Here we go again. The Royal Commission into trade union ‘slush funds’, commencing 9 April, will be the sixth into trade unions. The first three investigated wharf and maritime unions, the last two, building unions. The earlier union inquiries essentially concerned misbehaviour in the marketplace. The slush fund inquiry concerns alleged corruption among officials. The difference is significant. Trade unions are no longer in the vanguard of political ideology or raw industrial power. The inquiry is solely into improper means of holding power within the labour movement, albeit with the help of compliant firms.

The links between the union movement and the ALP have been enduring. Affiliated unions fund the party and, in return, union officials trade in preferred candidates for parliament. This despite the fact that since 1984 all political parties have received public funding for elections.

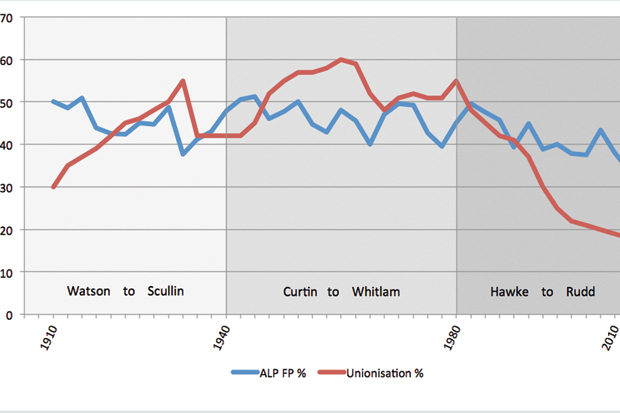

Party-union relationships span three ages. Labour’s first age witnessed a startling leap into the political arena, with Federal Labor capturing 50 per cent of the first preference vote at only its third outing. A parallel jump took place in union coverage in the workforce, reaching 55 per cent before falling under the weight of the 1929 crash. Chris Watson, Australia’s first Labor prime minister in 1904, later worked as an organiser for the Australian Workers Union in New South Wales.

Significant political moments were the turnabout governments Andrew Fisher led, the struggle over conscription for the first world war and the role of Billie Hughes in it, and the fiscal response to the 1929 crash that helped to bring down the Scullin government.

The second age opened with the election of John Curtin, a former Victorian Timber Workers Union and AWU official, as prime minister in 1941. Growth in the number of trade union members peaked at 60 per cent per cent in 1961. Trade union membership began to decline to 50 per cent by the early 1970s, but not in strength so much as as a percentage of the workforce, with women entering the expanding services sector.

Significant political moments were the Chifley government and Chifley’s signature ‘Light on the Hill’ speech, which has become a touchstone for subsequent Labor prime ministers. The struggle to weed out Communists from the trade union movement, in part the cause of the split with Catholic labour, were important years for Australia. The cost to the ALP was an electorally barren 23 years. The election of the Whitlam government revived hopes of political maturity and an electoral acceptance.

These were not fully realised until the third age. The election of Bob Hawke in 1983 signalled a distinctive ideological change. Hawke was president of the ACTU prior to entering parliament and the ACTU played a crucial role in the Hawke and Keating governments. The trade union movement assisted Labor to transfer economic power to the market. Arguably, the third age was the most successful, the ALP spending its greatest proportion of time in government. But it was a turning-point in the ALP union relationship. Privatisations, changing workplace relations, increase in part-time and casual employment and changing industry composition contributed to a decline in trade union coverage more rapid than the increase witnessed in 1910-1927.

Former AWU national secretary and opposition leader Bill Shorten has inherited, courtesy of the Rudd-Gillard governments, a vote of 33.8 per cent at the 2013 election, the lowest since 1903. At the same time, trade union membership is 18 per cent of the workforce and 13 per cent of private sector workforce. A fraction of the union movement is affiliated to the ALP.

When the next Labor leader contests a winnable election, in 2019, it will be 36 years since Bob Hawke was elected. Much will have changed. Industry is no longer protected. Labor’s ideology remains egalitarian and heavily intellectually indebted to the grievance industry and identity politics — and public sector jobs. Labor’s major enduring threat comes from the environmental movement.

Organised labour has migrated to the education and training industry, which has the highest proportion of trade union membership at 38 per cent, and public administration and safety at 34 per cent. Unions in these fields broadly are not affiliated to the ALP, but with party membership so low, union leaders are arguably more in control of the ALP than has been the case for decades. Labour’s base is no longer rusted on. Then again, neither is the Liberal party’s. Liberal success has almost always relied on coalition with the Country, now National party, whose ideology it barely shares.

A new Labor leader will emerge. Paul Howes, recently resigned as secretary of the AWU, has jumped ship. The ALP had better hope that he jumps to the parliamentary side. It is doubtful that a fourth age of labour will emerge with the ALP trade union nexus intact. By the time the Royal Commission completes its task, trade unions will look shop-soiled. Having marched so long beside a trade union banner — indeed, having offices in each state often adjoining the trades and labour councils — the ALP will march to a different tune.

The question is, which tune? Without unionists, the party is likely to fall to inner-city leftists with a consequent shift towards the Greens’ ideology. Should this occur, the ALP would become a minority party, governing in conjunction with the Greens. Recent examples, federally and in Tasmania, are not reasons to shun future deals. To avoid inner-city capture and permanent minority status, the ALP must move to a primary system for the selection of candidates. And it must reverse the rule that allows members to choose the leader. The leader needs flexibility to govern. As long as voters are given the choice of a Blue team and a Red team, Australia should be able to maintain stable government. If not, Clive Palmer populists wait. The future of the Red team lies in trade union leaders letting go.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Gary Johns, a federal Labor MP from 1987 to 1996, was a minister in the Keating government.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.