‘The New York Times attacked me – they called me a nationalist,’ he said, facing the camera, with a stern look, healthy head of hair and low body-fat percentage while his wife and three young children played Monopoly in the foreground.

‘Got me. Guilty as charged… I love my country, and just like President Trump, I want to secure our borders.’

His name is Blake Masters, and he just won the Republican Primary for the Arizona Senate. At 36, he beat older and more experienced candidate Jim Lamon, and in September will face off against ex-astronaut and establishment Democrat, Mark Kelly. ‘I’m going to win,’ Masters said.

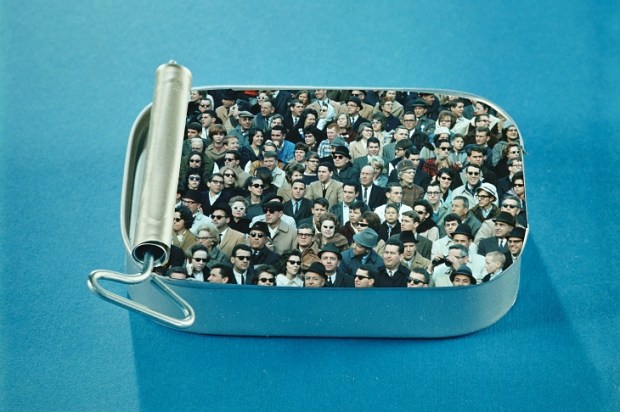

Masters is part of a movement known as the New Right. They are a group of young, ‘post-leftist, heterodox and dissident’ right-wingers who see themselves as ‘counter revolutionaries’ fighting against what they refer to as ‘the regime’ – the neoliberal, globalist world order’. Rather than preserving the status quo – which they’d consider essentially over – they see their role themselves as agents of restoration, building a new path forward.

James Pogue, one of the first journalists to cover the movement in more depth, told Vox recently:

‘Globalisation was sold as if it would make all of our lives better. But largely speaking, it has enriched a very small, well-connected, international, sort of, elite set of schools, elite set of institutions. This trend of “open borders” is pushed forward in the name of progress and liberalism.

‘But actually, what it’s doing is driving down wages and impoverishing people.’

Nate Hochman writes in the National Review:

‘There’s not a lot left to conserve in the contemporary state of things. Conservatism today means radicalism.’

This ‘fractious family of dissenters’ may come to represent a political shift that reaches further, runs deeper, and is more operationally effective than the Trump years (but don’t count him out yet). One that – thanks to its hipster, hyper-cool online following – may quickly spread abroad. Here in Australia, it may be welcomed with open arms.

‘I don’t think for a moment that the LNP has a genuine interest in representing conservatives,’ a friend texted me recently. The Liberal Party, along with mainstream conservative commentators, are ‘facilitating their own irrelevance’ by ignoring the issues that matter most: home ownership, social cohesion, and the family unit.

‘I’m politically homeless,’ he told me. A sentiment that many young people – isolated from home ownership, castigated by Wokeism, burdened with low wages – are feeling, and one which American politics is now beginning to tap into.

There is no New Right/America First playbook, but there are policies that have remained consistent, including stopping illegal immigration, dramatically cutting legal migration, and tackling big tech (including, interestingly, its addictiveness). On a domestic level, Masters wants a median wage increase so people can ‘raise families on one-single-income’ and to bring schools and universities ‘back to reality’. Manufacturing needs to return – ‘jobs, not iPhones, or pill bottles’, and on foreign policy, American families always come first – ‘I don’t care what happens in the Ukraine, frankly.’

From the outside, one key difference to Trump is that the New Right isn’t a one-man army, seeming to be far more organised. To the north in Ohio is JD Vance, the best-selling author of Hillbilly Elegy. He recently won the Republican senate ticket by taking on the ‘community destroying’ effects of globalism. To the south in Florida, there’s Governor Ron DeSantis – whose star is rapidly rising, thanks, in part, to his stance on lockdowns and mandates.

The New York Times put it this way: ‘One way or the other – whether he ever runs for president or not – Ron DeSantis is the new Republican Party.’

Behind the scenes, Curtis Yarvin, a tech-founder turned political theorist – considered by many as the philosophical heft of the group – lends intellectual insight and certainly interesting ideas with meandering Substack articles laden with internet-speak (he claims to have been the first to use the term ‘red pilled’ in a political context).

‘Basically, you’re looking at something that calls itself a democracy, and is actually an oligarchy,’ he told Unherd.

‘The administrative state has practical control over the ceremonial politicians. The politicians you elect are not in charge, so you are not in charge.’

This, he said, is thanks in part to what he calls ‘The Cathedral’: a complex explanation of why most of the media institutes and experts seem to say the exact same thing at the exact same time, despite there being no clear top-down directive.

‘The Cathedral is just a short way to say ‘journalism plus academia’ – in other words, the intellectual institutions at the centres of modern society, just as the Church was the intellectual institution at the centre of medieval society.’

To simplify this, Yarvin’s idea is that the ‘Cathedral’ represents the brain, whereas the deep state – or administrative state – is the body.

‘The brain,’ he reminds us, ‘generally controls the body.’

And then there’s Peter Thiel. Both a major financial backer and controversial figure in his own right, Thiel’s involvement in right-leaning politics – backing Trump and now Masters – draws continued ire from America’s media class.

‘Thiel and Masters are willing to move fast and break things. But instead of disrupting taxi companies or hotels, they’ve got American democracy in their sights,’ wrote Mother Jones.

Thiel’s involvement is arguably less about gaining power and seems more out of fear of what is around the corner. His view is that the globalised world we now live in was arrived at absent-mindedly, expecting no consequences. With no plans for the future, mankind has unwittingly progressed itself into a corner with scarily few exit options. Mildly prophetically, he envisions either a monumental shakeup of globalism and politics, or ‘total war and annihilation’.

‘In every possible future, all of today’s bubbles will burst, and their ideological scaffolding will prove to be but lint in the winds of history…

‘The waning of globalisation in the near future will be a reaction to the excesses of the recent past.’

But his more recent comments have been more hopeful, or, at least, less biblical. ‘I think the tide of globalisation is just going out,’ he said.

‘Politics is becoming more important, it’s becoming more intense, the range of outcomes is becoming greater… we’re in a world in which there’s a bull market in politics that’s getting started.’

Thiel may be bullish on this brand of politics because, in people like Masters and the New Right, he sees a chance to arrest American decline. Many others hope he is right.

If these figures are anything to go by, the New Right is young, energised, digitally shrewd, highly intelligent, and not afraid to court controversy. They see globalism as a corrosive force on society, mainstream media outlets as elite self-serving institutions, and America as a nation in spiritual and economic decline.

‘It feels like everything is coming apart at the seams. If we don’t right this ship, America is gone,’ said Masters.

Many would laugh and say that Australia isn’t quite there yet. But in some ways, we’re far worse. After nine years of a ‘conservative’ government, we now have extraordinary levels of debt, suffered some ‘the worst violations of human rights in Australia’s history’, the highest house prices we’ve ever seen, a system dependent on mass migration, and a prevailing sense of dread.

As Rowan Dean put it, ‘The legacy of Scott Morrison’, and, to many, the LNP, ‘was an absolute joke.’

How did it get to this point? Nick Cater wrote recently in The Australian that conservatives are ‘lost’.

‘Conservatism has become so confused it is hardly capable of conserving anything at all.’

But surprisingly, to Cater, Trump was someone, ‘Who, for all his strengths, was hardly Reagan, nor anything approaching what might have been classed as conservative a decade ago.’

Maurice Newman, writing in Flat White, also acknowledges the dark turning-point the Western world has found itself in. He concluded by asking; ‘Do we have the courage to turn back?’

This, the New Right would argue, is the wrong way of looking at it. The idea of ‘returning to our roots’ or ‘turning back’ – though noble and true to the conservative instinct – doesn’t match the needs of the day. The Right today cannot just be the party for ‘less tax, more globalism’. Conservatives are fighting a cultural, economic, and spiritual civil war using Reagan-era weapons. They’re losing.

What Vance, Masters, and others on the New Right do is voice what many on the right-wing are thinking. First, the neoliberal world order that promised to make our lives better did the exact opposite, and second, that a globalist type of conservatism is indictable for this decline. Reagan, Howard, and Menzies did their job, but we need to look to the future. This will take radical changes in talent, ideas, and systems of government. The stakes are simply too high.

Vance put it another way:

‘We’re in a late republican period. If we’re going to push back against it, we’re going to have to get pretty wild, and pretty far out there, and go in directions that a lot of conservatives are uncomfortable with.’

It’s time to get uncomfortable.

The author invites you to send hate mail or questions to jordanhenryknight@gmail.com

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in