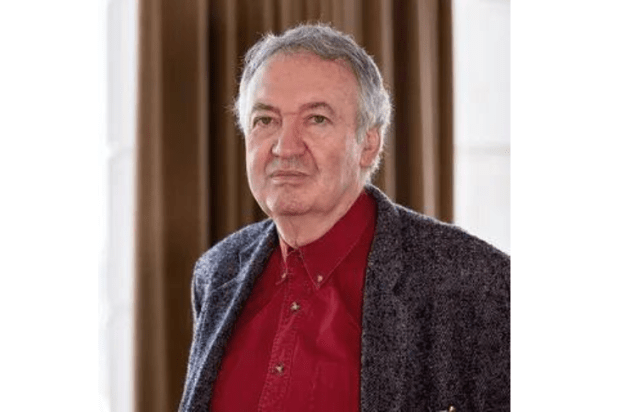

Henry Kissinger, Owen Harries, Samuel Huntington, March 1998

History’s best beginning for a printed obituary was the beginning which Clive James used for his New Yorker obit of Princess Diana. It consisted simply of the word ‘No.’ And as it happens, that very word was my own immediate, instinctive response when former Quadrant editor Lee Shrubb (long since retired but still Sydney-based) told me on the phone that her fellow Sydney resident Owen Harries had died.

No. No, damn it. An Australian intellectual class so wonderfully cultured and historically literate that it could ever afford to lose the wise example and counsel of the Welsh-born, long-American-resident Professor Harries would be an Australia altogether unimaginable outside science-fiction.

Professor Harries (he insisted on my calling him ‘Owen’ when I was disgracefully young, impressionable, and heedless of the honour he thereby did me) wrote no books that revolutionised political thought. He was no James Burnham, no Hannah Arendt, no Russell Kirk, no Raymond Aron, no Isaiah Berlin (though he studied with the last-named).

But he didn’t need to be. The best word for him is that almost untranslatable French noun animateur. Diaghilev, Jean Cocteau, and, yes, Clive James were all animateurs. Although I cannot imagine ballet, French art-house movies, or Japanese quiz-show footage inspiring Owen to any emotion except nausea, he shared much of those men’s action-oriented verve.

With Owen on an editorial committee, hitherto obdurate dialectical antitheses would somehow become Hegelian syntheses. Under his ministrations, local alcoholic Oblomovs keen to avoid any income-generating activity since the last time they attended a John Anderson philosophical lecture, at Sydney University circa 1954, would miraculously acquire an imposing (if temporary) veneer of authorial competence. Perhaps no-one outside the magazine world perceives the almost thaumaturgical gifts involved in extracting grammatical, accurate, orthographically correct prose from the average antipodean pundit before deadlines strike. Owen did it not once but often.

When Owen moved to Washington DC and was made editor of The National Interest in 1985, certain Sydney ill-wishers behaved as if the job had gone to Paul Hogan, or possibly to Strop. They hadn’t known Owen, in his Quadrant role, before 1985. I had. He and his wonderfully charming wife (also Welsh-born), Dorothy, had long been both staunch friends of my parents. They were crucial to my childhood and adolescence in both New South Wales and England. Dorothy was the more conversationally sportive; Owen preferred rationing his interlocutory insights. But when he did remove his pipe and speak, the resultant devastating epigram could almost strip the enamel off a lavatory.

Once, with Owen present, the talk turned to the subject of a Bollinger Bolshevik in Sydney’s east. Fortunately, I never met this Bollinger Bolshevik, whose blend of Third World revolutionist zeal with the sanctimonious manner of a defrocked priest moved Owen to rage. Never can I forget Owen’s disgusted epigram about him: ‘Even his voice has B.O.’

From which it will be obvious that Owen (a Royal Air Force conscript during the Korean War, by the bye) had the virtue often attributed to the most esteemed generals and admirals: a virtue summed up in the military proverb ‘You gave your best to him, because he wanted the best from you.’ Tyrannical? No way. One example alone of Owen’s fundamental unpretentiousness must suffice.

In the 1970s, my parents, my sister, and myself all lived in an Oxfordshire village with – today’s youngsters will learn to their stupefaction – neither Foxtel nor the Internet. Horribly homesick, my father, the philosopher David Stove, desperately craved rugby league results from NSW: results which, to his annoyance, British newspapers and British television nowhere mentioned. What could my father do? He somehow persuaded Owen to make international telephone calls to him from Canberra (bearing in mind the relevant time-zone differences), so that Dad could be apprised of whether Manly had trounced Parramatta that day, or whether Canterbury had vanquished Newtown. This service Owen always performed without complaint.

Others – notably Tom Switzer in the November 2015 American Conservative – have expounded Owen’s activism as (in Tom’s own phrase) ‘dean of the realists.’ These matters adorn the public record and are best dealt with by Tom’s fellow experts.

Yet for me, Owen’s accomplishments will always be the accomplishments of his own needlessly modest self-description: ‘a boy from the Rrrrrrrrrrrhondda Valley.’ How I loved to hear those rrrrrrrrolled Rs of his (and still more of Dorothy’s), undiluted by Stateside employment. How deep was his love of Purcell’s music, a love he shared with Dad. How grateful I was to him for putting me up – indeed, for putting up with me – when, in 1990, a medical crisis afflicting me in DC made a continued stay at my hotel impracticable. How dire his future would have been if first Welsh, then English, university scholarships had not rescued him from coal-mines and probable mesothelioma.

I last saw him in 2016 at a pub on Sydney’s North Shore. Though the flesh was weak, the willing spirit shone through him as from a sword that catches the sunlight. We exchanged memories of Quadrant; of our differences with Bob Santamaria; of my father’s miserable last six months. At the end of our lunch he gave me an inscribed copy of his 2004 Boyer Lectures book: Benign or Imperial?. Always prone to Attlee-type concision, Owen scorned to waste words now. On the flyleaf, he inscribed, in a black-texta cursive unweakened by age, these words: ‘For Rob, who understands.’

There is no compliment I have ever received from others which meant then, and which means now, anything like as much as do those four words from that scholar and gentleman. As Shakespeare should have made Mark Antony say: ‘This was the noblest Welshman of them all.’

Owen Harries, 1930-2020. Welsh-American-Australian scholar and gentleman.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in