George Brandis

In a year which saw a seemingly endless stream of books of the ‘where the Labor party went wrong’ variety — admittedly a vein rich with material — the book that defined the times came from the other side of politics: Nick Cater’s The Lucky Culture. Elegantly written, provocative and analytically ruthless, Cater takes aim at a whole herd of left-wing sacred cows.

Also from my side of politics, it is a while since Australian publishing has produced a book as charming as Heather Henderson’s memoir, A Smile for My Parents. Her account of life at The Lodge as the daughter of Menzies is both a portrait of a happy family and an evocation of a more gracious age. It reminds us of what a Titan Sir Robert Menzies was — our greatest Prime Minister by far.

My fascination with the politics of 19th century England was nourished by two marvellous new works. Perilous Question: The Drama of the Great Reform Bill 1832 tells the tale of the reform of the franchise by the government of Early Grey. It is high stakes political drama, replete with thrilling Parliamentary theatre, intrigues between Prime Minister and King, and convulsive general elections. Lady Antonia Fraser blends scholarship and storytelling, and brings a practised eye to her portraits of the leading characters of the time.

Douglas Hurd has made a postpolitical career as a serious biographer — his life of Peel is a model of its kind — and has now given us a new biography of Disraeli. It is a gem. Erudite, iconoclastic but in the end affectionate, it provides a new take on this enigmatic personality who was Queen Victoria’s favourite Prime Minister. And, as you follow Hurd through Disraeli’s show-stopping career, I challenge you not to be reminded of Christopher Pyne.

George Brandis is the federal Attorney General and minister for the arts.

Leigh Sales

Of all of the books I’ve read this year, the only one I intend to reread is Lean In by Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg. It is a modern, pragmatic take on women in the workplace, full of practical ideas about increasing female representation at executive levels without being hectoring or ideological. This Town by Mark Leibovich, lifting the lid on Washington’s insider culture, was overhyped but deliciously gossipy. Difficult Men by Brett Martin, on how some of the best TV of the past 20 years was created, including The Sopranos and The Wire, is a fascinating insight into the big personalities in writing rooms and on sets.

In fiction, Lionel Shriver’s Big Brother explores a sister’s love for her morbidly obese brother in a way that is both funny and horrifying (although the ending was deeply flawed). The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion is a charming light read. My summer reading will be The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt and The Narrow Road to the Deep North by Richard Flanagan.

Leigh Sales is host of the ABC’s 7.30.

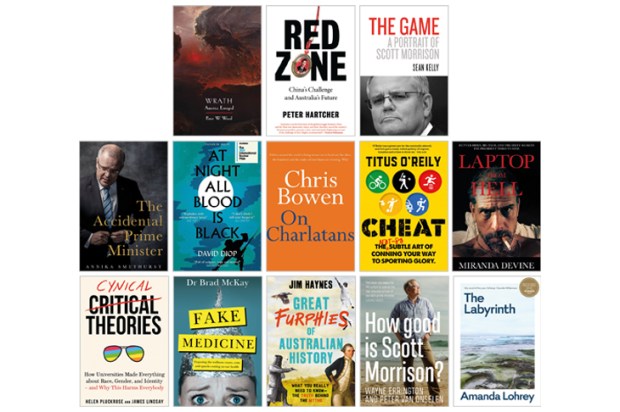

Chris Bowen

2013 for me has been the year of John Boyne. It has taken me a little while to catch up with the works of this forty-something Irish author, but he has joined the ranks of my favourite modern fictional authors.

With the thousands of words that have been written about the Holocaust, it is difficult to imagine that a new novel could add much. But The Boy in Striped Pyjamas certainly does. It has an ending which left me breath-taken and moved.

The House of Special Purpose beautifully shifts between 1980s London and 1918 Russia to weave a compelling story with a twist which, although more predictable than in The Boy in Striped Pyjamas will stay with you. The Absolutist is another carefully crafted story of war, love and secrets which is deeply moving. Boyne’s latest work, the recently released This House Is Haunted sits expectantly on the Christmas reading list.

Chris Bowen, a former treasurer and immigration minister, is federal Labor’s treasury spokesman

Derek Parker

One of the most important books of the year is also one of the best reads. Henry Reynolds’s Forgotten War is a carefully researched examination of the violent conflicts between indigenous peoples and settlers in the early part of Australia’s white history, and although Reynolds looks at the legal issues and historical significance he retains a focus on the human dimension.

A different type of enjoyment comes with Graeme Simison’s The Rosie Project, a lighthearted novel centred on a fellow who knows a lot of scientific facts but not much about how humans work — until Rosie begins to blunder through the pages. Simison is never going to win the Booker Prize but, well, so what?

The winner of the Trees Are Dying for This Award is The Rudd Rebellion by Bruce Hawker, who is vaguely remembered as an adviser to Kevin Rudd — in other words, an Assistant Loser. The book purports to be a diary account of the run-up to the 2013 election, but is little more than an extended self-indulgence. It does, however, raise one interesting question: how do some books get published?

Derek Parker is a regular book reviewer for The Spectator Australia.

John Hirst

I made the mistake of thinking that Anna Goldsworthy had only one book in her. She is a concert pianist so it was not altogether surprising that could write a good book on her musical education, Piano Lessons, especially since she had her Russian teacher to entertain and enlighten us. But now she has written a book on giving birth which catches the crazy, overwhelming, boring (to outsiders) love of mother for new child in the womb and outside it. Don’t be misled by the title Welcome to your New Life into thinking this is a guide to migrants.

And then she turned social commentator and lifted misogyny out of partisan politics where Julia Gillard placed it and discussed how gender now plays in the culture in Unfinished Business: Sex, Freedom and Misogyny. Like John Howard for the Liberal party, she wants feminism to be a broad church and more willing to be funny and sexy. She has her own sharp, fresh language to talk of sex. And she is still playing the piano!

John Hirst has written many history books, the most recent being Looking for Australia: Historical Essays.

Keith Windschuttle

The best Australian read of 2013 was Nick Cater’s The Lucky Culture. Often comical and always illuminating, he points out the disastrous directions our ‘progressive’ leftist ruling class is taking us. Cater is up there with Mark Steyn as an observer of contemporary political fashions and follies. He was the first to point out that we now have nine (yes, nine) human rights commissions for a population of 23 million people. This joke is not funny.

Ian McLean’s Why Australia Prospered is not only the best work of economic history this year, but in many a year. He shows our classical liberal focus on comparative advantage in wool and gold made Australians the richest people in the world in the 19th century, but also that protectionism in the 20th helped build the industry crucial for our defence in the second world war.

The most shocking book of the year is Hal Colebatch’s Australia’s Secret War: How Unionists Sabotaged Our Troops in World War II. I never knew until I read this manuscript that the trade union movement had stooped so low when Australia was fighting for its life. Most of the romantic leftism of my youth was disabused long ago, but I still found myself stunned by Hal’s findings. This book will change many readers’ idea of what it is to be Australian.

Keith Windschuttle is editor of Quadrant and author of The Fabrication of Aboriginal History.

Gideon Haigh

Another book about the wilful obscurity of academic language? Yes, and Learn To Write Badly may be the freshest and cleverest ever, because Michael Billig is writing from the inside as a professor of social sciences at Loughborough University: he knows all the tricks and poses, and examines them with a mix of cool detachment, warm humour and suitably dense footnoting.

Vasily Grossman’s An Armenian Sketchbook looks slight alongside his epic novels Life and Fate and Forever Flowing, but its acutely personal responses to people and landscape are revelatory. His account of looking for a toilet in Yerevan is also hilariously sphincter-tightening.

As for underwhelming experiences, I dutifully read Colleen Ryan’s Fairfax: The Rise and Fall and Pam Williams’s Killing Fairfax and began losing the will to live. Fairfax writers writing about Fairfax? They’re like being stuck in an endlessly circular conversation with you an unhappy person about a dysfunctional relationship you know they will somehow never leave.

Gideon Haigh is author of 29 books, including Uncertain Corridors: Writings on Modern Cricket just out.

Mark Scott

The once-in-a-decade emergence of Donna Tartt is a treat. The Goldfinch is a sweeping, character-driven literary novel where you simply get lost in the story. She is such a lovely writer, but with a driving sense of narrative — the only problem is you want to read it too quickly. For those of us fifty-somethings, The Interestings by Meg Wolitzer helps you appreciate the sustaining nature of those oldest friendships, made in our teens and early twenties — those who have made the journey with us.

For non-fiction, let me cheat and suggest a quasi talking-book. Get the DVD of Kerry O’Brien interviewing Paul Keating and just listen to the great self-described ‘maddie’ explain his childhood, his mentorship by Jack Lang and the epic battles for reform and change in Labor party and the Australian economy. A century of Australian federation has not delivered a better phrase-maker. It is the best political memoir never written.

Mark Scott is managing director of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

Stephen Romei

Two works will dominate the important prizes for Australian fiction next year: Eyrie, Tim Winton’s funny, cranky, class-conscious, prosperity-puncturing chronicle of one man’s midlife collapse and possible rejuvenation, and The Narrow Road to the Deep North, Richard Flanagan’s profound, empathetic (but not necessarily sympathetic), myth-shaking masterpiece centred on the Thai-Burma Railway and a Weary Dunlop-like figure.

Two works that should challenge them are J.M. Coetzee’s strange, beautiful, chilling The Childhood of Jesus, a novel that recasts the refugee question, and Nicolas Rothwell’s brooding Belomor, a fiction-memoir that feels the absences in the world and merits its author comparison with Bruce Chatwin and W.G. Sebald. Speaking of fiction-memoirs, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s six-volume autobiographical novel My Struggle is one of the most absorbing literary projects of recent times, one that has seen the Norwegian writer dubbed the Scandinavian Proust. The first two volumes, A Death in the Family and A Man in Love, came out in English this year and the third, Boyhood Island, is due on April. At the other end of the spectrum, words-wise, is Shaun Tan’s picture book Rules of Summer, a surreal, haunting and random (to use my eight-year-old’s highest approbation) tale of two boys and a season of surprises.

Stephen Romei is literary editor of the Australian.

Stephen Loosley

Inside the Beltway is given new meaning by Mark Leibovich’s hilarious yet insightful This Town, which focuses upon the self-obsessed political, media and lobbying tribes of Washington DC. This Town begins at the funeral of legendary anchor of NBC’s Meet the Press, Tim Russert, but does not finish with an index, thus obliging all the self-important Washingtonians in the book to buy it. Two books changed my mind about major political figures. The first was Rana Mitter’s China’s War with Japan (1937-1945) which shifted my view of Chiang Kai Shek. The other is Jeffrey Frank’s Ike and Dick, which cast Richard Nixon in a much more favourable light as Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Vice President. Michael Fullilove’s splendid effort, Rendezvous with Destiny, about Franklin Roosevelt’s wartime envoys to London deserves mention.

Easily the most disappointing book of the year was John Le Carre’s A Delicate Truth, which is as bleak as the Gibraltar landscape on which it is set and could easily have been written by Alec Leamas after a bender.

Stephen Loosley is a former Labor senator and national president of the ALP.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.