I wish I were a religious conservative: the field’s wide open. It must be dispiriting for believers to encounter so little intelligent support for belief. It’s certainly infuriating for us non-believers, because there’s hardly anyone left who seems capable of giving us a good argument. In search of a stimulating conversation about religion, we are reduced to arguing with ourselves.

Which, still seething at a Spectator article purporting to be a serious examination of the case for miracles, I shall now do. I cannot argue with Piers Paul Read because he never produces an argument to answer. The magazine tagged his piece ‘I believe in miracles’, which was accurate because the essay was not a reasoned case; it was simply an attestation.

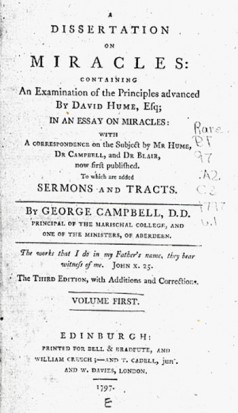

What drew me into it was the implicit boast thatMr Read was about to answer the greatest British philosopher of all time, the 18th-century Scot David Hume. Indeed he refers to Hume’s essay ‘On Miracles’ as the leading case against the veracity of miraculous occurrences. But he doesn’t explain Hume’s argument. He simply asserts that it has been ‘refuted’ (he means ‘challenged’, or ‘countered’) by philosophers like Anthony Flew and the Catholic G.E.M. Anscombe. He adds that C.D. Broad ‘made mincemeat’ of it.

Mincemeat of what? I cannot suppose that Piers Paul Read does not understand Hume’s ‘On Miracles’, because its reasoning is stunningly simple and can be summarised in three sentences. So let me do Read’s job for him:

1 A ‘miracle’ claims to be a divine intervention which temporarily overturns a law of nature, so faced with such a claim we must weigh our habitual assumption — massively and anciently supported — that the laws of nature always hold, against a single report that they have been overturned.

2 People are notoriously deceitful, gullible and liable to mistake what they see, so it will always be more rational to conclude that the evidence for a miracle is unreliable than that the laws of nature have been overturned.

3 It follows that no person relying on reason alone can ever conclude that the evidence for a miracle outweighs the evidence against it.

Let’s hear Hume himself speak. To conclude (he allows) that apparent eyewitnesses were under a misapprehension may strain credulity, but…

When anyone tells me, that he saw a dead man restored to life, I immediately consider with myself, whether it be more probable, that this person should either deceive or be deceived, or that the fact, which he relates, should really have happened. I weigh the one miracle against the other; and according to the superiority, which I discover, I pronounce my decision, and always reject the greater miracle. If the falsehood of his testimony would be more miraculous, than the event which he relates; then, and not till then, can he pretend to command my belief or opinion.

Hume goes on to remark that the world’s religions support their central claims with minor claims to miracles. But these religions believe their rival religions’ central claims to be false. If we are to follow one religion, we must discard as false the miracles claimed by the others. From the start, therefore, any Christian, Muslim, Hindu or Jew has to believe that the witnesses to many miracles were fooled, even if the witnesses to his religion’s miracles were not.

Having explained the argument Read is rejecting, I shall now attempt the second task he left unaccomplished, and point to weaknesses in Hume’s reasoning. I can think of two, of which the second is more interesting.

The first is that, on one interpretation, Hume’s argument is circular. He starts from the premise that we have overwhelming evidence that natural laws cannot be overturned; he goes on argue that this accumulated evidence must outweigh any isolated report of the overturning of a natural law; it follows, he says, that we can never rationally believe such a report; and he concludes that… er, natural laws cannot be overturned. Tautological? I have to say that Hume lays himself open to the charge by suggesting that his is a logically necessary case, rather than an empirically compelling one. Were he to restrict himself to noting that the evidence of every generation since the dawn of man, in innumerable instances, is most unlikely to be outweighed by the claims of a handful of witnesses in a single instance, he would be on surer though less philosophically exhilarating ground.

The second objection is this. Even if accepted on its own terms, Hume’s essay does not prove that no miracle could ever occur. It proves that no claim to a miracle could be reasonably believed. Hume strikes me as curiously unmindful of the distinction between saying that on the balance of probabilities a claim is false, and saying the claim must be false. A court of law, finding a prisoner guilty beyond reasonable doubt, does not exclude the possibility that he is innocent; but deems the possibility negligible. Miscarriages of justice occur, even in cases where the agents of justice reached their conclusion reasonably.

To caricature the Scottish philosopher, Hume is saying to God, ‘You cannot perform a miracle, Lord, because any report of it must logically be discredited’ — to which God might reasonably reply ‘Try me, David’; or, more patiently, ‘You may be right, Mr Hume, that no reasonable person acting on reason alone would believe I rolled away the stone, but that does not mean that I did not roll away the stone.’

…which brings us, I believe, to an interesting truth contained in Hume’s essay — and a thought on which he does touch. In remarking that ‘no testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle, unless the testimony be of such a kind, that its falsehood would be more miraculous than the fact which it endeavours to establish’, he makes the point that the act of believing in a miracle is, in itself, a minor miracle, for in accepting a miracle the believer must forsake the laws of probability.

You could put it more simply: one needs faith before one can believe in miracles. A claimed miracle cannot be a justification for faith, but faith can justify believing the claim. Herein lies the theists’ own circular argument: to have faith, you must have faith; to make the leap, you must make the leap.

There we are, Piers Paul Read: your job done for you. A pity it’s all bunkum.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in