Last month, David Cameron convened a meeting of his most important advisers at Chequers. The Prime Minister, the Chancellor and the Conservative party chairman were all present, but there was little doubt who was in charge. The Australian strategist Lynton Crosby was dominant, doling out orders and drawing up ‘action points’. One of those in the room recalls: ‘Lynton was fantastic. He made sure there was an agenda, that everyone stuck to it.’

It might seem odd for an Aussie to be telling the British PM what to do, especially in this most English of settings, but it’s mainly because of his nationality that the ‘Wizard of Oz’ gets to call the shots. His reputation as a toughie from the outback gives him the authority to speak plainly and issue orders.

But Crosby is only part of a wider takeover of our public life by English-speaking ‘tough guys’ from the ‘dominions’. A South African, Ryan Coetzee, directs the political strategy of the Liberal Democrats. A Canadian, Mark Carney, has now become governor of the Bank of England, and with so many powers at his disposal that he can be seen as the single most important figure in our economy. These three, Crosby, Coetzee and Carney, will be critical in determining the state of the country, and the national mood, come the next election.

Professionals from the colonies are everywhere once you start looking. The England cricket team may have shredded our nerves at the weekend but its win in the first Ashes Test has boosted our spirits. Much of the credit for this victory rests with the side’s Zimbabwean coach, Andy Flower. And the successful British Lions tour of Australia was masterminded by the New Zealander Warren Gatland, who is also the Welsh head coach.

From Westminster to Lords, from Threadneedle Street to the try line, a theme is emerging. The Dominions are rapidly gaining dominion — over us.

You need to go back to wartime Britain, 1940, to find an era where there was such an influential group of the Monarch’s overseas subjects. Then, the Australian prime minister Robert Menzies and the South African Jan Smuts were attending Winston Churchill’s War Cabinet, while the Canadian Lord Beaverbook was in charge of ensuring that enough planes were in the air to win the Battle of Britain. The work of the new colonials is obviously not as important as war work, but their rise to prominence does tell us something about this country, its flaws and its place in the world.

These new colonials are filling an intellectual gap in British public life created by the return of the old (and not much improved) ruling elite. They bring with them a sense of the frontier spirit, something which has been largely lost from Britain since the end of empire. Indeed, in many ways, they represent the discipline, ingenuity and confidence that were once this nation’s hallmarks.

An ability to transcend class is particularly useful in the modern Conservative party. Every time an Old Etonian or Notting Hill friend of Dave is recruited into Downing Street, backbenchers cry foul. So the fact that Crosby is Australian is vital. It also makes him a perfect go-between. Tory backbenchers who have strained relations with Cameron’s gilded circle talk to Crosby when they want to get a message to the PM.

Tellingly, Cameron and Osborne now use Crosby to make the case for the leadership’s political strategy to their MPs. As one of the Prime Minister’s inner circle puts it: ‘If David Cameron or George Osborne present their strategy for dealing with Ukip, then the backbenches may be inherently suspicious. But they’ll be far more receptive if it comes from Crosby.’ The fact that Crosby is a professional campaigner also helps: he’s the man who took John Howard to four successive Australian poll victories, twice got Boris Johnson elected Mayor in Labour London, and prevented the Tories from melting down in 2005.

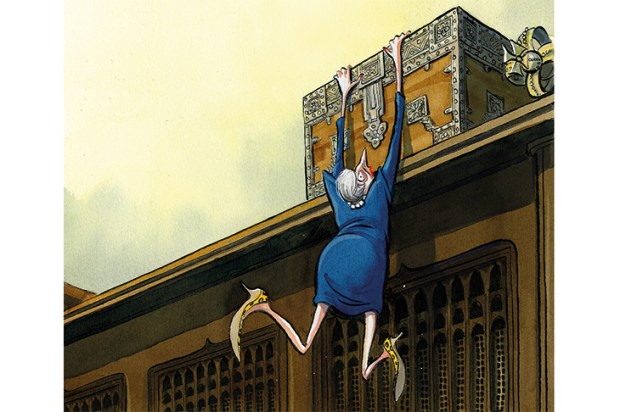

Crosby’s hard-scrabble Antipodean background gives him an aura of toughness that others are prepared to defer to. His injunction to ‘get the barnacles off the boat’ is treated as if it had come down from Sinai, not Sydney.

Even the current row over whether or not Crosby played any part in the government’s decision to drop plans for plain packaging for cigarettes hasn’t damaged his standing in the Tory party. It also hasn’t bothered his Aussie compatriots. Crosby had a table at a recent dinner at Lord’s to honour the memory of Sir Donald Bradman, and his Australian friends who were present wouldn’t let the packaging business drop. To the amusement of his British guests, they kept asking him, ‘Do you want a cigarette, mate?’

Crosby’s Liberal Democrat counterpart, Ryan Coetzee, is nowhere near as controversial a figure, but he does represent a break with Liberal Democrat orthodoxy. He is a broad-shouldered man who looks like he’d be useful in a rugby scrum — the opposite of the caricature of a weedy, yoghurt-eating Lib Dem.

Coeztee’s job is to whip the Liberal Democrats into a disciplined, professional political party. It is no easy task. His predecessor, the British liberal intellectual Richard Reeves, found the party infuriatingly resistant to this change. He joked to friends that if the party had been irritated by him, they were going to be driven mad by this strict Saffer. Coetzee had, after all, cut his political teeth campaigning against the ANC.

But the Liberal Democrats have proved remarkably open to Coetzee’s instruction. The curmudgeonly Lib Dem peer Tom Greaves has been left complaining that the party is treating Coetzee as ‘the new risen saviour’. Meanwhile, Coetzee has been busy explaining in his distinct Cape twang precisely how the Liberal Democrats appeal to the one-in-four voters who his research shows are open to supporting them at the next election.

Crosby and Coetzee both exercise their power behind the scenes. But Carney is very much a front-of-house man: the first foreigner to run the Bank of England, with film-star looks and a high society (English) wife to boot. While Sir Mervyn King was easily identified as an owlish academic, Carney (whose background is in investment banking) is seen as a man of action. But that’s part of the magic: all colonials are seen in Britain as men — and women — of action.

When David Cameron considered hiring an American, the former New York and Los Angeles police chief Bill Bratton, to run the Metropolitan Police, there was a slew of objections. The Home Secretary, Theresa May, eventually persuaded Downing Street that it would be inappropriate to have a foreigner commanding London’s police force. But when George Osborne indicated that he was attracted to the idea of recruiting Carney, no one complained about the prospect of a Canuck setting our interest rates or deciding whether or not Britain should indulge in another round of quantitative easing.

Given that the Governor of the Bank of England wields much more power than the head of London’s police, the lack of controversy over his appointment is striking. But much of this can be explained by the fact that Brits don’t quite see Canadians as foreigners — more as cousins with some funny habits. They have the same head of state, after all. Indeed, a former editor of The Spectator, John Buchan, went on to be Canada’s governor-general. Had Cameron wanted to give a Mountie the top job at Scotland Yard, one doubts that there would have been such a fuss as there was over Bratton.

The popularity of the new colonials reflects a certain uncertainty in British masculinity; it is no coincidence that the most prominent among them are male. Once, Westminster was full of young Britons who had proved themselves in the far corners of the Empire. But now it is full of those who have glided from quad to quad, and are only too aware that they grew up on a gap year and not the North-West Frontier.

This is even more pronounced in sport. When England fell to the bottom of the Test Match pile, it was a Zimbabwean they turned to. Duncan Fletcher was hired having made his views known on the softness of the English county system. When he was given the England job, his remit was to make the team a hard, competitive outfit. It was a task considered beyond any Englishman.

Fletcher led England to the first Ashes win in 15 years. But eventually the passage of time and the disenchantment of various players did for him. The England Cricket Board thought it was safe to turn back to an Englishman and gave the job to the Sussex coach Peter Moores. The result: disaster. Moores was gone within two years, with a dressing-room revolt and a series of defeats under his belt.

In this crisis, whom did England turn to? Another Zimbabwean, Andy Flower. The tough-as-teak Flower turned England around again.

It is hard to imagine any British political party hiring a Frenchman or an Italian to run their election campaigns. The more complicated the world is, the stronger the bonds of language and the common law become. In the end, culture trumps geography.

Which leaves a question hanging: if our political and sporting elite are so keen on recruiting those from the Dominions, why should we allow anyone from Greece to come and seek work in Britain while making it harder and harder for Canadian architects and Indian businessmen to move to these shores?

The new colonials tend to share this puzzlement. Before he was recruited by No. 10, Crosby conducted a whole series of polls for a client about what arguments are most effective in persuading the public that Britain needs a very different relationship with the EU. It would be particularly fitting if the new colonials used their growing power in British life to raise our sights from the Channel to the oceans beyond.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in