage.)

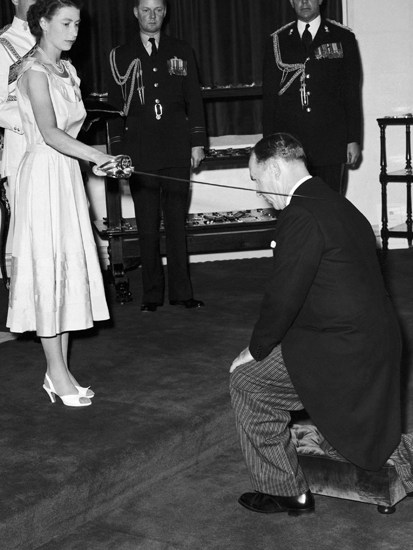

Announcing the reintroduction of knighthoods and dameships, Abbott emphasised that the AK and AD will be awarded sparingly, and only for the purpose of honouring those who have given service of the most exceptional nature to the nation. Even cricketers will not be eligible.

Insofar as this move is intended to recognise pre-eminent service to the nation, it is surely not contentious. Australians feel comfortable recognising all forms of eminent service through the award of AC and, arguably, recognising pre-eminent achievement in some particular field through the award of Australian of the Year. So it can hardly be that recognising pre-eminent service to the nation is worthy of criticism, let alone derision. What has prompted this response is the means by which the Prime Minister believes we should recognise pre-eminent service to the nation, namely conferring knighthoods and dameships.

The move has been criticised as a return to ‘Imperial honours’. It’s a small point, but an AK or an AD is not an ‘Imperial honour’. After the Order of Australia was created in 1975, state and Commonwealth governments were still entitled to make recommendations to the Queen to appoint Australians to the Imperial orders (for example, the Order of the British Empire).

The real issue is not that knighthoods and dameships are ‘imperial’, but that they are reminiscent of hereditary titles. Hereditary titles did much to legitimise the hereditary political power of the English ruling class.

Knighthood is an expression of chivalry. It does not denote hereditary precedence or power. Historically, knighthood was conferred on the battlefield. It reflected ability to fight, in particular horsemanship as exemplified in the joust, and the service rendered in battle. So at its core, it is a title that was conferred in order to recognise a particular kind of achievement and a certain form of service. It developed into a code of conduct which commended bravery and courtesy and was a forerunner of the notion of professional ethics. It has a long, rich and romantic history centred on various forms of chivalric service and duty demonstrated by knights. It is a history that also became famously corrupt, when it became fashionable for monarchs and governments to sell honours.

We use titles to recognise a variety of different forms of public service, academic attainment and professional standing. Is it really so offensive to reserve a single syllable for recognition of pre-eminent service to the nation? Reflecting on the success of Dame Quentin’s term of office, Abbott noted, ‘But that’s what Governors-General do — they encourage us to be our best selves. They are our cheerleaders-in-chief. They celebrate all that is good in our community in the hope that we just might live up to it… Happily, it’s easy to be proud of Governors-General providing leadership beyond politics and appealing to the things that unite us.’ It is fitting that we select someone pre-eminent to celebrate our achievements and to provide such leadership. And in doing so, surely we ought to be willing to pay respect to the pre-eminence of the person who is deemed worthy of celebrating our achievements.

‘Governors-General, like the monarch they represent, are the dignified part of our Constitution,’ Abbott said at the reception following Sir Peter’s swearing in. But there is a sense in which dignity sits uncomfortably with the Australian attitude to life. In an egalitarian world in which people like to address one another by their first names, it feels like one is back in the schoolroom if one is to say ‘Ms Bryce’, even when one knows it would be unacceptably informal to address the Governor-General as ‘Quentin’. Here, we find that the language of chivalry offers us the perfect solution: ‘Dame Quentin’—a compromise between the informality of her first name and the dignity of a title.

However, even such a compromise between informality and dignity is offensive to some. The political class has replaced the ruling class, and it is hardly surprising that the Australian political class has spurned hereditary titles which are the symbol of the class that it has replaced. Its scorn for the AK and AD is shared by the fourth estate and the intelligentsia in Australia. I can’t help feeling that a big part of the reason that they have heaped ridicule on the reintroduction of knighthoods is that there is no place for the values associated with chivalry in the contemporary Australian political class, fourth estate or intelligentsia.

In his attitude to the value of chivalry, Tony Abbott finds himself as much at odds with the values of the political class, the fourth estate and the intelligentsia in Australia as he does on the value of religion, the symbolism of the monarchy and the nature of marriage. Because he does not share their views, they accuse him of living in the past.

His commitment to showing respect for those who have given pre-eminent service to the nation has invited accusations of pomposity and pretentiousness. But there is a fundamental error here: to recognise the pre-eminent service of others is to demonstrate personal humility. Far from being aloof from ordinary people, this week we learnt that he has ‘reluctantly’ moved his family out of their humble family home and into the considerable more grandiose Kirribilli House for security reasons.

In The Minimal Monarchy, Abbott writes of his family home in Forrestville:

The street I live in is called Lady Davidson Circuit—because it runs along the edge of a large bushland park originally named after the wife of an imperial dignitary. A few years ago, the park was incorporated into a larger area with an Aboriginal name but the street name stayed the same. This is a homely example of cultural evolution writ small. As Australia’s independent history lengthens, what is ‘British’ diminishes and what is ‘Australian’ increases. Yet over time, what was once ‘British’ becomes incorporated into what is now Australian.

When it comes to knighthoods and dameships, the real issue is whether the values associated with chivalry can be incorporated into what is now Australian, or whether they are fundamentally incompatible. A certain attitude to aristocracy was part of our British inheritance. The values associated with the ruling class are clearly unacceptable in Australia today, and cannot be incorporated into what is now Australian. But I, for one, should like to think that the values associated with chivalry are compatible with Australia today, and that we can incorporate an expression of our admiration for pre-eminent service to the nation into the language we use in what is now Australian public life.

Addressing Quentin Bryce as ‘Dame Quentin’ rather than as ‘Ms Bryce’ is about showing respect. It is not about showing respect for her as someone who is better than the rest of us. It is about showing respect for her as someone who exemplifies pre-eminent service to the nation. Ultimately, it is about acknowledging that how we address those who exemplify pre-eminent service to the nation is an expression of how we feel about pre-eminent service to the nation.

Chivalry affords us a natural way of giving expression to our respect for those who have given exemplary service. There is a range of different things that we ought to respect, but our society has fallen out of love with the concept of respect. We would do well to reinstate language that gives expression to respect for those things that are worthy of respect, one of which is undoubtedly pre-eminent service to the nation.

Perhaps titles bring out the foolishness in all of us — even the man credited with giving Australia its ‘egalitarian’ Order seems to have been susceptible. Although Gough Whitlam did not make provision for knighthoods and dameships, he was responsible for Australia’s most famous Dame: during his unscripted cameo in a scene shot at Sydney Airport for Barry Humphries’s film Barry McKenzie Holds His Own, Whitlam welcomed Mrs Everage back to Australia by proclaiming her ‘Dame Edna’.

In the end, even that archangel couldn’t help rushing in where angels fear to tread.

Damien Freeman’s forthcoming books include an edited collection, Figuring Out Figurative Art: Contemporary Philosophers on Contemporary Paintings (Acumen, 2014) and a family memoir, The Aunt’s Mirrors (Brandl & Schlesinger, 2014).

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Damien Freeman’s forthcoming books include an edited collection, Figuring Out Figurative Art: Contemporary Philosophers on Contemporary Paintings (Acumen, 2014) and a family memoir, The Aunt’s Mirrors (Brandl & Schlesinger, 2014).

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.