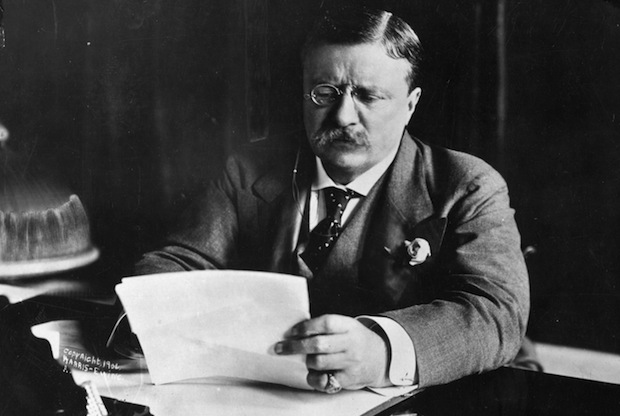

Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Era are well-worn subjects for both professional and amateur historians, so it’s pertinent to ask why Doris Kearns Goodwin devoted so many words —and her considerable reputation — to the writing of The Bully Pulpit. Kearns’s thesis seems clear enough: at the close of the 19th century, mythically egalitarian America was in reality teetering on the brink of genuine class warfare. Something urgently needed to be done to prevent an explosion between a furious, increasingly violent labour movement and a cohort of arrogant monopoly capitalists, whose collusion with corrupt politicians had made them virtually invulnerable. Economic strife had stretched the social fabric to breaking point. The country required heroes and visionaries to save the day.

Into the breach leapt two men of extraordinary intelligence, ambition and neurotic energy: the patrician-turned-politician ‘Teddy’ Roosevelt, and the Irish poor boy Samuel McClure, whose ‘muckraking’ magazine dominated political discussion during Roosevelt’s heyday. As Kearns writes, they bore ‘an uncanny resemblance’, despite their very different origins:

While Roosevelt’s tumultuous energy elicited comparison to that force and marvel of nature Niagara Falls, McClure, ever threatening to erupt in ‘a stream of words’, was likened to a volcano.

On the most obvious level their common cause was political reform — regulating the railways and the industrial trusts, defending the rights of labour unions, popular election of US senators and breaking the power of state and municipal political machines — but the real engine that drove them was a craving for renown.

Brought up until the age of nine in Co. Antrim, McClure was the more classically self-made American. But privileged, Harvard-educated Teddy was no less a self-invention: rejecting a life of ease, he was by turns a cattle rancher, big-game hunter, naturalist, prolific writer and, in his most theatrical incarnation, a self-appointed soldier and imperialist, extending the white man’s burden to Cuba and the Philippines. This would have been enough for most men, but Teddy burned to become president.

As governor of New York, Roosevelt, though far from a revolutionary, was viewed as a boat-rocker by his social class and the Republican Party establishment that tried to keep him under control. Thomas Platt, the New York State boss, wanted the popular reformer out of the way, so he manoeuvered the reluctant Teddy into becoming William McKinley’s running mate in 1900. Thus Roosevelt entered the White House by fortuitous accident rather than by tactical design. ‘Utterly frustrated and dispirited’ as vice president, according to Goodwin, he was considering a return to law school when President McKinley was assassinated on 6 September 1901. Openly delighted by this unexpected opportunity, Teddy, at 42, became the youngest president in American history, and the most aggressively active since Lincoln.

By the end of his first term, he had brought an anti-trust suit against the giant rail and shipping conglomerate Northern Securities Company, intervened personally to settle the Pennsylvania coal strike, secured the passage of bills creating the Department of Commerce and Labor and strengthened the regulation of the railways. During his second term, he went further, pushing through legislation that granted the Interstate Commerce Commission explicit power to set freight rates (until then manipulated by the railways in favour of the coal, oil, steel and beef trusts), instituted comprehensive slaughter and meatpacking inspection, and brought about the Pure Food and Drug Act.

In all these efforts, the President was supported by the big three investigative reporters of McClure’s Magazine: Ida Tarbell, Ray Stannard Baker and Lincoln Steffens. The sensational details exposed by these journalists made palpable the plutocratic power of big business, most famously Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, but also exposed machine politicians and corrupt labour bosses. According to Goodwin, it was a ‘golden age’ for civic-minded journalism, although what she seems to admire was the unparalleled collaboration between three brilliant reporters, their publisher and the President of the United States.

Was Roosevelt using McClure’s or was McClure’s using Roosevelt? The ethics don’t much matter to Goodwin. Teddy had early on recognised the value of good publicity and friendly relations with reporters to advance his career and agenda, while Sam McClure was happy to ride the public’s outraged mood, and TR’s coat-tails, to gain a larger circulation. But in the end, Roosevelt was not bold enough for McClure’s. As the big three moved farther left, Roosevelt decided that the investigative vogue had gone far enough, and in 1906 he denounced ‘muckrakers’ who, he said, produced ‘sensational articles’ without acknowledging ‘the good in the world’.

Ray Baker was equally disdainful: ‘Roosevelt never leads; he always follows. He acts, but he only acts when he thinks the crowd is behind him.’ Teddy considered the reporters politically naive. In a letter to Steffens, he praised ‘men who take the next step; not those who theorise about the 200th step’.

Significantly, the magazine published by the highly-strung, depressive McClure began to come apart at the seams at about the same time as the influence of its star writers began to wane with Roosevelt. McClure’s psychological collapse presaged Teddy’s own political nervous breakdown when, in 1912, he unsuccessfully challenged the bland but honest Republican incumbent, William Howard Taft, his hand-picked successor and former friend, in the Republican primaries. His ‘Bull Moose’ third-party bid was hopeless, and the splitting of the Republican vote paved the way for the election of the Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

Goodwin presents Roosevelt as an almost entirely admirable liberal, barely mentioning the brutality of America’s counter-insurgency in the Philippines, and for the most part skipping over the larger implications of the nascent American empire. She fails to quote Teddy’s most racist and jingoistic writing. But worse than her omissions is her timid prose — her apparent refusal to analyse anything on her own, preferring to rely on the opinion of other historians or the direct quotation of the major players (she may still be smarting from plagiarism charges concerning an earlier book). Her narrative is only as interesting as the hundreds of quotes she strings together. Too often they are dull.

So, with no breaking of new ground, what’s the purpose of this book? Goodwin never states it, but I discern a misplaced nostalgia, not so much for Theodore Roosevelt or good journalism but for the ‘Camelot’ of John F. Kennedy. Goodwin’s husband, Richard, was a Kennedy family courtier, and clearly she is attracted to Roosevelt’s ‘style’ and to the cult of the JFK-like virility and glamour that surrounded him. The cooperation between Roosevelt and the muckrakers bears some resemblance to the intimacy between Kennedy and his court scribes, including Arthur Schlesinger and Ben Bradlee. ‘Smart society clamoured for invitations’ to the Roosevelt White House of Teddy and Edith, as it would 50 years later to attend the court of Jack and Jackie. For Goodwin, I suspect, it’s not a coincidence that Pablo Casals performed twice at the White House, in 1904 and 1961.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £15.95. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in