W.H.Auden once wrote: ‘Real artists are not nice people. All their best feelings go into their work and life has the residue’ — which puts those who aspire to be artists in a bit of a quandary. Is it a measure of one’s success as a ‘real artist’ that one is not a nice person? Is it in fact possible to be a real artist and a nice person? And, if it is not, is it better to be a real artist or a nice person? Auden, who was speaking from first-hand experience, implies that it must be one or the other.

By the time he wrote this, Auden was sure of his standing both as an artist and as a person. His friends might say that he was a nicer person than he thought he was, but no one was going to say he was not a great artist. The quandary is for those who are not quite sure of their standing as artists, and who are tempted to think that bad behaviour proves that their creative work must have a certain worth. And that, by extension, the public will forgive them their bad behaviour out of respect for their work.

The most impressive cases are those where centuries after the event we admire the work and find the life entirely forgiveable. If Caravaggio had to live in such a rough milieu that he murdered his friends, we wouldn’t want his paintings to be any different — and perhaps if he had stayed his hand his paintings would be less adventurous. Presumably Christopher Marlowe didn’t get stabbed in the eye because he was in the wrong place at the wrong time, but because he lived that sort of life. Even that arch-shit Richard Wagner, despite being a sponger and adulterer, is let off the hook for being a tedious human being because he created towering masterpieces that we love. So far, Auden was right.

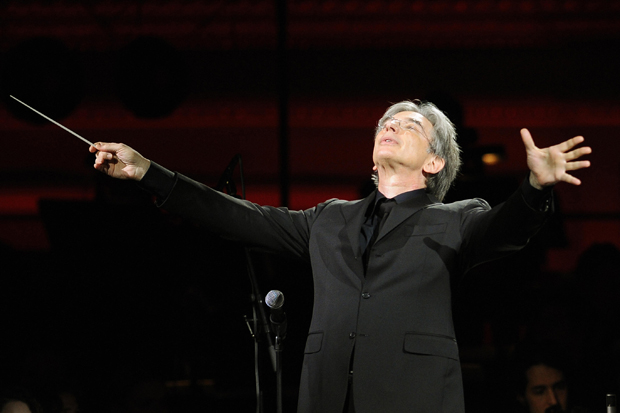

The problem is with musicians, and in particular with performing musicians, whose reputations can never be as secure as those of composers: the former are recreative artists, the latter creative, with posterity always remembering the creative ones, no matter how good the former may have been in their lifetimes. When one hears of outrageous behaviour among practising musicians, the first thought is that they think their greatness will protect them from opprobrium. This is despite the fact that every musician knows they will perform better if they are encouraged rather than being shouted at. In this day and age, to have to play or sing in a state of fear of the maestro out front is simply counterproductive. No one will tolerate it; nor should they.

I wonder to what extent Auden’s remark may be applied to the story that John Eliot Gardiner recently lost his temper with a brass player in the London Symphony Orchestra. His ‘notorious rudeness to performers and colleagues’ has been referred to in these pages by Stephen Walsh. What do we think of that? Do we love his music-making so much that we forgive him the odd peccadillo? Perhaps we think his music-making must be all the better for it. What is certain is that Gardiner is no Wagner: his achievements are likely to be forgotten soon after his death, as is the case with just about every conductor there ever was. If this is true, do we still indulge him?

This kind of behaviour derives from a whole host of out-of-date impulses: the maestro’s belief that he is right by definition; that women are less strong contributors than men, whose talents should not be taken on an equal footing (I think of the Vienna Philharmonic here); that any form of recording, video or audio, is a higher form of activity than mere concert-giving, deserving of extra respect, preparation and financing (I think of the Tallis Scholars here).

I find I have a visceral reaction to any evidence that a conductor feels he is so above his colleagues that he can lord it over them and abuse them. Any music worth performing has to be a collaborative venture. Rank and file players and singers these days have already spent many hours being lectured to, on the way to becoming qualified — they do not need any more of it from the podium. They need to be encouraged. Recreators of other people’s ideas should remember that they are not unique — there is always another way of looking at a masterpiece — and that anyway in another 20 years or so there will be a completely new wave of performers who will be all the rage, for a while. Even Abbado’s work may not be much remembered in a few years’ time.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in