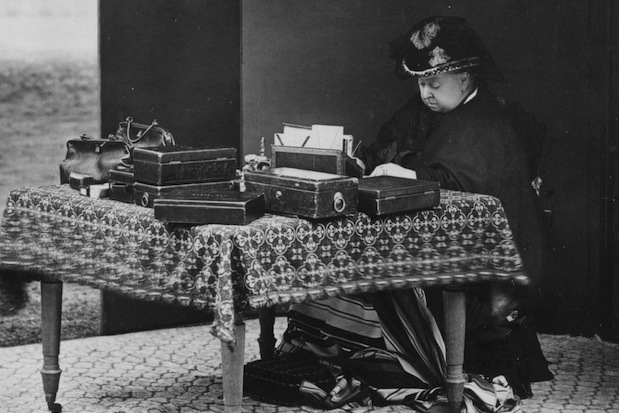

The genesis of The Road to Middlemarch was a fine article in the New Yorker about Rebecca Mead’s unsuccessful search for the origin of the remark, sometimes attributed to George Eliot, that ‘it’s never too late to become the person you might have been’. To Mead this seemed at variance with the concentration in Middlemarch on ‘the melancholy acknowledgment of limitation’.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £13.99, Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in