As I looked out of the window of my hotel bedroom, studying the view of central Damascus, the mobile phone rang. Peter Walwyn was on the line. I have not seen Mr Walwyn, who was twice British champion racehorse trainer and trained Grundy to win the Derby in 1975, for several years. I reminded him of our lunch at Simpson’s-in-the-Strand. He had sat down, ordered a vodka and tonic, and told me that the evening before he had placed flowers on Jeffrey Bernard’s grave. After Bernard died several Lambourn trainers, along with Peter O’Toole, held a ceremony at the top of the gallops. A simple granite stone memorial now marks the spot. I think that the Low Life correspondent of this magazine would have felt great happiness and pride that the daffodils swaying in the breeze beside the huge beech tree at the top of Faringdon Road gallops in Lambourn this spring were planted in his memory by one of the finest and most popular racing trainers of the 20th century. At the very least he would have fallen off his bar stool.

Peter Walwyn’s wife of 60 years, Bonk, died in January, and a quotation from Bernard was on her funeral service sheet. It read: ‘The following morning we went to Lambourn to see Peter and Bonk Walwyn. Bonk pulled my shoes off and left a large vodka, ice and soda on the bedside table. You can’t ask for more even from your own wife.’

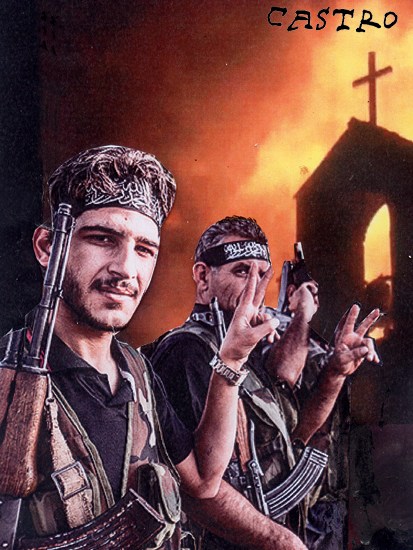

I was still feeling exhilarated by my conversation with Peter when I travelled across town to Bab Touma (St Thomas’s Gate) in Old Damascus to interview Armash Nalbandian, the Armenian bishop. He said that 11 of the 32 Armenian churches in Syria have been bombed or attacked during the conflict. He was incensed by recent events at Kasab, an Armenian village close to the Turkish border in northern Syria. He told me how villagers had been attacked in the early hours of the morning by militant groups. ‘These groups were supported by the Turkish army. Our people there, they witnessed that.’ Almost the entire population of Kasab has fled, while the al-Qa’eda aligned group al-Nusra is said to be patrolling the streets.

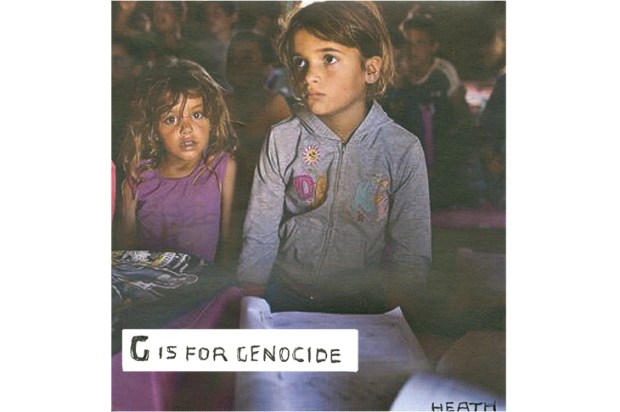

Next year marks the 100th anniversary of the Armenian genocide, a tragedy which Turkey to this day refuses to acknowledge. The bishop was careful to stress that no one was killed during the attack on Kasab. ‘Please don’t compare this to the Armenian genocide. Nevertheless the only thing that I can say is that the Turks are the ones who committed that genocide and are now behaving the way they are in Syria.’ Nora Arissian, a Damascus-based historian of Armenia, told me: ‘It was not genocide, but it was a forced evacuation and ethnic cleansing because many inhabitants have had their homes looted and stolen.’

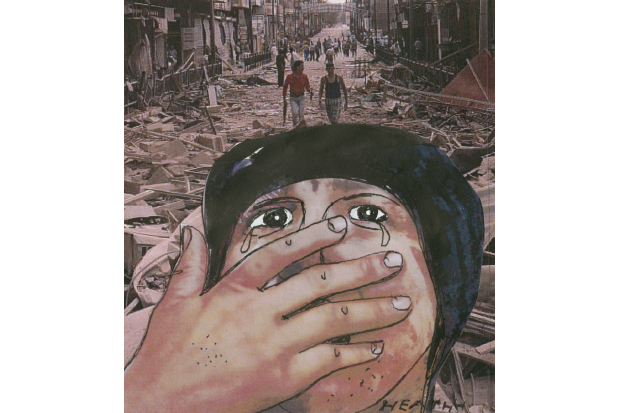

It is a short 200-yard journey up Straight Street (along which St Paul walked in the Bible) from the Armenian church to Al-Zaytoun Greek Catholic church. There I attended a crowded service of incomparable peace and beauty. Six mortars fell nearby as we prayed, and the church precincts had been struck twice by mortars in the last week. Later I had dinner with a dentist who told me of his despair that the West showed no concern at the plight of the Christian community in Syria. He offered his own explanation: ‘To the jihadists we are kafirs. But to the West we are just Arabs.’

David Cameron last week declared that Christians ‘are now the most persecuted religion around the world’ and committed his government to fighting this persecution: ‘We should stand up against persecution of Christians wherever and whenever we can.’ There is no doubting the Prime Minister’s sincerity. However he needs in all truth to acknowledge that his own policies, like those of Tony Blair before him, have contributed to the isolation and terrorisation of some of the most ancient Christian communities in the world. There are thought to have been 1.5 million Christians in Iraq before the 2003 invasion. Ten years later over one million have fled. More than 300,000 Iraqi Christians went to Syria, which is no longer (partly thanks to British policy) a safe haven. For all Bashir Assad’s faults, during his regime he was careful to tolerate many of the minorities (so long as they acquiesced in his regime) — communities that had lived in Syria securely for thousands of years and make up some of the most ancient civilisations in the world.

In spite of the real dangers to minorities in Iraq and now Syria, Britain and the United States have so far accepted only a handful as refugees. If David Cameron’s pledge to Christians around the world is to have any meaning, perhaps he should not offer them the safe haven that is being destroyed in Syria.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in