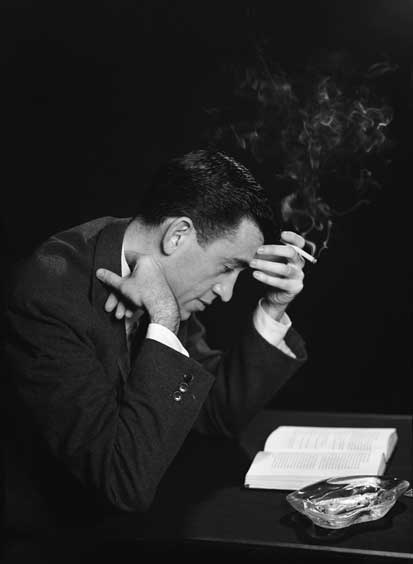

Philip Ziegler is best known for his biographies, often official, of politicians, royalty and soldiers. They include Harold Wilson, Edward VIII and Louis Mountbatten, whose correspondence he also edited. What has driven him to write about an actor — and one whose life has been fully covered in so many biographies, the most recent being Terry Coleman’s in 2005?

I take it he knows little of theatre on the inside and has had to base his book on the notoriously unreliable gossip of actors, not the least of whom was Olivier himself, a supreme fantasist. I am not even sure that Ziegler is a theatre buff. But there must be something which draws him to the subject, and it is gradually revealed in the course of the book: his approach is to treat Olivier as if he were a soldier or politician and not as an actor at all.

To this end he concentrates on Olivier’s time as director of the National Theatre. He is very selective of the performances he chooses to focus on — ignoring Olivier’s wonderful 1959 Coriolanus, for instance — but his approach keeps the narrative going. The underlying purpose of the story turns out to be not the deification of an actor but the honouring of a leader. In an afterword he draws a detailed comparison between Olivier and Mountbatten and sees them both, like Noël Coward’s captain in his wartime epic In Which We Serve, as the epitome of the stiff upper lip: ‘A tight ship is a happy ship.’

You realise this is where he has been going from the beginning. He has not drawn back from the many flaws in his subject — the vanity, the self-centredness —and indeed has used them to highlight the heroic figure that eventually emerges. I have not read Ziegler’s other books, but I would guess that it is a technique he has used before. It works very successfully in making us look at the well-known life afresh and with renewed respect.

I worked with Olivier on an almost daily basis for two years in the run-up to, and first two seasons of, the National Theatre at the Old Vic, but I cannot claim that I ever got close to knowing him. He had a combination of ruthlesssness, of inner steel, and the worst kind of theatrical campery which was irresistible. It was an exhilarating time, and it was never less than a pleasure to work for him, and with him. I only directed him once — as Captain Brazen in The Recruiting Officer — and though our relationship was perfectly amicable he probably thought my methods arty. He joined in the improvisations in rehearsal but went his own way in performance.

He could be capable of grossness — at one point he licked Melinda’s hand for no apparent reason and I hadn’t the courage to try and stop it. The audience loved it. At the dress rehearsal, when the younger actors had made themselves as butch as possible with heavy brown make-up, Olivier appeared with a face painted the palest pink. ‘You will see, I shall get all the laughs,’ he said — and so it proved.

His own direction often had misguided starting points. He saw Three Sisters as a call to arms for the Russian Revolution. At the end, the sisters strode off stage to the sound of the Internationale. To be fair, some critics bought the interpretation.

The flaws in his acting, as in his character, were negated by the intensity of his energy, which all who worked with him felt drawn towards. He was unquestionably the right man at the right time to open the National Theatre, and he was loved and respected by the whole staff, not just the actors. It is this which Ziegler makes the centre of his approach, and it works well. I don’t know whether I buy the parallel with Mountbatten, but it is persuasively argued.

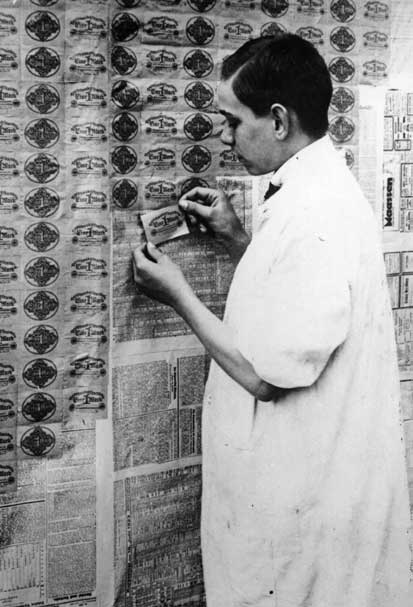

Ziegler’s lack of theatre knowledge, however, means there are many factual errors. The illustration captioned as Olivier and Vivien Leigh in Fire Over England is obviously of the 1940 New York production of Romeo and Juliet, Keith Michell, not Harry Andrews, was the Macduff in the 1959 Macbeth, John Burrell not Tyrone Guthrie directed Arms and the Man at the Old Vic in 1945, Michael Redgrave was not replaced during the rehearsals of The Master Builder and Olivier did not take over till the following season.

Ziegler’s jumps in chronology are often misleading. About Olivier’s decision to play in The Entertainer he writes: ‘The Court, under the direction of that ardent Brechtian William Gaskill, became not merely renowned for the spare, integrated ensemble acting…’ as if I were running the theatre at that time. In 1957 I was a young, out-of-work director looking for a job. I did work as an assistant at the Royal Court later in the year, but did not run it till 1965. At the time of The Entertainer it was run by its great founder, George Devine, and his associate, Tony Richardson, who directed Olivier as Archie Rice and so turned the latter’s career — and arguably that of the British theatre — in a new direction.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in