It’s a fact that most ministers are most scared, not of their political rivals but of their civil servants. Ministers know that if they cross civil servants, all of their foibles may soon end up in print. It’s one reason why politicians so often repeat the mantra ‘Our civil service is the best in the world,’ so as to keep on their good side.

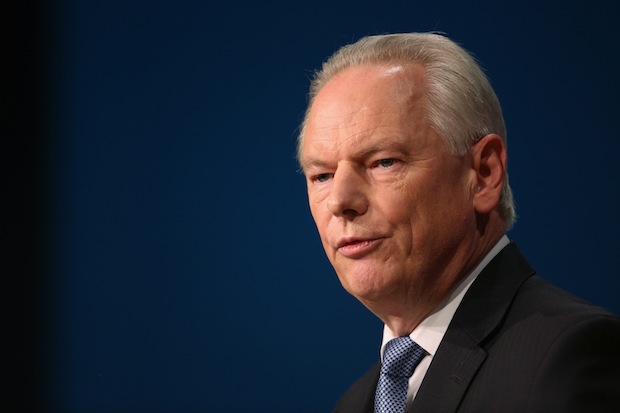

One man stands out: Francis Maude, Minister for the Civil Service, has spent most of his political life telling his party why it doesn’t work as a modern institution and now he’s taking on the civil service with equal frankness. This approach has not gone down well. Mandarins have pushed for Maude to be reshuffled, parodied his proposals and wheeled out the old guard to attack him. The latest step was Lord Butler, a former head of the civil service, taking to the airwaves to condemn Maude for not understanding leadership.

Much like the National Health Service, the civil service demands submission to the idea that it embodies all that is best about Britain. Those, like Maude, who refuse to play along with this are treated as heretics. As with the NHS, there are patches of excellence in the civil service and some brilliant people. But there is too much mediocrity, acceptance of second-rate service and glossing over of problems. Those who want to hold individual officials to account are treated as pariahs. Too often the civil service seems to aspire to the prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages: power without responsibility.

Whitehall has also been infected by the worst of the New Labour public-service culture. Under Sir Gus O’Donnell, the last Cabinet Secretary, a fear of elitism developed that amounted to a rejection of excellence. One minister was shocked when civil servants refused to tell him what universities job applicants had gone to, on the grounds that it could prejudice his decision. The spin culture has been absorbed too. Jeremy Heywood, the Cabinet Secretary, has a more active media operation than most ministers.

But the reason that the civil service is so sensitive now is that reform is a genuine possibility for the first time in decades. Any programme of radical reform needs cross-party support. But until recently there was never a chance of achieving such support: it wasn’t in the interests of one or other party to agree.

From opposition, the Tories screamed ‘politicisation’ every time Tony Blair considered changing how Whitehall works. But now all three parties believe that they have a chance of being in power after the next election, and therefore have an interest in reform. Tellingly, a former Tory and a former Labour frontbencher, Nick Herbert and John Healey, have come together to form a cross-party group to push for radical reform of the civil service. It will launch in January.

The old Tory opposition to change wasn’t just borne out of political opportunism. They genuinely believed that the only problem with the civil service was its political masters. When Maude headed the implementation unit in opposition, he refused to accept that there might be any fundamental flaws with the civil service. But having been in office, ministers now know that the civil service machine is broken. Those who are in government again having served under the last Tory Prime Minister agree that standards have fallen markedly. Ministers find their own names misspelt in letters, there are factual errors in answers to parliamentary questions and grammatical mistakes in press notices. It has become normal, even during the busiest times, for civil servants routinely to take Fridays off, and work from home on other days.

So why has no one cracked the whip? Well, the civil service still has enough alpha officials to service the needs of the most important members of the government. In three of the great offices of the state, the quality of civil servants remains high. The mandarins are canny enough to know that maintaining this standard is crucial to persuading the Prime Minister that there is no need for radical reform of the civil service.

This tactic has largely succeeded. David Cameron is an establishment figure and temperamental conservative and has shown no great enthusiasm for reforming Whitehall. Even in the face of this public onslaught against its minister for the civil service, No. 10 is failing to throw its weight behind Maude. This fits a pattern. Cameron’s chief of staff, Ed Llewellyn, instinctively takes the side of the civil service in any dispute between them and political appointees.

To some, all of this complaining is undignified. Grandees sniff that only a bad workman blames his tools. But this gets things backwards. It would be more accurate to say that a bad workman doesn’t notice his tools are blunt. It is those secretaries of state who have been happy simply to preside over their departments who have no complaints about the civil service. It is those who have tried to do something — think Michael Gove and Theresa May — who have the most.

Fittingly, it is Universal Credit, the government’s most ambitious reform programme, which is the cause of the current tensions. The mandarinate are objecting to the idea that the permanent secretary of the Department of Work and Pensions should be held accountable for its implementation. To be sure, Universal Credit is a complex project that relies on information technology, a traditional public-sector weakness. But it should not be beyond Whitehall’s capabilities to introduce it.

Too many people, though, think that is just the way things are. Alistair Darling told Iain Duncan Smith in the House of Commons recently, ‘I looked at something like Universal Credit some 12 years ago, and I was advised then that it was technically very difficult, if not impossible, to implement it at anything like an acceptable cost and that whatever the cost I was quoted, it was likely that it would end up costing an awful lot more.’ Darling seemed to regard this as an argument against Universal Credit rather than for civil service reform. If a bureaucracy can’t deliver, then it doesn’t work.

Even if the defenders of the status quo defeat Maude, change is coming. In the same way that those who had served in Heath’s government knew that national renewal couldn’t happen without facing down the unions, today’s ambitious ministers know that they must deal with Whitehall’s problems before they can fix the country’s. Civil service reform will be unfinished business for the next Tory Prime Minister.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in