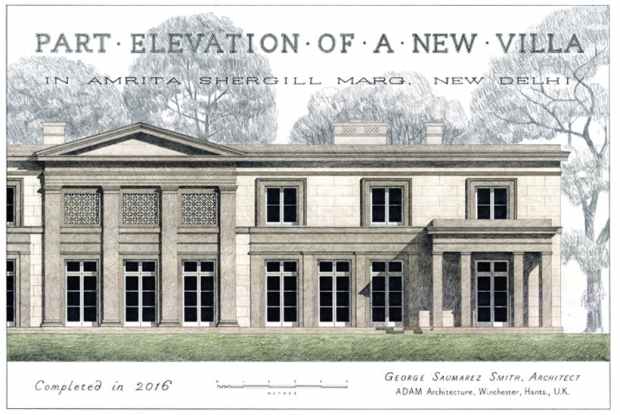

On the outskirts of La Chaux-de-Fonds, an industrial town in the Swiss Jura, stands one of the most beautiful houses I’ve seen. Elegant and understated, La Maison Blanche is the kind of house you dream of living in. Wide windows overlook a wooded valley. The rooms are bathed in silver light. The ambience is serene and timeless, more like a temple than a townhouse. You’d never guess the man who built it was the bogeyman of modern architecture — the man who began a movement that replaced terraced streets with tower blocks. In this lovely house, and the art-nouveau villas he built beside it, you can see the traditional architect Le Corbusier could have been.

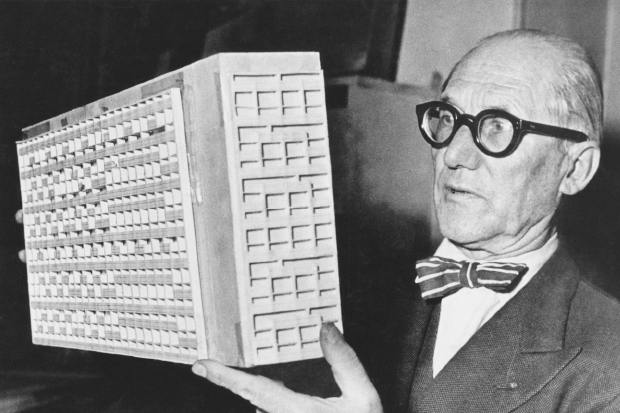

Le Corbusier was born here in La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1887. Christened Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, his birthplace is a short walk from La Maison Blanche. A modest plaque marks the spot, outside a nondescript apartment block. It’s a perfunctory tribute, inscribed with his name and not much else. ‘Laisse Beton!’ someone has scrawled across it. ‘Leave Concrete Alone!’ It feels like a fitting epitaph. Countless cities bear the scars of Le Corbusier’s love of concrete. Half a century since his death, he remains the architect conservatives love to hate.

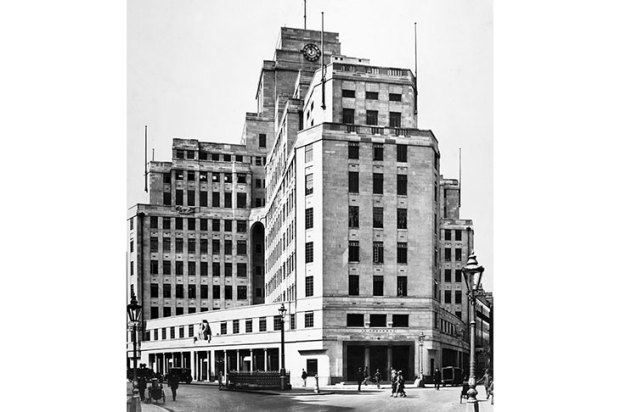

Le Corbusier moved to Paris in 1917, where he adopted his famous nom de plume. ‘A house is a machine for living in,’ he declared. ‘A curved street is a donkey track — a straight street is a road for men.’ It’s hard to think of a manifesto less in tune with British tastes. Le Corbusier still personifies the great divide between British and Continental attitudes to modern architecture. In Britain, our clumsy copies of his high-rise housing projects are derided as ugly eyesores. In France and Germany, his Unités d’Habitation are revered. It’s easy to see why we don’t like them. Admired in Europe and condemned in Britain, his Grands Projets symbolise the paternalism of the European superstate.

The irony is, Le Corbusier’s Eurocentric building style actually evolved here in his native Switzerland — the most Eurosceptic country on the Continent. And although he left La Chaux-de-Fonds when he was 30, his unfashionable hometown had an enduring influence on his work. Indeed, if he’d been born anywhere else, it’s quite possible that the history of modern architecture might have been completely different. For La Chaux-de-Fonds is unlike any other town in Switzerland — or Europe for that matter. As a tourist destination it’s humdrum and (by Swiss standards) down-at-heel, but as an architectural curio, it’s a conurbation without equal.

Until 1857, La Chaux-de-Fonds was Prussian. When the town burnt down in 1794, the Prussians rebuilt it on a geometric grid. Broad boulevards were more accessible in heavy snow (at an altitude of 1,000m, winters here are fierce) and in the 19th century these dimensions made it an ideal centre for the Swiss watchmaking industry. These watchmakers worked at home, rather than in factories, so apartment blocks were built some way apart, with extra floors and extra windows, to maximise the scarce sunlight they needed for their work. No wonder La Chaux-de-Fonds feels so futuristic. Tall buildings with lots of glass and lots of space between them — these were the principals Le Corbusier applied throughout his life.

Le Corbusier’s father was a watchmaker and he would have become a watchmaker too, but his eyesight wasn’t good enough, so he ended up at the local art school. Here, he met a dynamic teacher, Charles L’Eplattenier, whose art-nouveau designs now adorn the town’s Musée des Beaux Arts. L’Eplattenier encouraged Le Corbusier to become an architect. His first three houses, built in partnership, stand on a steep hill opposite La Maison Blanche. La Maison Blanche was the first house he built alone. It was a present for his parents. They loved living here, but the upkeep proved too costly, and in 1919, after seven years, they had to sell up and move out. The house remained in private hands until 2000, when it was bought by a local trust, who renovated it, and reopened it in 2005 as a cultural centre and museum. Decorated with photographs, books and artefacts, it’s an undiscovered gem.

The last house Le Corbusier built in La Chaux-de-Fonds was the Villa Turque, in 1917. Like La Maison Blanche, it’s neoclassical, with scant hint of his subsequent modernism. It’s a splendid building, but it came in at over twice the budget, and Le Corbusier ended up in a legal dispute with the owner. Fed up, he left for Paris and his career took a different course.

The five houses Le Corbusier left behind in La Chaux-de-Fonds are mementos of what might have been. What if he’d stayed here, and carried on building in the same unobtrusive style? What if he’d fallen out of the window at La Maison Blanche, and landed on his head? Would we have been spared the monstrosities that blight our modern cityscapes? Or would some other architect have opened the same Pandora’s Box? It’s a question that even Le Corbusier would have been hard pressed to answer. After all, he couldn’t even make up his mind about La Maison Blanche. ‘I’ve been ashamed of it,’ he confessed. ‘I’ve hated it!’ Yet try as he might, he couldn’t dismiss it as a youthful folly. ‘At the foot of the wood, in the beech grove, looking at the long range of the Jura,’ he reflected, ‘its rhythm and its spirit are of the Orient.’ Standing here today, 100 years later, the beech trees hide the tower blocks in the valley down below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in