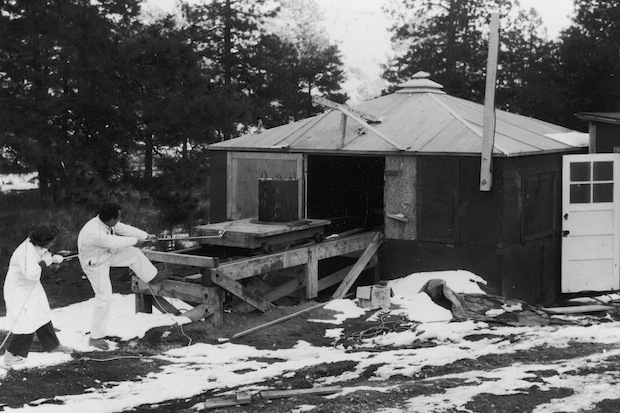

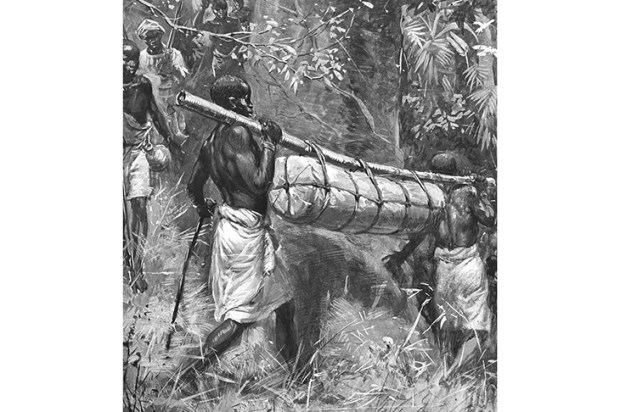

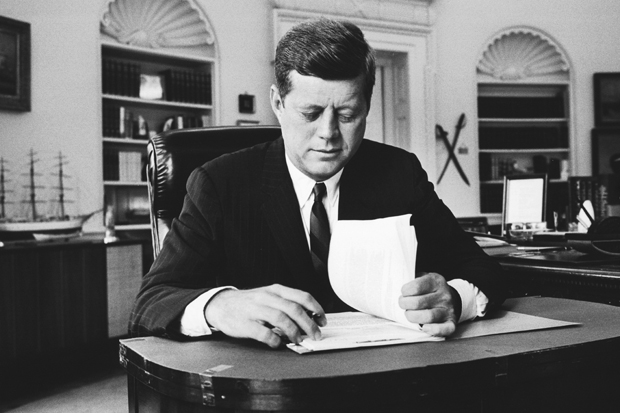

At the dark heart of this dark book is a startling fact: Joseph Conrad was employed to steam up the Congo river by the same company, Union Minière du Haut Katanga, that later shipped uranium from the Congo to the US, where it was used to make the bombs that devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £15.99, Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in