‘You have no idea,’ wrote the publisher Ralph Hodder-Williams in 1929 to one of his authors,

what terrible offence Journey’s End has given — and terrible pain too, which is a great deal more important. I think you will agree that the chronic alcoholic was extraordinarily rare.

He was referring to R.C. Sherriff’s controversial tragedy of the trenches, which was then, 11 years after the war, enjoying an unexpected box-office success in the West End, where it played for nearly 600 performances.

Its success came as a surprise, not only because Sherriff (1896–1975) was an unknown writer, and exclusively male war plays were not particularly popular, but also because audiences were expected to sympathise with an unusual war hero. Stanhope is a young company commander, whose nerves by the time of the action are so shattered that he can only keep going with liberal doses of whisky. Hodder-Williams (a war veteran himself) was among those who dismissed this as sensational.

Army authorities, too, objected: they claimed that the play had seriously affected peacetime recruiting figures, contributing to a growing climate of disenchantment with military life. Its appearance, in the late 1920s, coincided with two of the greatest successes of first-world-war literature, All Quiet on the Western Front and Goodbye to All That. The message of these was that the war had been pointless, a colossal waste of young lives and built on deception. For many, Journey’s End seemed to say the same thing, with the tragic death of Lieutenant Osborne, a father figure to the youths surrounding him; with Stanhope’s alcoholism; and with the pathetic end of the boy-officer Raleigh, who had arrived at the Front with childish expectations of military glory.

Like much war literature in Britain that came after the Great War, however, the play’s attitude to the conflict was ambiguous. In fact it exalted what were conventionally characterised as the ‘military virtues’ of courage and ‘sticking it’; above all, Sherriff valued the companionship of the trenches, and for years afterwards attended his regiment’s reunions.

Journey’s End was anathema to Joan Littlewood, who, as producer of the satirical 1960s musical Oh,What a Lovely War!, set the tone for rubbishing the residual ‘valiant hearts’ patriotic sentiment about the Great War. In Littlewood’s view, Journey’s End not only glorified public-school values and poked fun at its working-class characters, such as the food-obsessed Lieutenant Trotter, but never questioned the war’s purposes.

What is the secret of the play’s success? Above all, though a writer of no intellectual pretensions or particular distinction, Sherriff was absolutely sincere, and the play reflected his experience, revisited to get it out of his system, as with many, such as Robert Graves, Siegfried Sassoon and Edmund Blunden. Unlike those writers he had no gift of poetic expression, but he conveyed how ordinary people talked and thought; and he had a turn for drama. Nothing he wrote subsequently had the power of Journey’s End, but — for example in The Long Sunset, his play about the last days of Roman civilisation in England — his build-up of suspense, as order and humanity break down, is chilling.

Educated at Kingston-on-Thames Grammar School, Sherriff was an insurance clerk when war broke out. He volunteered for the army, and in 1916 was commissioned in the 9th East Surrey Regiment. He saw active service over ten months until pulled out of the line wounded during the dreadful third battle of Ypres when a shell hit a nearby pillbox (the medics extracted over 50 pieces of concrete from his face and body).

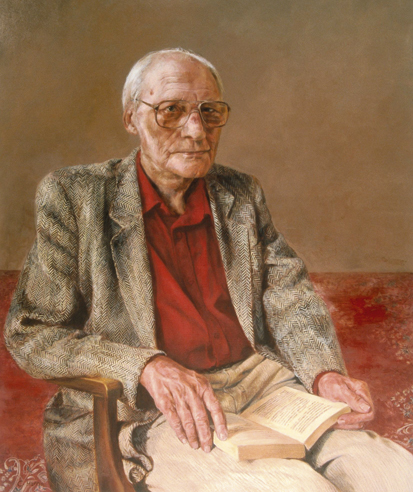

As a soldier, Sherriff seems to have been responsible and competent and as nervous of failing in his duty as of enemy shells; he was obsessed for months with containing fear, which was to be one of the principal themes of Journey’s End. A photograph taken of him in 1916 is revealing of his character — gentle, straightforward, sensitive, guarded. What it does not show is his sense of humour, evident not so much in Journey’s End as in other works such as the novel A Fortnight in September. Journey’s End made him rich, and his career as a novelist, playwright and scriptwriter prospered on and off; but he was always modest and self-effacing, and died in relative obscurity.

Robert Gore-Langton presents an attractive picture of Sherriff, whose papers he has studied exhaustively in the Surrey Record Office. An experienced drama critic, he is particularly illuminating on the theatrical history of the play. In a final chapter he traces the changes in interpretation with each major revival of Journey’s End since the 1950s. He ends with the 2011 West End production, directed by David Grindley, who is quoted at length, discovering profundities in the clownish Lieutenant Trotter, and demonstrating that despite Sherriff’s conservative adherence to values rooted in Edwardian England, the play, in the hands of a penetrating director, still has new things to tell a 21st-century audience. No other British play about the Great War by a veteran has supplanted it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £9.89. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in